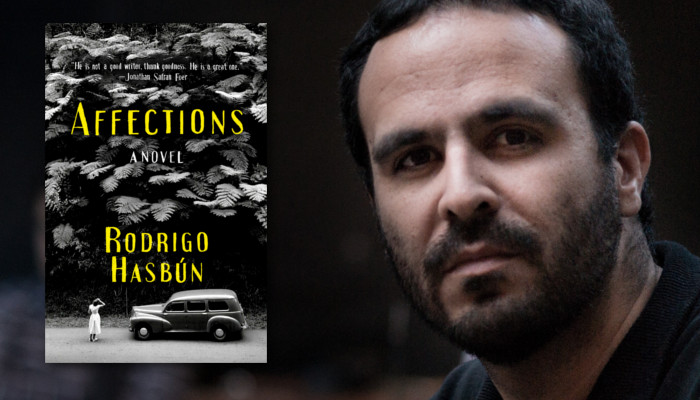

Rodrigo Hasbún’s Affections: Identity in a Post-Truth Era

Lately, I’ve been thinking a lot about the decentering of certain words in this so-called “post-truth era.” Most recently, this has led me on my quest in finding the exact center of identity: the contemporary definition, not the dictionary one, and not necessarily my own identity either (though that too). It’s a fact that definitions change. Language evolves. But identity has done quite the opposite. It’s become less dynamic, less nuanced with use.

You hear identity and you instantly think politics in the next breath. Such is the radical centering of certain words so pervasive in the public consciousness that they become sterilized. But sometimes the opposite is true (think literally, think mortified). What does identity exactly mean anymore? And does the way we think about it shape the way we think of ourselves in relation to each other?

It’s perhaps because of the invisible currents that inform “post-truth” that I’m finding myself reading and rereading Rodrigo Hasbún’s Affections, which is hands down my favorite book of 2017.

Hasbún’s novel, translated into English by Sophie Hughes, explores the concept of identity as a thing trapped within the two-dimensional plane of temporality: Left-to-right. Beginning-to-end. Things happen, epiphanies are had, and those epiphanies change us. Hasbún decenters what I suspect is the way most of us approach narrative—that a story can’t be a story in the “vulgar sense of the word” as Henry James would put it (an anecdote), but a character must change from the beginning of the story to the end of the story. This obviously happens too in Affections, but Hasbún’s characters exist within the liminal spaces of each moment as well, each character’s identity constantly in flux within scene. And this, I think, is what makes his novel so haunting, so good, and so particularly timely.

As the definition of identity is malleable, Hasbún shows us just how many ways that word can bend. And this makes his novel less about the narrative arc of the novel than the narrative prism whose characters make up the facets which converge to fracture the so-called “truth,” that light as filtered through the lives of the characters that inhabit his novel: Hans Ertl (a Nazi cameraman turned political escapee, formerly under the direction of Leni Riefenstahl), his wife, and his daughter’s Monika, Heidi, and Trixi who move to La Paz, Bolivia in the immediate aftermath of the collapse of Nazi Germany.

The novel is made up of twelve vignettes, the first of which opens with Ertl proclaiming that alpinism had become too technical and that, “[…] the important things were being forgotten, that he wasn’t going to climb anymore.” This scene, narrated by Heidi, launches into Hans’ proclamation that he’s pivoting toward a new adventure: “[…] he would soon be leaving in search of Paitití, an ancient Inca city buried deep in the middle of the Amazon rainforest.”

It’s not long after this scene that the novel becomes less about finding Paitití than about the dissolution of the Ertl family in the wake of their failure to find the lost city, and ultimately, the fraught relationships the sisters have with each other after their mother’s death and their father’s retreat into nature. Paitití is the catalyst, though not necessarily the cause, of this dissolution. But the seeds of the novel bloom from this opening vignette. We get the keen observational eye of Heidi, the loneliness of Trixi, the backstory that will eventually turn to tragic love, and the radicalization of Monika who later who becomes one of Bolivia’s more notable Marxist Guerillas for having assassinated Bolivia’s ambassador to Germany who was responsible for killing and dismembering Che Guevara.

The broad sketches of the true-life Ertl family are interesting enough, but what I love about Hasbún’s writing here is that his tight scope on character is less about the things these people do than the reasons informing why they do them in the first place. With this in mind, you get the sense that each character is acting and reacting not necessarily to each other, but according to the demands of their own identity—as informed by blood, anxiety, grief, and guilt among other things—constantly in flux.

The end result is that the “truth”—whatever that is—comes out as a fractured thing. Memory is fallible. But so, too, are the possibilities with which any one character might view themselves or relate to each other.

I’d never thought of identity in this way. This level of disconnect (as informed by the limits and multitudes of a person’s grasp of their own identity) is a fascinating source of conflict and the driving force behind Affections. And it’s also the thing that makes these twelve vignettes feel cohesive, as disparate in voice and temporality as they are. To that end, vignette doesn’t feel like the right word here. Vignette feels too close to anecdote and It’s obvious that the sum of these passages is something more than a string of vignettes. The entirety of this book feels like something more than merely a novel. Affections is something beyond.

It should be said that Hasbún’s novel isn’t speaking directly toward the idea of “post-truth,” but I can’t help but read it with that lens. Identity has everything to do with post-truth. And for many reasons, Affections might be the novel America needs. At the very least, it’s the novel I need. A novel that pushes beyond the common concept of “the novel,” but also the novel that breaks open the common concept of what it means to be a person, what it means to to know one’s identity.