The Meaning of Home

As our year of interminable stay-at-home orders continues, it makes for interesting contrast to consider the plight of those for whom returning home is not an option. In her 2016 memoir, Coming Home to Tibet: A Memoir of Love, Loss, and Belonging, poet and writer Tsering Wangmo Dhompa travels to Tibet after a lifetime away following her mother’s sudden death in a car accident. She finds there a place she has often heard of but never seen, a place where past and present, east and west, family and country all converge. As a refugee, Dhompa has lived in Nepal, India, and San Francisco, but it is her return to Tibet that leads her to consider what home means to an exile—it is the center of loss, rediscovery, and reclamation.

Dhompa’s memoir opens with the death of her mother, but their story really begins much earlier, in 1958, with China’s invasion of Tibet. It is this act of violence that sets in motion the loss of home that so deeply permeates Dhompa’s experience and writing. Dhompa tells of how the Chinese invaded and “purported to liberate Tibetans from imperialists and old feudal systems . . . [but] to achieve this liberation was to annihilate the old thoughts and waves of the people.” Chinese liberation meant dividing herding communities, planting wheat instead of barley, and imprisoning political enemies, all of which resulted in mass starvation and deaths, a fundamental destruction of people and culture. To this day, Tibetans “still do not understand why the Chinese, total strangers to them, had come all the way to Dhompa to make them suffer,” but come they did and the Tibetan people suffered. Throughout her memoir, Dhompa returns many times to the actions of the Chinese, showing the loss of home to be a primal wound that she and her fellow Tibetans continue to grapple with. It is an inherited grief still felt by those like Dhompa’s mother who were able to flee, and those like Dhompa who never knew Tibet themselves.

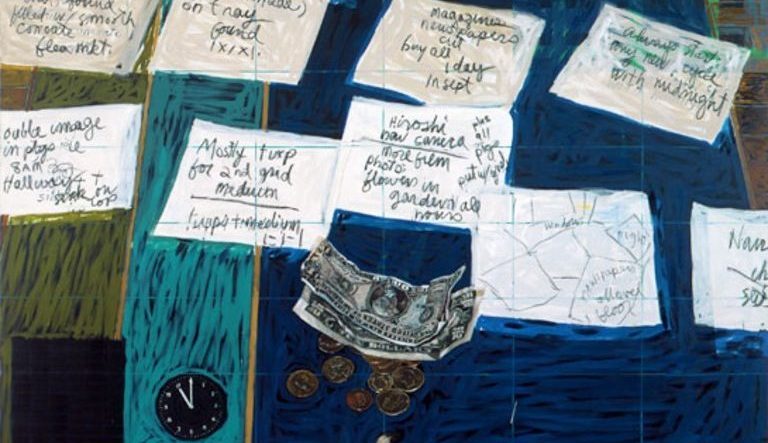

Growing up, Dhompa is naturally curious about Tibet, but her questions yield no easy answers. “Mother was frugal with her references to her father and mother,” she says, “and when she did speak of them she would rush through the stories as though to linger would cause her grief.” When Dhompa “persisted in seeking details of their appearances, she would say they each had one nose, two eyes, and one mouth.” Other times, Dhompa is treated to accounts of how “the flowers in Tibet were always taller, more fragrant and vivid . . . that over time served to create an idea of her fatherland, phayul, as a riotous garden.” These descriptions, with their elegiac and worshipful quality, are indicative of Dhompa’s mother’s attempts to come to terms with her loss. Avoidance, humor, and mythologizing are all present, but over time these tales serve to both preserve and distort Tibet. The homeland becomes a place of forgetting and fantasy, no longer a real place in which people live. This, too, is a loss, as those who left lose touch with what their homeland actually was, replacing it with the stories they have available.

When Dhompa is twelve, however, Tibet briefly becomes real again when “mother received news that . . . her family in Tibet was alive!” For many years, Dhompa’s mother had not known if her relatives were alive or dead, but now Dhompa “was asked to memorize the names of people I was going to love: two aunts, one uncle, twelve first cousins, and my mother’s four cousins. I never thought to question Mother . . . I loved them because I loved her.” In this memory, Dhompa offers a beautiful sentiment about family that is only made stronger when she reveals that a week later she and her mother relocated from Dharamshala to Kathmandu “because [Dhompa’s mother] longed to be physically closer to Tibet.” To move so quickly is impressive, and there can be no greater sign of their longing for home than the comfort received from a mere reduction in distance between oneself and one’s family. There may be no chance of seeing those left behind, but to be closer to them is its own kind of return.

Many years later, when Dhompa does visit Tibet, she once again uses physical proximity to ease a spiritual malaise. Her mother may be gone, but some part of her still exists in her homeland. Dhompa’s Nepalese passport grants her passage into Tibet, and she is able to visit her aunt Tashi, her mother’s sister, and a host of other relatives and friends. With them, she finds the warmth of family and home; knowing the land itself, that riotous garden, phayul, is also a moving experience. Upon arrival, Dhompa feels “it takes my entire body to see this land, and still, there is more.” At times, she and Tashi go out into the land and “lie on our backs. The drama of the sky unfurls above us . . . perhaps it is my nostalgia for this place that gives the sky such grandness. I view the sky as though it belongs only to this location. In this, I am completely unreasonable.” Dhompa’s poetic sense is clear, and she brings to life how going home can feel like learning the sky anew. At the same time, she feels, “I am heartbroken thinking of the future when I will not be here and when this place, too, will be something else.” Even in moments of connection and peace, the Chinese threat is present. This, somehow, is home as well.

There are parts of Tibet that remain relatively untouched. During Dhompa’s stay, she also encounters the nomads of rural Tibet, including getting to know Yungyang, a nomad and her mother’s former maid and playmate, and discovers that Yungyang “has not bathed for a long, long time; nor has she washed her face or brushed her short hair. She cannot say for how long but guesses it could be many decades. She pauses and says perhaps she has never washed—ever!” This depiction is blissfully absent any sense of the romantic pastoral and gives what can only be considered a rare glimpse of life in rural Tibet. In turn, Yungyang and her kin “watch [Dhompa] indulgently as [she] washes . . . they think it is a ridiculous and unnecessary habit.” This culture clash emerges with just the right balance of humor and poignancy, revealing that some of Tibet’s traditional ways remain and may prove resistant to change.

Tibet’s future seems to hang on these elements—the land itself, the Chinese invasion, whether change will come. As Dhompa fields these tensions herself, she also seeks out her family’s perspective, especially that of her uncle Ashang. “At seventy-six, Ashang is my oldest relative in Tibet. He is also one of the oldest lamas alive in our region,” and his life has been deeply impacted by the Chinese invasion. Dhompa learns that “he was on the brink of leading the monastery at nineteen [when] he was named a criminal, and taken to prison. He was released after decades of incarceration, an old man with a head and heart full of sorrow.” His story is one of many, but he is perhaps uniquely positioned to speak on the changes that have come to Tibet. He feels that “‘they are already Chinese, those young Tibetans.’ He insists young Tibetans are different from him. He fears Tibet will change.” In this fear lurks the possibility that there are many ways to lose a home, and that Dhompa may have returned to a Tibet that is no longer quite itself and may never be again.

When pressed further though, Ashang reveals he also believes that “Tibetans are unique because we value the practice of Buddhism . . . we are reminded that nobody is free from suffering.” Although Dhompa protests this view—“how can we free our country with our propensity to accept even macabre injustices as outcomes of our own karma?” she asks—but she also recognizes that such an outlook may ultimately define Tibet’s resistance and resilience. Ultimately, she says, “what are prayers when held against the progress promised by China. But I say this with profound admiration, for there is great strength in believing that things will eventually right themselves. Because they must.” In such moments, Tibet emerges as a home for Dhompa, defined, as it is for so many of us, as a place of both endurance and hope.

This piece was originally published on September 2, 2020.