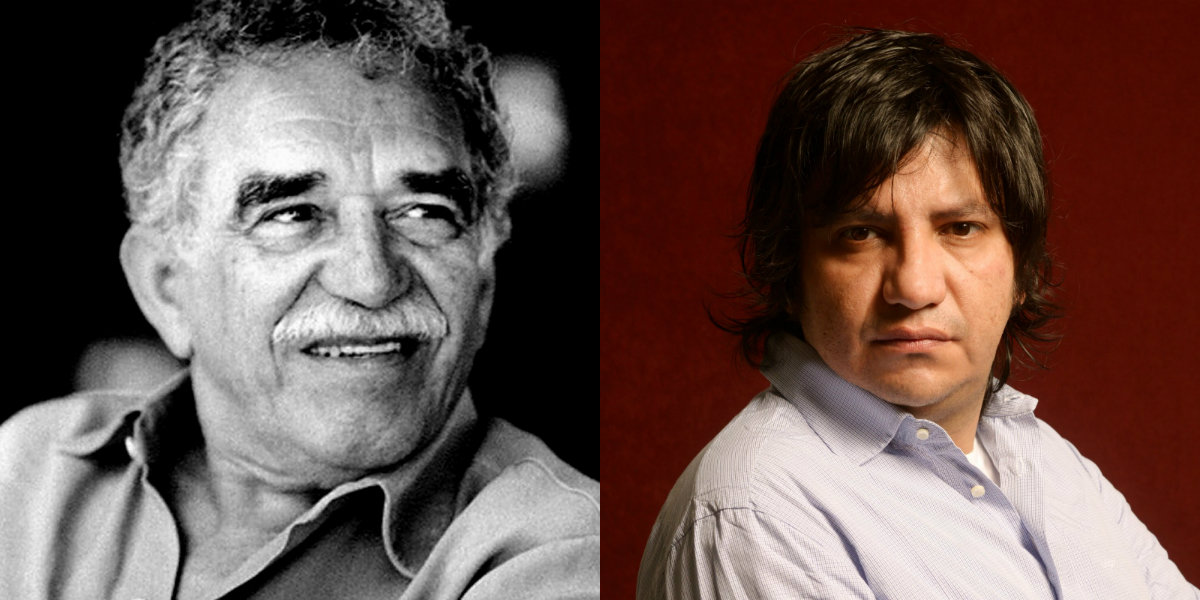

Literary Enemies: Gabriel García Márquez vs. Alejandro Zambra

Literary Enemies: Gabriel García Márquez vs. Alejandro Zambra

Disclaimer: García Márquez has no enemies but the F.B.I.

A few weeks ago I went to a panel at the National Book Festival that featured Alejandro Zambra, a Chilean writer I like a lot.[1] (Yes, I started reading him because of the James Wood piece about him in The New Yorker; yes, I recommend that you do the same.) The panel had initially been conceived as a tribute to Juan Rulfo, whose novel Pedro Páramo turns sixty this year, but the Rulfo family did not comply in some way that was left vague but definitely involved money, and so instead the panel was about Time.

No one knew what to make of this, including the authors. They made a lot of comments about Rulfo anyway, and talked about history and archives and such. They did the best they could. I spent most of the time trying to make eye contact with Zambra in order to tell him telepathically that his newly translated book, My Documents, is one of the best story collections I’ve read all year, but I don’t think he got the message. He was too busy fending off questions about Gabriel García Márquez.

To be clear, this panel had nothing to do with García Márquez. None of the authors mentioned García Márquez. But somehow, when the audience questions began, there he was, hovering over us like the ghost of Melquíades. Which was fine, I guess, until somebody stood up and asked the four Latin American writers on stage,

“Do you think creativity is just gone from Latin American writing entirely now that García Márquez is dead? I mean, do you think anyone will ever have an original idea again? And if not, why don’t you guys just collaborate?”

I wish I were making this up, and I wish I could tell you that the writers had not responded to this question with perfect courtesy, as if it were a reasonable thing to ask. I hope they laughed about it later. I hope they were surprised by the question, but I highly doubt it. I wasn’t. I have long thought that English-language reading of Latin American fiction suffers from a severe case of García Márquez Disease, and this was more proof.

I love García Márquez. He is a brilliant writer, and a brilliantly translated one (credit where credit is due). His work is massively important. It is also massively imitated. And somehow it has happened that imitation García Márquez sells well in the United States, a phenomenon about which Daniel Peña has already written on this blog. It gets taught. English-language readers start to expect mysterious trails of blood, and jungles, and incest, all of which is fine. I like a good trail of blood as much as the next girl. My problem is with the expectation. My problem is with the blurb on the back of my copy of My Documents that calls it “a new Latin American literature.”

My Documents is a very good book. It is funny and well written and innovative. It is packed with literary references in a way that I find reminiscent of both Roberto Bolaño and Valeria Luiselli, to whom Zambra’s story “I Smoked Very Well” is dedicated, along with Álvaro Enrigue. (Zambra, meanwhile, gets a mention in Luiselli’s new novel, The Story of My Teeth.) Several of its stories, most of all “National Institute,” have alienated young protagonists who remind me of the main character in Alberto Fuguet’s Bad Vibes, another Chilean book that I highly recommend. What I’m saying is, My Documents is not a new Latin American literature. It’s just not magical realism.

I’m not sure there’s a name for the kind of realism that Zambra writes. It’s cerebral, as I mentioned before, and sometimes skeletal, and a bit oddball. It’s not apolitical, though his study of Chilean politics is sidelong and often done through a child’s eyes, as in “National Institute” or in his novel Ways of Going Home, in which “a Communist was someone who read the newspaper and silently bore the mockery of others.” Ways of Going Home might be about the fallout of the Pinochet regime, and Zambra’s narrator may later describe the dictator as a son of a bitch and a murderer, but Pinochet first appears like as schoolyard graffiti, with messages including “bawdy sayings, phrases for or against [Chilean soccer team] Colo-Colo, or for or against Pinochet. One phrase I found especially funny: Pinochet sucks dick.”

Zambra treats romance much the same way as politics. His novella Bonsai speeds through a love affair like nobody’s business, which it isn’t, I suppose. He instills the book with a sense of loneliness and gloom that echoes forward from the first paragraph: “In the end she dies and he remains alone, although in truth he was alone some years before her death, Emilia’s death. … In the end Emilia dies and Julio does not die. The rest is literature:” And no, that colon is not a typo. Perhaps I should call Zambra’s work literary realism.

Or else I could say it’s McOndo, which is a literary movement that Alberto Fuguet proposed eighteen years ago in his essay “I Am Not A Magical Realist!” Enough of the jungles and incest, Fuguet says. Big Mama is buried and the handsomest drowned man in the world has, you know, drowned. Time to write about contemporary Latin America. Bring on the novels set in malls and airports, the short stories about the life of a Chilean computer. That last isn’t from Fuguet’s manifesto. It’s “Memories of a Personal Computer,” the fifth story in My Documents, and I highly recommend that you give it a try. It may not be a new Latin American literature, but I promise it’s an original idea.

[1] The other writers were Álvaro Enrigue, Cristina Rivera Garza, and María José Navia, about whom all you need to know for the purpose of this essay is that they are not magical realists.