How to Feed Your Characters: The Food Timeline

Writing about some hungry characters? In a time or place very different from your own? The Food Timeline might just save your bacon.

Founded by New Jersey-based reference librarian, Lynne Olver, FT is a free, open-access website and research service devoted to the history of all things culinary.

I interviewed Ms. Olver to find out more about this remarkable personal project—and to get some advice about writing food-related scenes in historically and culturally accurate ways.

PSHARES: How did you get the idea for the Food Timeline website?

LO: The website was inspired by James Trager’s The Food Chronology. This epic reference book chronicles key food events from prehistory to the 20th century. I was intrigued by the concept. As a reference librarian working in a public library, I encountered food history questions on a regular basis.

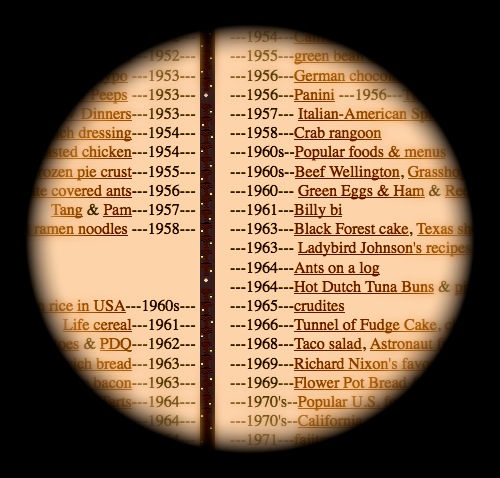

When the Food Timeline debuted in March 1999, it offered a single page with links to vetted research sources. As time progressed, additional links, original content, and topical pages were added. Today’s site has 50 pages. Most of the content is researched, transcribed, HTML coded and uploaded by the editor (me). Food Timeline entries are selected based on questions frequently asked by our patrons. It is a work-in-progress and a labor of love.

PSHARES: How many books are there in FT’s collection?

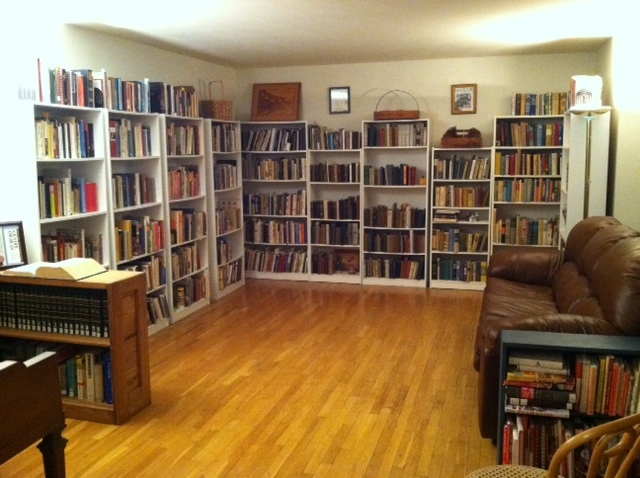

LO: We have over 2,000 titles. They’re grouped in these categories: historical cookbooks (collection is global, focus is English language and USA); culinary history texts (scholarly annotations); food “biographies” (including five books on the history of hamburgers); restaurant collection (cookbooks published by famous restaurants, restaurant procedure manuals); presidential cookbooks, wine/beer/cocktail guides and catalogs; historical pricing and statistics; and food company histories. We also own approximately 300 corporate cooking booklets, dating from the 1890s to the 1970s.

PSHARES: Where are all these materials stored?

LO: FT Library is housed in my living room. It also has a piano.

PSHARES: What other resources do you use in your research?

LO: The Internet provides ready access to more material each day. This has revolutionized the way all of us access information. We regularly tap historic newspapers (Library of Congress, Newspaper Archives, ProQuest Historic, Factiva), searchable digital cookbook collections (Michigan State University’s Feeding America is a gold mine), historic menus (Los Angeles Public Library, New York Public Library), and major culinary libraries for titles and digitized copies (Harvard’s Schlesinger Library, Culinary Institute of America). Google Books, HathiTrust and Internet Archives offer keyword access to historical cookbooks. Duke University’s Scriptorium offers access to food company advertising materials.

One caveat about digitized sources: in many cases, there are many different editions of cookbooks, and the Internet does not offer all editions of every book. It is easy to fall into the habit of assuming one edition is the same as another, but editors make changes based on current public demand.

PSHARES: You offer a free Q & A service, with all responses reported back via email within 24 hours. Amazing! How many questions have you answered?

LO: We’ve answered 25,000 questions for 31 million readers from March 1999-June 2013. A complete question catalog is available here. What you see online is the tip of the culinary iceberg. Content is revised, added, and corrected daily.

PSHARES: What are some popular kinds of questions you get?

LO: We welcome questions from everyone all over the globe, from grade school children writing state reports to European chefs searching for specific historic recipes. Culinary students, K-12 teachers, historic reenactors, party planners, scholars and curious people are regular patrons. During the holidays, we are inundated by readers searching for lost family recipes. We do our best to help in the recipe recovery effort. What a joy it is to have grandma’s special lemon pie on the table again.

PSHARES: Do any writers use your services?

LO: The Food Timeline is regularly tapped by writers, editors, fact checkers, reporters, and media producers. Writers generally fall into two categories: (1) Cookbook authors requesting historical headnotes/breakout boxes to accompany recipes (2) Historical novelists asking what kind of food would be typically consumed by their characters.

We applaud these writers’ commitment to historical accuracy. It’s challenging enough to write from personal experience. Developing characters and telling a story set in specific historical context must be one of the most difficult projects a writer can pursue. We are happy to help.

PSHARES: What are some things fiction writers need to keep in mind when “feeding” their characters?

LO: What people eat in all times and places depends upon who they are (ethnic/religious heritage), where they live (urban centers, rural outposts), and economic status (wealthy people have more choices). The role of food in a specific literary work can be primary (Oliver Twist/Dickens; Babette’s Feast/Dineson; The Jungle/Sinclair), secondary (dining or market scenes/Chekov, Dostoyevsky) or tertiary (general historical filler). The level of food detail is driven by the purpose.

PSHARES: Would you have time to help out a few fiction writers out right now?

LO: We are happy to address their specific questions in a general way.

PSHARES: Our first question comes from Clifford Garstang, who is working on a novel set in Singapore in 1915-16. His characters are British civil servants and he’s writing a scenes where they’re eating breakfast and/or tea. What should he “serve” them?

LO: The British Empire bequeathed future generations with detailed culinary chronicles for nationals stationed abroad. English families stationed in 19th century India and Australia, for example, wrote detailed household instruction manuals covering all aspects of outpost household protocol. These included common food stuffs, “foreign foods,” instructions for servants, adapted cooking methods and general recipes. What these books confirm is the British did their utmost best to retain their cuisine wherever they were.

A proper British tea in Singapore would have the same arrangements as any other point of the globe at that time. Biscuits and finger sandwiches. Recommended reading: Food Culture in Colonial Asia: A Taste of Empire by Cecilia Leong Salobir. Is this regular afternoon tea or high tea? Differences here.

PSHARES: Our next question comes from fellow Ploughshares blogger, Rebecca Meacham. She’s working on a novel set in Door County, Wisconsin in 1871:

“A woman is cooking breakfast while her family sleeps. She’s in a good mood for the first time in months, and she wants to make something to share this good mood with her family (there are two little kids and her husband). What is she making? Ideally, it would be something with a few more steps than “fried eggs.”

LO: Local community cookbooks and newspapers are the best reflections of what people ate in these situations. Identify cookbooks with these tools: (1) American Cookery Books 1742-1860 by Lowenstein and Culinary Americana: 100 Years of Cookbooks Published in the United States from 1860 through 1960 by Brown. Some of the cookbooks these two volumes list may be available online. Others have been reprinted and can be ordered via Amazon.

Recipes did not change radically from decade to decade before WWII. A cookbook published 20 years on either side of your target date is generally okay. The closest book in FT library is the Capital City Cook Book/Grace Church Guild, Madison WI (paperback reprint). Most older cookbooks do not offer menus. According to this book, the happy breakfast maker could make her eggs thusly: baked, curried, French, Fried boiled, Mexican, omelets (several kinds), scrambled or stuffed. She can serve biscuits, muffins pancakes, and waffles. In the late 19th century breakfasts often included a meat choice: bacon, steak, ham.

Ideally? This character would be making her family’s favorite foods. A small slice of leftover pie might be a special treat for the children. Something to ponder: in this period seasons played a key role in food availability. Fresh strawberries paired with waffles could only happen in the early summer. Not like today.

PSHARES: And our last question comes from playwright M.E.H. Lewis: She’s working on a play set in present-day Argentina and her characters are a middle-class family. What could she “serve” them for a regular family dinner?

LO: Present-day foods are relatively easy to research because we have ready access to a wealth of country-specific cookbooks, travel books (Lonely Planet series is good for what to expect for food), culinary tours, and country travel bureaus. Caveat: Argentina, like the USA is a very large country with many different culinary legacies. Germans settlers probably eat different foods from Spanish, Portuguese, and indigenous families. Flip this question for context: “What does an “average middle class family eat in the USA today?” There is no right or wrong answer.

Have a question of your own? Ask! Contact foodtimeline@aol.com. In a browsing mood? Visit the Food Timeline’s website, or take in some tantalizing visuals on FT’s Pinterest page. And for fascinating daily culinary history tidbits, follow Lynne on Twitter.