The Dangerous Age’s Repudiation of the Marriage Plot

In Flash Count Diary, her 2019 book on menopause, Darcy Steinke cites the observations of Katha Pollitt and Carolyn Heilbrun on the “storylessness” of women—specifically, our confinement in stories to “erotic narratives” that generally lead to the altar. If these are the only narratives available to women, notes Steinke, then menopause marks the end of the tale: “I have felt that my story was over, that nothing more would happen to me,” she writes. This plight for a woman in mid-life is evident in the enactment and repudiation of the marriage plot in the 1910 novel The Dangerous Age, by Danish author Karin Michaëlis.

The novel’s first repudiation of the marriage plot is its beginning with a divorce: that of Elsie Lindtner, the narrator, from Richard, her husband of 22 years. In a letter to her cousin Lillie, Elsie writes that there is “no special reason” for the divorce—no scandal, no affair on either side. Indeed, she claims that she and Richard “have got on as well as any two people of opposite sex ever can do” and have never spoken in anger to each other. She continues:

But one day the impulse—or whatever you like to call it—took possession of me that I must live alone—quite alone and all to myself. Call it an absurd idea, an impossible fancy; call it hysteria—which perhaps it is—I must get right away from everybody and everything. It is a blow to Richard, but I hope he will soon get over it. In the long run his factory will make up for my loss.

Elsie’s idea that her ex should find consolation in his business for the loss of his wife, like her claim that she and her husband never expressed any anger to each other, suggests that there was little love or intimacy in the marriage. Later, in her journal, she confesses that in fact she and her husband often “gave way to each other with a consideration masking an annoyance that rankled more than a violent quarrel would have done,” and that the “bargain” of their marriage, in which they appeared “like an ideal couple,” was simply: “My person for his money.”

Making such a bargain, Elsie later reveals, was her goal since a schoolmate said to her, “Of course, a prince will marry you, for you are the prettiest girl here.” At the time, she told the family maid what her schoolmate had said, and when the maid replied, “That’s true enough . . . A pretty face is worth a pocketful of gold,” she asked, “Can one sell a pretty face, then?” “Yes, child, to the highest bidder,” said the maid. With this new understanding of the value of her appearance, Elsie determined to maintain it: she avoided the sun, sweets, and wild games that might get her injured; she slept in gloves, brushed her hair for hours, and, when a mirror was moved into her bedroom, practiced her smile and other expressions. Next, she schemed to marry the chief magistrate, Herr von Brincken, a much older widower who lived in a “white building in the style of a palace.” When von Brincken realized, however, that Elsie actually found him physically repugnant (which Elsie herself appears not to have understood), he broke off their engagement; afterward, she met Richard in Paris and, having learned from her first engagement, pretended to love him well enough to get him to marry her.

Elsie’s grand success in becoming a desirable object in her youth explains her sudden need in middle age not just to divorce her husband, but to leave society altogether and live alone (with two servants) in a villa on an unnamed, inhospitable, forested island. In society, all that she can be is a thing to look at; for twenty years, she writes, “I . . . have never even dressed the salad without at least one pair of eyes watching me toss the lettuce as though I was performing some wonderful Indian conjuring trick.” For a woman to be anything other than a beautiful object is to be worse than irrelevant; she writes: “Their youth only counts so long as their complexions remain clear and their figures slim. Otherwise they are exposed to cruel mockery. A woman who tries late in life to make good her claim to existence, is regarded with contempt. For her there is neither shelter nor sympathy.” In lieu of contempt, Elsie chooses absence.

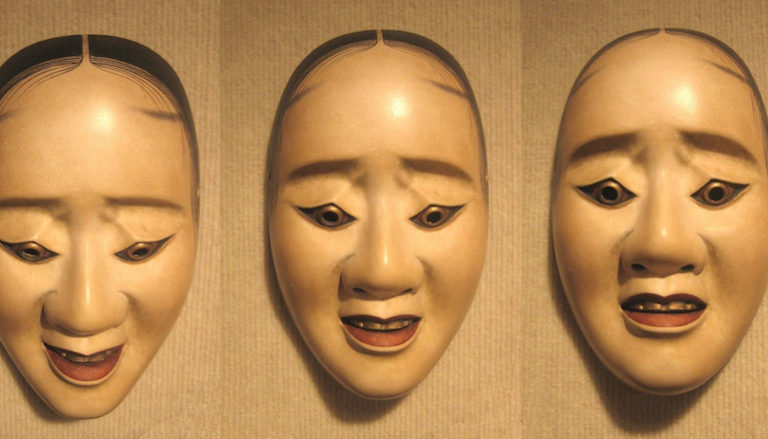

In abandoning society, Elsie also chooses her inner life, which she had quashed for decades—in part, she implies, to maintain her necessary beauty. As she once told a group of women friends, “However much I wanted to cry, I only permitted myself the luxury about once in two years. I think my complexion is a conclusive proof that my words were sincere.” More significantly, she kept her inner life hidden, unexplored, because she regards it as dangerous, or a kind of madness—a common view, it seems. She quotes a letter from Agatha Ussing, a friend who was sent to an asylum during her change of life: “If men suspected what took place in a woman’s inner life after forty, they would avoid us like the plague, or knock us on the head like mad dogs.” Even admitting this much about one’s inner life, Elsie claims, is too much; she writes that Agatha “ought to have kept it to herself instead of posting it up on the walls of her house. It was quite sufficient as a proof of her insanity.”

The inadmissible thoughts that Elsie includes in her diary and in letters to members of her circle in Copenhagen reveal simply that women are neither so faithful nor so virtuous as is expected or believed. Her letters in particular are blunt and impolite. To her friend Magda Wellman, a widowed mother who engages in not-so-secret love affair after love affair, she writes: “A woman of your temperament ought never to bind herself by marriage to any man, and is certainly not fit to have children. You were intended—do not take the words as an insult—to lead the life of a fille de joie. The term sounds ugly—but I know no other that is equally applicable.” To the husband of her cousin Lille, who has confessed that she loves another man, she writes that Lille had been happy insofar as she “willed to be happy” while “in the depths of her heart—so deeply buried that perhaps it never rose to the surface even in the form of a dream—lay that secret something”—a longing to be understood. She concludes: “You must do what you please . . . . but I am very fond of Lillie, and if you abandon her in this cruel and clumsy way, I shall have her to live with me here, and I shall do my best to console her for the loss of an ungrateful husband and a pack of stupid, indifferent children.”

Meanwhile, Elsie longs for Joergen Malthe, a younger man who loved her and is the architect who designed her villa without knowing that she intended to live in it. And so her story does not entirely evade the marriage plot—after all, as Steinke points out, a divorce is a way to make a new erotic narrative possible. Elsie’s thoughts return again and again to Malthe in a profusion of contradictions: she waits for him to write to her; she refuses to read and eventually burns the letter he sends; her love for him is eternal and sacred; she could never possibly marry him. In the end, she sends him a long letter, confessing, “You are the only man I ever loved. And now, by means of this letter, I am digging a fathomless pit between us. I am not the woman you thought me; and my true self you could never love.” Malthe responds to the letter with what turns out to be a brief visit, thus substantiating Elsie’s view that to be known is to be unloved. Or, perhaps he rejects her because her beauty has faded—the text does not make clear why he no longer loves her. Either way, the satisfactory conclusion of a marriage plot, in this story at least, is not available to a woman who chooses truth over beauty. In fact, when she makes a bid for reconciliation with Richard, Elsie discovers that she has no recourse in marriage whatsoever, even a merely tolerable one; he is already engaged to be married again to a nineteen-year-old.

Another type of story is subsumed in the story of Elsie’s disappointed love, though: the story of a possible awakening. She calls her villa a “living grave” and predicts that “before long I shall have dropped out of memory like one long dead.” But in truth, she had always been like a dead person; at school she was “a poor automaton,” dead to the beauties of nature, and as a woman who rarely cried, she was like “deserts which never know the refreshment of dew or rain.” On the island, rather than fade away, she comes alive, discovering pleasure in walking in the forest, bathing in the sea, and stargazing: “I drank in the sky like a plant that is almost dead for want of moisture. And while I drank it in, I was conscious of a sensation hitherto unknown to me. For the first time in my life I was aware of the existence of my soul . . . . What matter that I am growing old? What matter that I have missed the best in life?” Indeed, women need not shape their lives according to the pursuit of men; Heilbrun, Pollitt, and Steinke assert that what they need are quests. And so in addition to her bold and ungracious letters and her discovery of her soul, one satisfaction of Elsie’s story is that it ends with another departure, a potential quest: a trip around the world with Jeanne, her housemaid.

This piece was originally published on March 30, 2021.