White Like Me

When you have a gun pointed at you, there’s an odd calm that washes over. Time slows and your movements become languid; all you can do is pay attention to the black eye of the barrel as it stares at you. You become oddly aware of your body: your heartbeat, where your fingers and toes are. You stand still, and in the first few seconds your brain’s too slow or maybe you’re too stupid to be afraid, not fully grasping that the holder of the weapon is just one sneeze away from their trigger finger applying the five pounds of pressure required to make sure you need a closed casket. Five pounds of pressure away from turning bits of your cranium and grey matter into shrapnel smeared against the siding of the shooter’s brick home, right under their car port, ribbons of crimson dripping down their slate gray pavement. I was locked in this memory in 2014, when Ferguson was in flames and I was in my dorm in the throes of writer’s block.

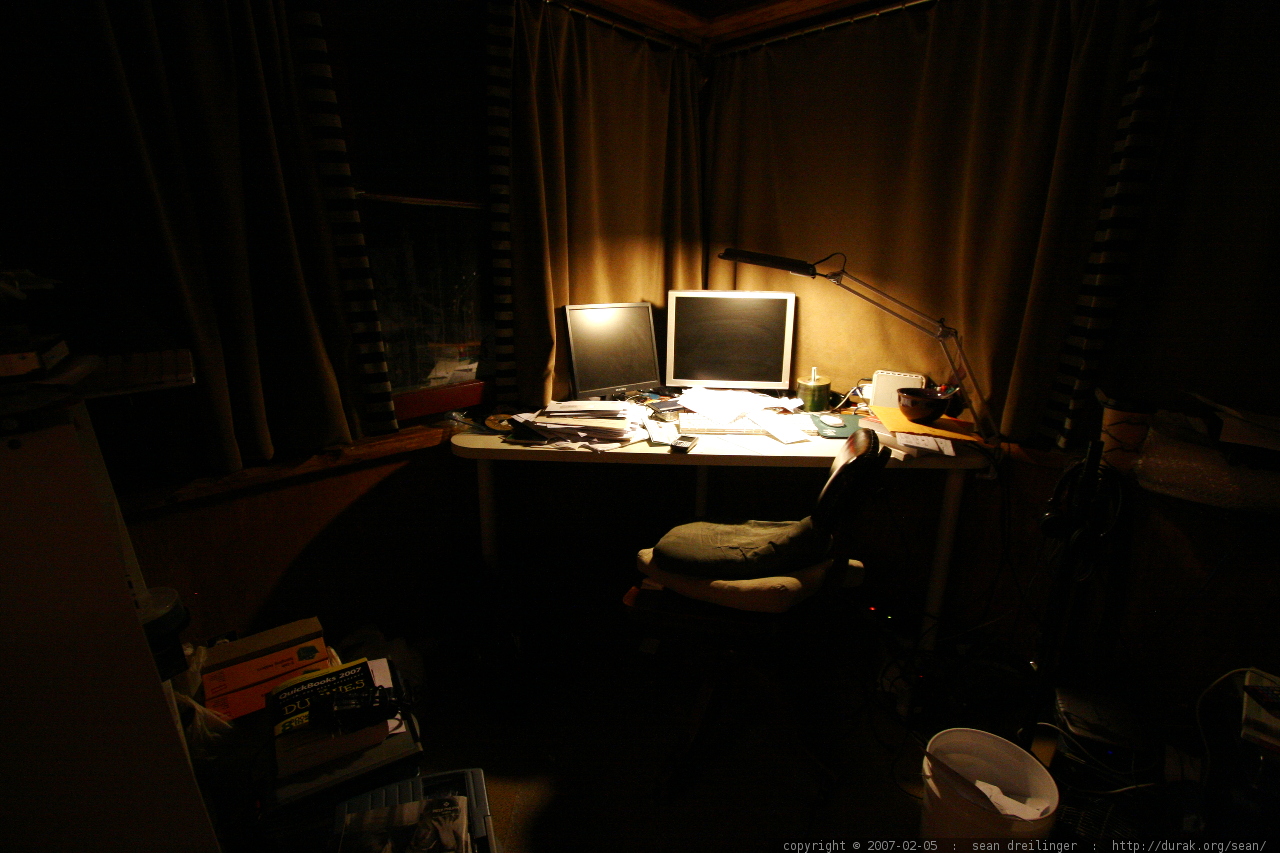

My dorm room was the size of a matchbox, and had an AC that went thunk-thunk-thunk when it kicked on and only emitted a tiny wisp of cold air that made the room muggy and your hands sticky like flypaper. I was 19. Not a kid anymore but far from being a man. Men knew who they were. Me, not so much. I was watching via a small phone screen in my small dorm room as an entire city was broken and beaten and burned—buildings turned to charred nubs and wooden rubble, all over the shooting of an unarmed Black man, Michael Brown. It was triggering. I was back under that carport all over again, imagining the muzzle flare that never happened and the closed casket that never was.

I had wanted to write about the Black experience in the South that night. Instead, the Word doc on my laptop remained blank and the crosshairs flickered off and on. I put my phone away so I could write, but my fingers just hovered above my keyboard.

Writing for me had always been a release, and though I’d lost my love for it for a time, I’d recently rekindled it. But every time I tried to write about my experiences as a Black man, the same thing happened: I doubted myself, and wondered if I was Black enough to write about the Black experience. It never took me long to come up with an answer to this question, and that night, I did what I always did: I clung to my feeling of insecurity like an old raggedy ass blanket I was scared to let go of, all ’cause it was familiar, ’cause it made me feel safe. I closed my laptop, scooted my chair back, exhaled, and went back to watching Ferguson burn.

*

Throughout my life it has not been uncommon for me to hear white peers say that certain Black people were “acting white.” It has typically been a critique of the way someone walked and talked, their interests, their personality, their upbringing. It commodifies “race” and turns it into something that depreciates or appreciates depending on what traits the accuser finds valuable or deplorable in you. It’s all rooted in racist ideologies painting Black people as hyper-violent, hyper-masculine, and athletic superhumans who are prone to living in poverty, ignorant, and expected to fail. These things are all lies. I’m reminded of how James Baldwin, who often spoke about the power of identity in conjunction with stories, begged Black folks to never believe the lies this nation told about us.

When I was growing up in New Orleans, a city that is majority Black, I hadn’t yet discovered that there were lies told about me. I had interests the racially ignorant would have considered “white” and I wore this “eccentricity” with a badge of honor, demonstrating an ignorant bliss only children unmarred by the world are able to have. I wasn’t interested in sports, but I loved comics, manga, and magic, and I wanted to be a writer when I grew up. At about the age of seven, I had a toy chest overflowing with stories and poems I’d written. I would sit on my carpet cross-legged while Invader Zim was on TV in the background, and would write about the adventures of “Apple Boy” and “Taffy Man.” But when I was eleven, Hurricane Katrina came. Our home was decimated, and that toy chest of stories turned to a saturated container filled with pieces of paper molded together, speckled with black fungi and brown water stains. It took a long time to get the house back to normal, and by that time my family and I had made a home in a small town 30 minutes across the spillway, right around what is known as Cancer Alley.

I lasted roughly three months in my new school before I started getting bullied and accused of acting white. A year later, I started at another new school, trying to reinvent myself but failing miserably. By age 13 I started to use basketball as a way to relate to peers. It helped for a time, but wasn’t a full solution—so by 14 I went into full basketball mode, discarding any part of myself that made people see me as anything other than what I wanted to be. In no time, the comics and manga and quirkiness stopped; I changed the way I talked, and the way I walked. But I’d resected so much of myself that I’d accidentally cut away the healthy parts that I loved—including the part of me that loved writing.

At that time, I had a shaky grasp on my identity, and to write your own story while being stuck in the margins is an act of rebellion, a breaking free of the stringent social structures that aim to keep you shackled and remove your humanity, all to make you a 2-D supporting character in someone else’s stories. I’d learn this later, but I was too young then, and far away from wanting to rebel against the social structures the naive have to navigate in order to fit in. So I hid my box full of new short stories behind my basketball duffle bag and Nike b-ball shoes. In time, I made more friends, and accusations of my perceived whiteness slowed.

*

When the school I went to my freshman year of high school closed down, half of my class moved to a school up the street in a tiny town not ashamed of its bigoted history. It’s what’s known as a “segregation school”—it was founded after the civil rights movement so white people wouldn’t have to go to school with Black people. This wasn’t, and isn’t, an oddity, nor was it a secret. There are schools in Louisiana that had segregated proms well into the 2000s.

At the tail end of Jim Crow, many white folks built their own schools and subdivisions in what’s now known as “The White Flight.” They hid behind white picket fences while funding was siphoned from Black schools, bleeding them dry until books fell apart and grades took a nosedive and paint on the walls in the hallways started to chip. The Southern states no longer wanted to shell out money for quality teachers who wanted to educate Black kids, and a lot of them had district funding tied to property taxes, so what worked as a rope to upward mobility for suburbia was a financial noose around the necks for Black folks. My new high school, though rural, was established in the same spirit: a brick and mortar reminder to Black people that we didn’t belong.

It took time to get used to the cultural differences after the transition, but over time it became easier. I became a part of my team’s varsity squad and became much more socially active. There was of course a good bit of micro-aggressive incidents, though, like the time a new white friend stepped across the threshold of my home and said, “It looks like white people live here.”

I stopped. “What you mean?”

Up until that point, most of the accusations of “whiteness” I’d received were levied against my traits. Now my home was getting this label. Confused, I let the topic go, and my friend and I went into my room and chilled as I wondered what else he’d find that he would deem “white.”

Experience had taught me that whenever I corrected a classmate or friend for their micro-aggression, I’d be treated as if I’d ruined some bit I never asked to be a part of; the aggressor would act like I’d taken offense to something that should’ve been a compliment. Living in a region of the United States that was created with your discomfort in mind is to be gaslighted constantly, made to think that your feelings are absurd and your intuition is delusion. You’re being raised in a place where the Civil War was actually fought against the dastardly North in order to preserve “states’ rights.” You’re constantly told to get over the racism of the past despite seeing Confederate flags wave from people’s homes. You’re made to feel that you should never be offended when a white friend calls someone a nigger, because there’s a difference between a “nigger” and a Black person, so why should you be mad?

When my friend said “It looks like white people live here,” I knew where the situation was heading. I was young and didn’t have the lexicon to state why what he’d said made me uncomfortable; to save time and energy and to avoid him telling me I didn’t hear what he said the way he meant it, I let it go.

The next few years passed by in a blur, things getting easier in some ways and harder in others. I quit the basketball team and instead started hoopin’ at the court right on the edges of my suburb; that same year, there was some bubbling up of racial tensions within my graduating class. Trayvon Martin was killed, and the Black and white students in my Home-ec class had vastly different opinions on the case. The court, in times like that, was my safe space. But sometimes, it was not. When I walked up one day and asked who had next, an older black man saw my school’s shirt and asked if I went to “———.” I said I did, and during the game felt elbows slipping into my ribs, my chest, the crook of my neck. Shit talking bounced around me. After the game, one of the men approached me. “You must think you fucking white or something.”

I went home, took my school shirt off, and decided to accept the fact that I was stuck between worlds, and trying to fit in the gap was only crushing me. I stuffed my basketball shoes in my closet, next to my box of stories, and closed the door.

*

The following summer, I went off to college. No basketball, no writing, still unsure who I was, not even sure yet what I really wanted to major in. My days were rote; my nights were spent frequenting mostly white college bars despite the fact some of these places used dog-whistle bigotry to let me know I wasn’t really welcomed. The signs outside no longer said “no negroes allowed,” but vague “dress codes” and ever-changing college ID requirements, along with declarations that “we reserve the right to withhold services” did.

Regardless, I went week after week, drinking until I blacked out, maybe hoping if I drank enough, the person I was would disappear, and the person I was meant to be would take the wheel. Or maybe I loved being in smoke-filled barrooms soaked in booze and longing and teen angst because it felt good to be around people just as confused as me. Or maybe I just wanted to drink enough shitty vodka until it hit that spot in the hippocampus that felt oh so sweet like marzipan, and I wouldn’t have to worry about who I was or how people viewed me because it was easier to pretend that I was something I wasn’t when I was absolutely fucking annihilated. For a night, I didn’t have to worry about feeling directionless and anxious, or think about my flimsy sense of self or my feelings of insecurity.

Hiding parts of myself became as natural as breathing at this point, and being an artist takes a level of honesty and vulnerability I didn’t have. I couldn’t and didn’t write.

But one of those nights out, I met a girl. This girl would later become my girlfriend, and then my fiancée. She accepted every part of me, and one night I drunkenly waxed poetic to her about how I used to love writing. I threw ideas at her and she nodded and the moonlight beamed down on us in the parking lot of a hotel complex not far from a tailgate we’d just left.

She must’ve heard the longing in my voice. Soon after, she brought me to Comic-Con, where I sat in on panels about the art of storytelling. I started frequenting the university’s library when we got home, scrounging for books that would teach me how to write. I scribbled shitty drafts in a bent and crinkled notebook while sitting on my dorm room’s linoleum floor. My anger and curiosity with this country carried me to nonfiction, where I found in the stacks the work of writers who looked and thought like me. I found myself in between the pages of the books by Black artists that came before me—the most influential being Baldwin. I heard his pleas to not believe the lies about me and felt emboldened by them.

*

When I think back on that moment in my family’s foyer when my friend said, “It looks like white people lived here,” I realize he believed the lies. His entire identity was hinged on believing the lies. He was also showing me the fluidity of race. How it can be morphed and bent and twisted in order to fit a narrative. My Blackness had to be erased ’cause Black folks didn’t live in the suburbs or have two-parent households; they didn’t excel at school or have hobbies outside of sports; they didn’t get gifted cars by their parents or have private dorms. And there’s abso-fuckin-lutely no way they get into Master’s programs without being Affirmative Action applicants. Anyone who has all of these qualities must in fact be white, because to be Black and successful is an aberration and to be anything other is the norm. Instead of revising their biases when confronted with contradiction, people move the goalpost to avoid the collapsing of their own identity. Their identities are built upon a lie, and when your identity is tied to lies, the truth is reprehensible, and to be critiqued is an attack.

I wish I could’ve known all of this years ago, but hindsight is twenty-twenty and to be young is to be willfully blind. Last year, I sat, yet again, watching another city burn, all due to a murder of another Black man. I watched via Twitter Live as the Minneapolis Police Department was torched, and its embers flickered to the night sky like fireflies. As I did years ago, when I was about 18 or 19, I went to my laptop, and started to write my story. This time, I got to the end. This time, I sent the story out, and it was published, by Buzzfeed News. I wrote more, and more, and more until I felt comfortable, and I no longer gave a shit about what my narrative was supposed to be. I focused on what it was: I am Black, a southerner, and a writer. I like to watch basketball, and I also like to watch anime and Marvel movies. My upbringing doesn’t shield me from the stressors of Black life, but it is a reminder of how far our people have progressed. Every time I write, like I am doing now, I do so with all of these things in mind.

This piece was originally published on September 28, 2021.