The Missing Wreath: On JFK’s Grave & Mrs. Mellon’s Maquette

“Let the word go forth from this time and place, to friend and foe alike, that the torch has been passed to a new generation …”

—Gravesite of President John F. Kennedy (1917–1963), Arlington National Cemetery (reinterment 1967), Quoting JFK’s Inaugural Address (1961)

“The wind bloweth where it listeth, and thou heareth the sound thereof, but canst not tell whence it cometh, and whither it goeth …”

—Headstone of Rachel Lambert “Bunny” Mellon (1910–2014), Trinity Episcopal Church Cemetery, Upperville, VA, Quoting John 3:8

I. Arlington

President John F. Kennedy Gravesite, Arlington National Cemetery, Arlington, VA. Photo by G. E. Henderson, November 2021.

Overlooking the Potomac River, Arlington National Cemetery doubles as an arboretum that has been called a “living memorial.” Manicured woods shade thousands of graves. Under branched canopies, headstones line grassy slopes like dominoes rolling down to parkways, neoclassical promenades, and roundabouts in and out of the nation’s capital. Under the rumbling flightpath of Reagan National Airport, with the occasional twenty-one-gun salute, the cemetery sits otherwise quietly surrounded by federal suburbs of northern Virginia. Those who live nearby commute by car or metro, bike or run past the forested landscape. Pastoral slopes border glinting high-rises of Rosslyn, historic red bricks of Fort Myer, the concrete Pentagon, and grand span of Memorial Bridge interconnecting Washington, DC, with thousands of graves.

To walk the cemetery’s seemingly peaceful grounds is to traverse centuries of conflict. Arlington shelters the remains of veterans and their spouses across American history and continues to inter those who die in the nation’s service. Exceptions commemorate other types of public servants, from Space Shuttle astronauts to Supreme Court justices including Thurgood Marshall. For those with buried loved ones, the cemetery acts as a portal to personal memory. As a “living memorial,” founded during the Civil War on requisitioned property of Confederate General Robert E. Lee, Arlington sits at a threshold of ongoing national reckoning.

Memorial Bridge aligns Arlington House with the Lincoln Memorial to symbolically realign the North and South with DC’s axial plan. The cemetery’s southern edge overlaps the historic site of Freedman’s Village, where formerly enslaved African Americans lived in freedom, and Sections 23 and 27 hold graves of those who served in segregated regiments during the Civil War. Before nationhood and colonial settlement, the riverine land was home to hundreds of Indigenous communities over centuries.

Beyond the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier (dedicated in 1921), the most visited grave is over a half-century old: the grave of President John Fitzgerald Kennedy. As one of only two presidents buried in Arlington (the other being William Howard Taft), JFK is interred amid a stone terrace overlooking Memorial Bridge and the National Mall. The plot spreads over three sloping acres, previously deemed unsuitable for burials, but acquired after JFK’s assassination on November 22, 1963. First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy wanted his gravesite to be accessible to the American public, and his Eternal Flame has since drawn millions of visitors from around the world. The president’s grave lies in a small sea of pink granite, edged by magnolias and evergreen hedges below slopes of trees, above an ellipse of his etched speeches. The contemplative site overlooks the nation’s capital.

On a crisp morning in late November 2021, I visited JFK’s gravesite (Lot 45, Section 30) amid the COVID-19 pandemic, too early in the holiday season for the annual laying of evergreen wreaths. Leaves of maples flared, oaks curled brown, and magnolias budded unseasonably, while other trees branched bare. An overnight dusting of snow had melted. The Eternal Flame whisked in the chilly wind, as occasional visitors—in couples and small groups, masked and unmasked—climbed the steps to stanchions around the grave.

I did not come alone but in the company of two who had previously visited the site: Lady (Elinor) Crane of the Oak Spring Garden Foundation and Nancy Collins, the foundation’s archivist. Oak Spring is the former Virginia estate of philanthropists Paul and Rachel Lambert “Bunny” Mellon; the latter was a close confidant of First Lady Jackie Kennedy and helped to design JFK’s gravesite. A few weeks before my visit, in October, Elinor had emailed me to say, “we got a great mystery to be solved. It involves a president, a first lady, a French sculptor, a French jeweler, two cemeteries, an ambassador, a four-star general, and Oak Spring. Hope that will keep you interested.” Now I stood with Elinor and Nancy beside JFK’s gravesite, looking at what was present and imagining what was absent: a lost artwork that they wanted to find.

II. Oak Spring

Shadow of Rachel Lambert “Bunny” Mellon overseeing stone-cutting for JFK gravesite at Oak Spring in Upperville, VA. Photograph by Bunny Mellon, December 1966. Courtesy of John F. Kennedy Presidential Library Archives.

When I first met Elinor in October 2020, she stood among graves in Oak Spring’s cemetery, weeding and cleaning headstones. Tucked away on a rural farm, the small graveyard is hemmed in by stacked stone walls and holly hedges, shaded by a deciduous canopy. The Oak Spring Garden Foundation (OSGF) lies in the shadow of the Blue Ridge Mountains in the Piedmont region of Virginia. I had come to the property for an ecology seminar, and when our group approached the cemetery, Elinor stood up from the stones and introduced herself by her first name, as “Head Volunteer of no other volunteers,” in a department where “all of my staff lie underground.”

Originally from Chicago, with a roll-up-your-sleeves wit and penchant for history, Elinor seems at home at Oak Spring. She regularly rummages through attics and basements, weeds gravestones, and walks the grounds with the Cranes’ aged beagle, Darwin. On the footer of her email address, she drops her title of “Lady” in favor of her self-appointed title as “Head Volunteer.” She moved to Oak Spring when her husband, Sir Peter Crane, became OSGF’s founding president in 2016 after the death of Rachel Lambert “Bunny” Mellon (b. 1910–d. 2014). A renowned paleobotanist, Peter Crane formerly directed Chicago’s Field Museum and the UK’s Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, also serving as dean of Yale’s School of Forestry & Environmental Studies (now Yale School of the Environment). Peter and Elinor live in a house by the stables, now renovated as live-work suites for researchers. While he focuses on environmental and administrative initiatives, she serves as an ambassador to visitors and excavates the Mellons’ history on site.

What was once the epicenter of the Mellon’s global activities, Oak Spring (with adjoining Rokeby Farm) lies about an hour from the nation’s capital near the picturesque village of Upperville, Virginia. Between the Blue Ridge and Bull Run Mountains, the Mellon estate once stretched over four thousand acres, across forested slopes and equestrian farms, carved by streams and stone walls, and studded with art-filled homes, greenhouses, ponds, and barns. When Bunny Mellon died in 2014 (fifteen years after her husband, Paul), most of the Mellon’s remaining art, furnishings, and land were bequeathed, sold off, or auctioned at Sotheby’s to ultimately raise money for her foundations, including the Gerard B. Lambert Foundation (which she founded in 1976 and named after her father) and the Oak Spring Garden Foundation (founded in 1993). After her death, her estate distilled a few hundred acres to focus on her special collections library, main house garden, and adjoining acreage that grew into a biocultural conservation farm. At heart, Bunny was a gardener, with a private practice that shaped the White House Rose Garden, the John F. Kennedy Gravesite, the JFK Presidential Library and Museum, Potager du Roi at Versailles (Louis XIV’s kitchen garden), and many elite private gardens and grounds for her personal friends.

The Oak Spring Garden Foundation emerged as Bunny’s legacy to steward a changing landscape. OSGF now manages around seven hundred acres, evolving to support residencies for scholars and artists, short courses for environmental practitioners, initiatives in community-supported agriculture, educational outreach, and related programs to cross-pollinate all things botanical.

As Elinor recoups Oak Spring’s relics in and beyond the property, she works with legacy staff from the Mellon era, including archivist Nancy Collins, who accompanied us to Arlington National Cemetery. Nancy started working for the Mellons part-time in the 1980s as Paul’s private nurse and moved full-time to Oak Spring in a nursing capacity from 1994 until Bunny’s death in 2014. Nancy is a motherly soul from West Virginia whose caretaking has transitioned to Oak Spring’s library. Among other staff, Elinor also works closely with Bunny’s former driver, Jay Keys, a native of Virginia (who drove us to Arlington) who started working for the Mellons in 1982 and now chauffeurs guests. Jay also accompanies Elinor to estate sales, flea markets, and Goodwills to help refurbish buildings across the estate emptied from the Sotheby’s auction so that OSGF can host more visiting scholars and artists. Both Nancy and Jay say that “Mrs.” (Mellon) treated them like family, and they have since grown close with Elinor while reviving Oak Spring’s history on site.

As Elinor and her aides-de-camp have poked through crates in attics of barns and boxes in basements, they have found material witnesses that auction appraisers overlooked: a bronze sculpture of a medieval-style The Maiden and The Unicorn (one of three commissioned sculptures by Heinz Warneke, now installed in the garden); linens embroidered with Oak Spring’s insignia and floral fabrics (including bolts of bright blooms that have since revitalized the Poppy Room, where Jackie Kennedy and her children stayed during visits); and a small frame of pressed dried flowers (once hung in the Mellon residence), with handwriting that reads: These flowers collected by Perry Wheeler from flowers RLM [Rachel Lambert Mellon] picked in Rose Garden to make basket of flowers for Pres. Kennedy’s grave on the day of his funeral at the request of Mrs. Kennedy. November.

Since Elinor moved to Oak Spring, her favorite revitalization project has been its cemetery, where her “mystery” emerged.

III. Stone Maquette

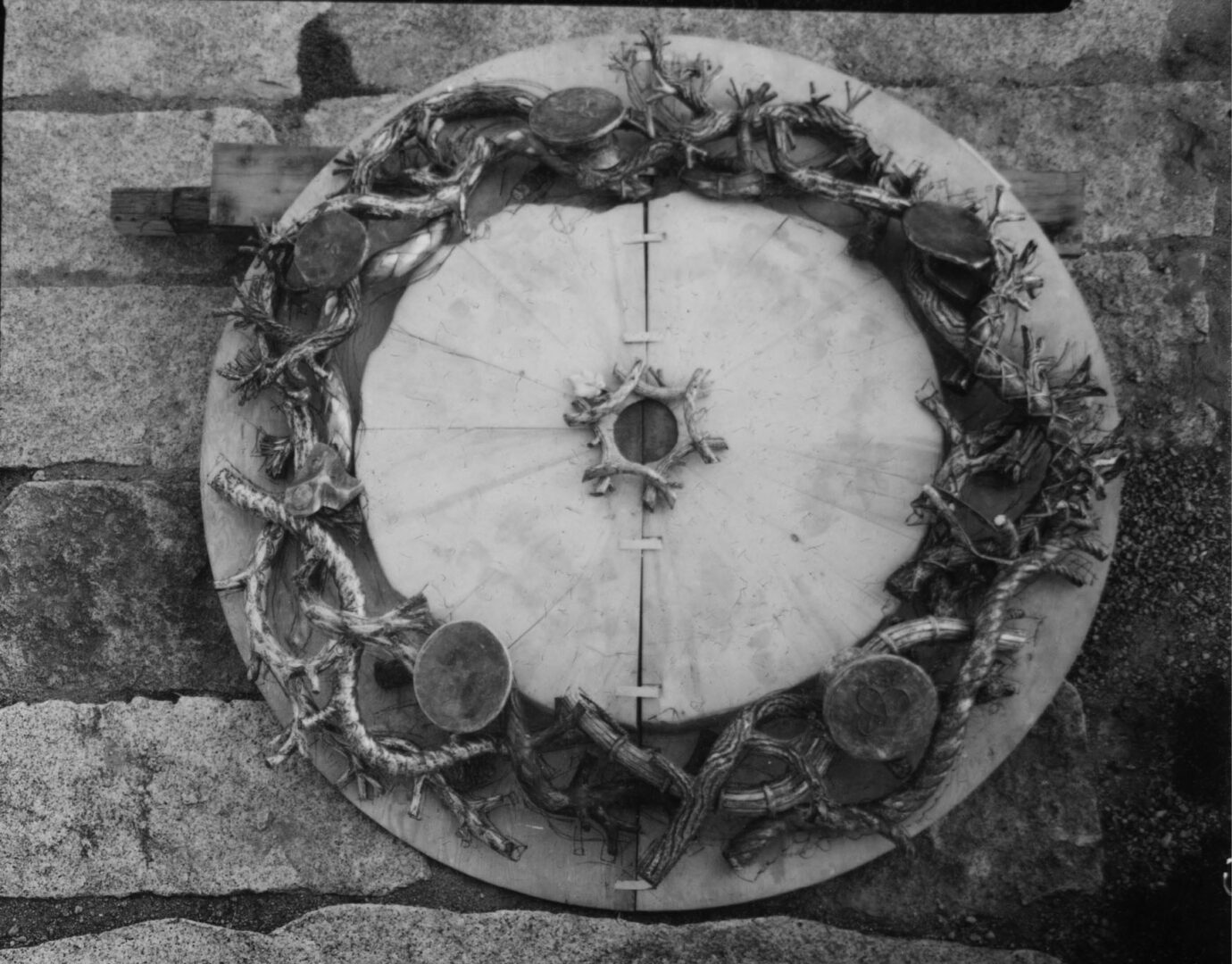

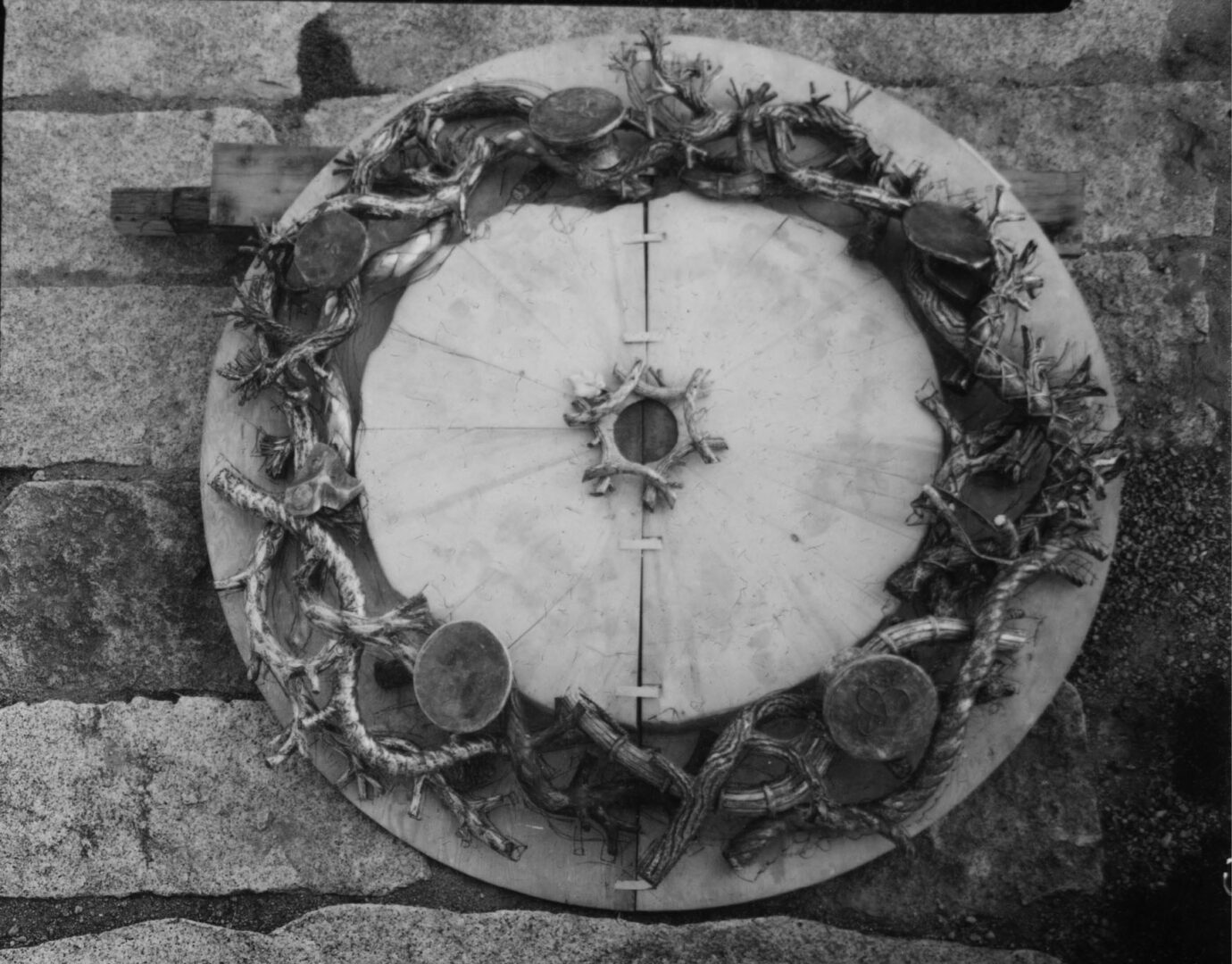

Stone maquette related to JFK gravesite in Fletcher Cemetery at Oak Spring Garden Foundation, Upperville, VA. Photo by G. E. Henderson, November 2021.

The Oak Spring cemetery, also called the Fletcher Cemetery (after a nineteenth-century colonial settler of the property), sits within a stacked-stone fence. On a knoll shrouded by leafy trees, the graves lay away from the Mellon’s home: an aged white brick residence with interlinked guest houses, walled around Bunny’s famed garden. The assemblage resembles a French hamlet, not regal but rather elegantly quaint. With the garden as destination, visitors tend to miss the cemetery—unless you stroll beyond the residence, downhill past the namesake spring house, around the pond, uphill through mown grasses around pruned apple trees, to the walled enclosure. Within, the cemetery resembles a woodland park. The Mellons relocated their family graves to Trinity Episcopal Church Cemetery in Upperville in 1996, leaving behind weathered gravestones of inhabitants from as early as the 1840s (and who, according to the property deed, require “perpetual maintenance and care”). In recent years, the aged graves in Fletcher Cemetery have been visited mainly by deer, squirrels, birds, and Elinor.

In fall 2020, as Elinor cleaned and weeded the historic headstones (around the time I met her), she stumbled upon an enigma: a circle in a square of oyster shell stone (a porous sedimentary rock from ancient seas). These disintegrating cracked slabs lay in a separate quadrant of the cemetery than the limestone and granite headstones. Weeds grew through the cracks. She initially mistook the stone assemblage for an abandoned picnic patio. A former employee had said it was a maquette (a preliminary model) for JFK’s grave in Arlington, and a biographer of Bunny Mellon had used that source, understanding it to be created in preparation for JFK’s reinterment in March 1967. The stone maquette remained as a quiet, disintegrating reminder of the president’s presence.

As Elinor cleaned and documented graves in Fletcher Cemetery, more details grew around the stones. Oak Spring’s long-time stonemason, Tommy Reed—who started working for the Mellons in 1972 as a high school student and who still works on the property (almost a half-century later!)—brought some washing water for the graves and shared his memories of making the oyster stone maquette in his early years, alongside a senior stonemason named Harold Lovett. After the maquette was made, a sculpture of some sort was left on it, Tommy recalled, something gnarled with hats. He was told to let the metal stay on the stone to weather and age. The mysterious object left quickly and quietly as it came, in the middle of the night. (“The Mellon way,” Elinor tells me later. Staff didn’t ask questions. “If you weren’t told, you didn’t ask.”) The oyster stone maquette in Fletcher Cemetery remained beside the older gravestones, eroding along with fading memories.

There was a discrepancy in origin stories about the stone maquette that snagged Elinor’s attention. The maquette’s design of chiseled blocks around a circular stone resembled JFK’s gravesite, but the dates were off, and she hadn’t heard of a sculpture associated with the grave. She started researching the president’s gravesite and enlisted Nancy to cull through the archives of the Oak Spring Garden Library to learn more about Bunny’s involvement.

In simplified form:

After JFK’s assassination in Dallas on November 22, 1963, First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy asked her close confidant Bunny Mellon (who had designed JFK’s White House Rose Garden) to arrange the funerary flowers for the White House, Capitol, and gravesite. Three days later, JFK was buried at Arlington National Cemetery in a State Funeral where Jackie lit the Eternal Flame.

Weeks earlier, at services for Veteran’s Day, JFK had laid a wreath at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier and earlier that year had visited the overlook and was overheard saying, “I could stay here forever.” Although the hillside in Arlington had previously been deemed unsuitable for burials, JFK’s brother, Attorney General Robert (Bobby) Kennedy, and Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara helped to secure over three acres for the Kennedy plot. The commission to design the formal gravesite went to the architectural firm owned by John (Jack) Warneke, who had worked with the Kennedys to preserve historic Lafayette Square near the White House and who had become part of their circle. A multi-year undertaking ensued, involving detailed, confidential research reports (with historical context to distinguish whether the burial site should be a memorial, monument, or grave); consultations and critiques by prominent family, scholars, architects, and art critics; a public exhibit of design plans at the National Gallery of Art in November 1964; and coverage in major news outlets.

Jackie Kennedy wanted the gravesite to be publicly accessible yet personal as a family grave and worried that any monumental grandeur would counter the spirit of her late husband. As plans proceeded in 1964, she designated Bunny to represent her wishes in the grave design. (Then first lady, Lady Bird Johnson, also enlisted Bunny to finish the White House East Garden that was renamed in 1965 as the Jacqueline Kennedy Garden.) Bunny assembled stonemasons, gardeners, and arborists who worked with her around Oak Spring and in Washington, including Warrenton-based contractor W. J. Hanback, DC-based landscape architect Perry Wheeler, and other counterparts.

As debates circulated within the family and beyond (regarding the grave’s monumental versus personal attributes and styled font for the flame), Bunny softened the site design. She selected pink granite from New England, rough cut to resemble the waving sea of Cape Cod that JFK loved. Granite blocks were spaced for fescue and clover to grow between cracks. Instead of a grand marble backdrop of a wall with the presidential seal, she eliminated the wall and naturalized the border with evergreen boxwood, signature magnolias, and other specimen trees, flowering plants, and shrubs that would evoke the Rose Garden. Instead of a religiously symbolic torch or abstract art to hold the Eternal Flame, she found weathered granite, large and round and aged as a New England millstone. A marble stairway (newly built into the cemetery’s hillside to connect JFK’s gravesite with the historic Arlington House) was removed and recovered with lawn. Bunny’s design was meant to be timeless and elemental: stone and fire, light and shadow, greening and branching and blooming through seasonal cycles.

On March 14, 1967, the president was reinterred in his final gravesite. Even as Bunny worked behind the scenes and attributed landscape design ideas to Jackie Kennedy, her involvement was publicly credited at the time. As art and architecture critic Wolf Von Eckardt wrote in the Washington Post (March 26, 1967): “What is much for the better is that Mrs. Paul Mellon’s superb landscaping has beautifully and gracefully blended Warnecke’s cold granite and marble into that beautiful, natural hillside rolling down from the Custis-Lee Mansion [now Arlington House].”

The design of JFK’s gravesite was formally completed July 20, 1967 (as stated on the current websites for both Arlington National Cemetery and the JFK Presidential Library and Museum), for posterity to witness quiet changes over seasons and subsequent years. Magnolias bloomed each spring, and oaks dropped their leaves in fall, with year-round evergreen hedges. The Eternal Flame occasionally blew out and was engineered to better withstand rain, wind, and snow. Millions of visitors have come to pay their respects, year by year. Over decades, more Kennedys were interred near JFK: wife Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy Onassis (who died in 1994) in the immediate family plot (alongside two offspring who had died in infancy and were interred originally with JFK); in proximity to a memorial marker for brother Joseph Kennedy, Jr. (who died in 1944), Robert (Bobby) Kennedy (1968), and Edward (Ted) Kennedy (2009). In 2011, Hurricane Irene felled the majestic Arlington Oak (that had stood in JFK’s viewshed when he last visited Arlington in 1963), estimated to be over two centuries old and replaced by a sapling grown from the seedling of the great oak tree.

The gravesite remained relatively unchanged over decades. Meanwhile, the world transformed.

As 2020 moved toward 2021 amid a global pandemic and national and international discord, Elinor Crane could not understand why the stone maquette in Oak Spring’s Fletcher Cemetery was created a half decade after the completion of the JFK gravesite. The deceased president was reinterred in his final grave in Arlington in 1967, but the Oak Spring stonemason who made the stone maquette didn’t start working for the Mellons until 1972. The timeline seemed backward. Something was missing from the story.

IV. The Hats

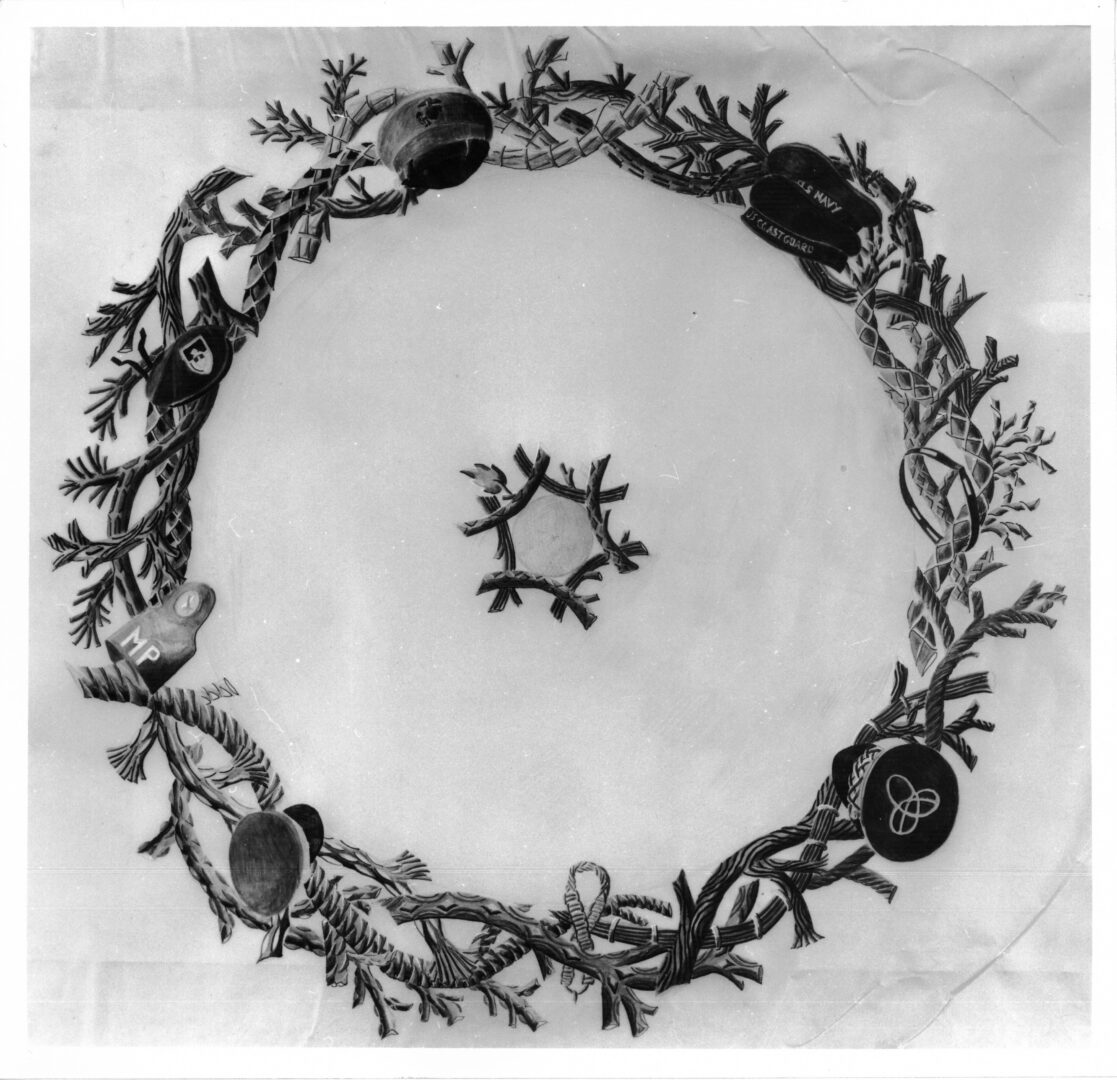

Military hats from JFK’s funeral entourage laid as impromptu wreath on his temporary grave. Image provided courtesy of US Army Corps of Engineers and John F. Kennedy Presidential Library Archives.

Rewind to November 1963: to JFK’s epic funeral. The world stops to watch the televised black-and-white broadcast in collective mourning. Moments unfold in Washington, DC: with the American-flag-draped casket, the mass without eulogy, the somber procession through the nation’s capital. Jackie’s elegant, stoic grief; young John-John’s salute to his father’s coffin. When the procession finishes in Arlington National Cemetery, representatives of the armed forces’ pall bearers pay their respect to the slain president and, in a spontaneous gesture, lay their uniformed hats around his burial mound. When Bobby Kennedy sees the impromptu memorial wreath, he is moved to say that the hats should remain around the grave until they “crumble to dust.”

Between JFK’s temporary and permanent interments (1963 and 1967), the hats marked his grave so prominently that an early proposed design for the gravesite included a plaque to commemorate them. Through snow and sun, season after season on the temporary grave, the hats remained, at times replaced due to weathering, and they reappeared in photographs, articles, and other accounts. (Elinor keeps a photograph from her family’s visit to the gravesite in 1965, when she was aged four, showing the grassy mound and Eternal Flame encircled by hats inside a white picket fence.) In evolving designs for the gravesite, a bench for Jackie Kennedy was proposed near a plaque commemorating the hats. The spontaneous wreath encircled not only a president’s grave but also a nation’s grief. The wreath of hats represented a communal homage to a fallen national leader who had been the youngest American president-elect to date and who, to so many, had represented a hopeful future.

As the 1960s progressed, the meaning of the hats weighed more heavily. Against a backdrop of tumultuous civic and global events, including the escalating war in Vietnam, Bobby Kennedy questioned whether a military display should remain associated with his brother’s gravesite. Public criticism of the hats grew with the antiwar movement, peaceful protests, and violent backlash around Civil Rights. Shortly after the reinterment, Wolf Von Eckardt wrote “A Critical Look at the Kennedy Grave” for the Washington Post (March 26, 1967), calling the hats “absolutely silly,” adding, “It was a touching gesture when, at the president’s funeral, the soldier, sailor, marine, and airman spontaneously removed their hats and left them with their Commander in Chief,” but now “should be removed altogether.” He added, “We’ll have the photographs of the funeral to remind us of that spontaneous gesture. Less is more. And nothing should be allowed to mar the dignity of this monument which Warnecke has designed with such admirable restraint and which is sure to grow in the Nation’s affection as Mrs. Mellon’s trees flower and mature.”

On April 18, 1967, the Washington Post reported “Military Hats Banished at JFK Grave” after the hats were “quietly removed” by “unanimous” decision. Deemed an “inappropriate adornment” for the new design, the hats were noted as “distracting from the beauty and simplicity of the grave.” After their removal, the landscape received final treatments until the gravesite was deemed complete later that year.

Yet, behind the scenes, the hats had an afterlife—as Elinor and Nancy started tracing in 2020—backward from Oak Spring’s crumbling maquette and forward to when a memorial artwork went missing in the early 1970s.

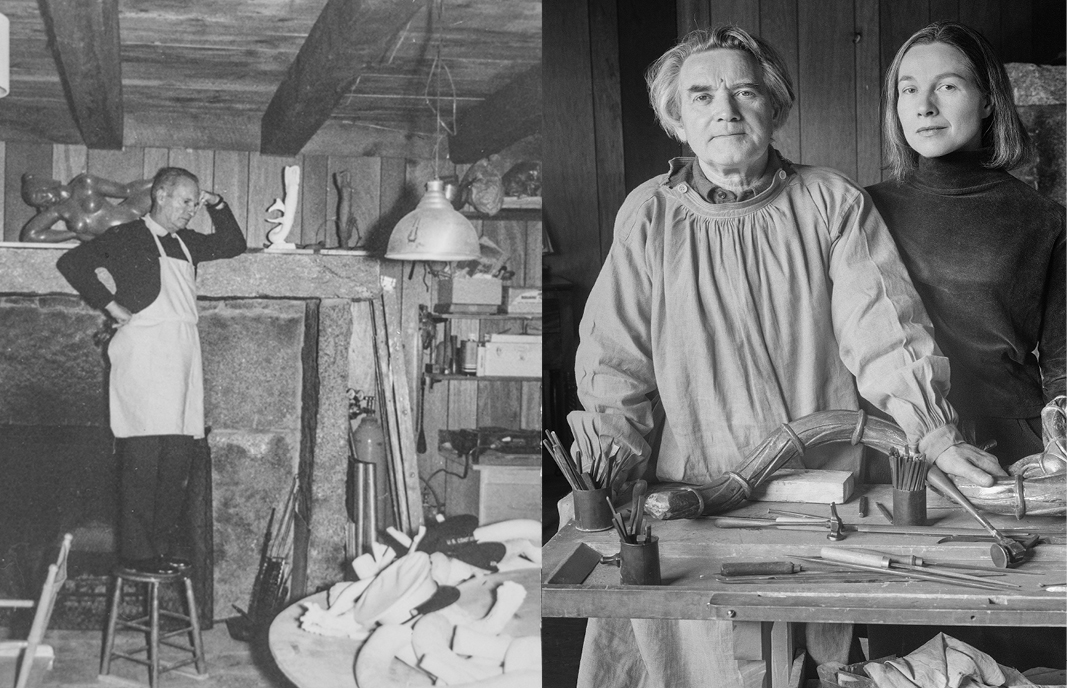

After Elinor talked with the Oak Spring stonemason Tommy Reed and learned of the discrepancy around the maquette’s origins, Nancy recalled a photograph from 1969 in Oak Spring’s archives showing assorted hats coated in plaster on the floor of an artist’s studio. Looking on in the photo is Jean Schlumberger, a renowned French-born Tiffany jewelry designer and Bunny’s confidant and collaborator over many years. As Nancy dug into Schlumberger’s archived correspondences, some of his letters alluded to a sculpture-in-progress as a “memorial wreath” for JFK’s grave. Designed by Schlumberger, the memorial was to be made by a French sculptor who also lived and worked in the United States, Louis Féron.

With this knowledge in January 2021, Nancy reached out to JFK’s daughter, Caroline Kennedy (then serving as US Ambassador to Japan before her current ambassadorship in Australia), to inquire if she knew of a sculpture by Schlumberger planned for her father’s grave. Caroline remembered the sculpture and vaguely recalled being told that the wreath was too large and heavy for display, that it may have been returned to the Mellons or gone to a museum in Richmond. Many Virginia museums with associations with the Mellons were contacted without success. Caroline also connected Nancy with the JFK Presidential Library and Museum in Boston. The JFK Library shared digitized documents, including sketches and photographs of a “memorial wreath” of hats in a file on Schlumberger (donated posthumously by his life partner, Lucien Bouchage). The file had photographs in common with Oak Spring’s collection, including the image of Schlumberger in Féron’s studio overseeing the plaster model of the wreath with actual military hats, likely a set from Arlington National Cemetery. Additional documents slowly grew the ghost of a missing sculpture, but the memorial wreath itself was nowhere to be found.

All who had been close to the artwork’s creation had died: Bunny Mellon (1910–2014), Jackie Kennedy (1929–1994), designer Jean Schlumberger (1907–1987), sculptor Louis Féron (1901–1998), architect John Carl Warnecke (1919–2010), landscape architect Perry Wheeler (1913–1989), Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara (1916–2009), General Counsel of the Army Alfred Fitt (1923–1992), and spouses, including Bunny’s husband Paul Mellon (1907–1999), as well as her two children. Most staff members at Oak Spring and Arlington National Cemetery from that era also had died.

As 2021 progressed, Elinor and Nancy—who started referring to each other as “Sherlock”—contacted dozens of archives and related organizations asking if anyone knew about the missing artwork. In March, Elinor learned of an autobiography by Louis Féron (posthumously published by his widow, Leslie Snow, in 2014 under the title A Voyage Remembered) that included some photographs of the sculptor holding cast pieces of an unidentified sculpture and of the couple proudly holding what appeared to be the missing wreath, disassembled. Notably in the photographs, the sculptor wore the same smock and appeared the same age, yet the photos were captioned over a decade apart (1966 and 1978). Through an eBay search, Nancy found archival photographs of a cast wreath by Féron—mislabeled as “War Art”—from the dispersed estate sale of Snow (who had died in 2017, almost 20 years after her husband). The archival photos echoed materials archived at the JFK Library. Identifying the photographer as Evelyn Hofer, Nancy contacted the executor of her estate and later learned that the photographer’s personal calendar of May 16, 1969 had noted a commitment in “Snowville,” New Hampshire, with “Louis and Leslie Féron.”

More pieces of the puzzle emerged and led Elinor into a self-described “vortex.” In October, she invited a retired four-star general previously associated with Arlington Cemetery to visit Oak Spring to learn about the National Cemetery’s involvement in the memorial wreath; he tried to help in the search, but his inquiries at Arlington and various associated military museums and storerooms met dead ends. In November 2021, guessing that the sculpture would have been cast at a regional foundry near Féron’s home (in New Hampshire), Nancy located the Modern Art Foundry in New York that had receipts confirming that a “memorial wreath” had been cast for Féron in 1969. Around this time, Nancy also visited the Smithsonian Archives of American Gardens to research Perry Wheeler, who was Bunny’s collaborator on landscape architecture projects, including the White House Rose Garden and JFK’s gravesite. Related records emerged, but nothing led to the missing sculpture.

From Elinor’s original inquiry, a shadow story arose around the memorial wreath for JFK’s gravesite. The artwork was variedly described across documents with words like “memorial wreath,” “president’s tomb,” “president’s grave,” “memorial,” “monument,” “adornment,” and more. Envisioned around 1966 by Bunny Mellon with designer Jean Schlumberger, and involving Féron by 1967, the artwork was formally commissioned by Jackie Kennedy in 1968, with a plaster model of the sculpture executed by Féron in the following months, cast and finished by the Modern Art Foundry and professionally photographed by Evelyn Hofer in 1969. The memorial wreath would have encircled the large, round stone at JFK’s gravesite—approximately five feet in diameter—on which the Eternal Flame burns. In the early-to-mid 1970s (sometime after Tommy Reed started working at Oak Spring in 1972), the cast sculpture presumably came to Oak Spring to temporarily adorn the newly made stone maquette, “to weather and age” in the Fletcher Cemetery for the purpose of deciding if the sculpted wreath should ornament JFK’s gravesite at Arlington.

The rest falls into conjecture. The artwork disappeared without a trace. JFK’s memorial wreath wasn’t considered stolen, just not discussed or questioned, not even missed—essentially lost to time.

This lost artwork is what Elinor and Nancy hope to find.

V. The Library

Oak Spring Garden Library, Oak Spring Garden Foundation,

Upperville, VA. Photo by G. E. Henderson, April 2021.

After Elinor and Nancy bring me to Arlington National Cemetery (driven by Jay “like old times with Mrs.”), we spend a few days in the Oak Spring Garden Library. In the shadow of the Blue Ridge Mountains, a larger story emerges.

The Oak Spring Garden Library is arguably Bunny Mellon’s masterpiece: a collection of rare books and manuscripts related to horticulture, botany, gardening, and natural history. Amassed over her lifetime, the collection became her self-taught education, shaping her gardening aesthetic and landscape design.

The library was designed by modernist architect Edward Larrabee Barnes and completed in 1981, with a new wing designed by Thomas Beach completed in 1997. The building’s heart is a veritable reading room of blooms, with high windows and pickled oak bookcases, frequently shuttered to protect the rare books from sunlight. In the modern sanctuary, antique furnishings mix with botanically patterned sofas and chairs; among historical artworks hangs a massive sunburst canvas by Mark Rothko (a reproduction, since the original was sold upon her death to a private buyer). Walls host abstract paintings by Bunny’s predeceased daughter Eliza. The library also includes two blue-and-white French country kitchens, with a similarly tiled bathroom and tub. The upper-level drawing room formerly contained a French steel-framed bed where Bunny would occasionally nap among her books and art.

Within this distinct collection, the creator’s archives live in its vault. Bunny’s personal archives are mediated by archivists who protect the privacy that she curated in life (also following protocols of the Gerard B. Lambert Foundation that she set to oversee the library, including after her death). As an heiress to the Listerine fortune, Bunny had ample resources to grow a venerable collection even before she met Paul Mellon (and her first husband, Stacy Barcroft Lloyd, Jr.). Since her father felt that further education was not necessary for either of his daughters, she did not attend college after boarding school at nearby Foxcroft, and her evolving library became the crucible of her education. The librarians—including Tony Willis, who bench-trained under Bunny beginning in 1980, when he was in high school, and whose parents and brother worked for the Mellons—are invested in keeping the library alive as Bunny’s legacy, welcoming scholars and artists and ecologists as if to a friend’s home.

At one of the research tables, Nancy settles me with boxes of archival and reproduced materials related to the JFK gravesite. Over six feet tall with dark brown hair, Nancy is an independent spirit, down-to-earth and welcoming. She leaves me to sort through the mix.

There are sketches and photographs of the missing sculpture. Architectural renderings of the gravesite. Memoranda and memorabilia around JFK’s funeral, burial, and reinterment. Related photographs sit in plastic sleeves and boxes of slides. Reports and articles outline the evolving design plans and steps for implementation. Records show contractual logistics of contracting, landscaping, engineering, and stonemasonry. Professional and personal commendations appear after the gravesite’s completion.

Different collections carry different materials. Unwittingly, I read pieces out of order. As I cull through materials, time travels back to 1963, 1964, 1965, and subsequent years.

In November 1966, a “Memorandum to Honorable Robert S. McNamara Secretary of Defense” summarizes a meeting between Bunny, Michael Painter (one of Warnecke’s associates), and members of the US Army Corps of Engineers. It stipulates that “the grave plot will be duplicated at Upperville,” referring to materials prepared at Oak Spring for the Arlington gravesite. In other archival files, photographs illustrate that the stones were irregularly cut, fitted, and numbered at Oak Spring to be repuzzled together at Arlington. The job involved staff who worked with Bunny around Oak Spring, including contractor W. J. Hanback, who had helped Bunny rebuild Trinity Episcopal Church in Upperville in the years before JFK’s gravesite. The pages of the memorandum essentially finalize the plan with two details “to be worked out some time in the future,” namely “a bench for Mrs. Kennedy’s use at the grave terrace” and “the creation and installation of a plaque memorializing the military caps left at the president’s grave the day of his burial.”

As I cull through photographs and printed reproductions, a skirted figure overshadows a field of interconnected stones. Nancy identifies the figure as Bunny in silhouette, overseeing her work. Staff identify the location as Oak Spring’s long-gone Stone Shed, where the stones were cut and fitted in preparation for Arlington. The photograph is dated December 1966. Another photo in the same set shows a large round stone, resembling an aged millstone, that was selected to hold the Eternal Flame; it sits amid granite blocks being pieced together like a puzzle.

Elinor joins me at a neighboring table to look through unsorted slides. She places them in a lightbox and magnifier to identify them. Researching in the library seems to be part of her routine at Oak Spring, where she chats with library staff between her commitments beyond the cemetery. She regularly gives private tours of the property for visiting scholars and other guests, cultivates relationships across Upperville and surrounding communities, and co-curates exhibits in the Oak Spring Gallery (the penultimate building constructed during Bunny’s lifetime as a “Memory House”). Elinor and the library staff are friends more than colleagues, and each morning, the Cranes’ beagle, Darwin, comes by the library for dog treats. Elinor’s co-curated exhibits include an upcoming display on Bunny’s linens (which she wanted to title “The Mellons: Between the Sheets” but settled on “The Fabrics of Life”). In 2020, she co-curated an exhibit with Nancy on jewelry designer Jean Schlumberger, centered around his sculpted floral finial that once graced the roof of Bunny’s greenhouse. (The recently conserved original was installed around the time of JFK’s presidency; a replica now stands in its stead.) The sculpted lead finial—a grand bouquet in an urn—is the largest-known sculpture by Schlumberger. Only JFK’s memorial wreath, if found, would eclipse it.

In photographs, people come and go: stonemasons, military personnel, gardeners—even a rare sighting of Bunny herself, facing the camera (she did not like to be photographed, I am told). People also come and go amid correspondences: of handwritten pages, curling cursive, light pencil or dark pen or typed on paper, edged with age. International air mail feels delicate to touch. Among repeat correspondents are scripts and signatures, insignias and letterheads, including the sky-blue stationary of Oak Spring. Reproductions show Jackie Kennedy’s handwriting in graceful loops, while Bunny’s script rounds smaller, neater, tighter, almost cautious. Probing dashes extend penned thoughts—

Although Bunny Mellon and Jackie Kennedy circulate publicly as mythic types (a billionaire’s wife and president’s widow, the consummate gardener and America’s queen), the two “best friends” grow more dimensionally human in the private sphere. Even as it feels impossible to fathom their dynastic histories and lifestyles, a visit to the Oak Spring Garden Library somewhat humanizes their public specters. To humanize isn’t to neglect their exorbitant privilege, but what strikes me in handling archival materials like these is the common, devastating weight of grief. Regardless of privilege, no one can buy themselves out of death.

A grave may seem inert as a stone, yet it marks human life, vulnerable and fragile. A mere page of a handwritten letter carries something residual, fleeting as emotional time-travel. Such elements invite a raw, tender touch of lives once present, thrown into relief by retrospect.

Among archival materials is a typed document by Jackie Kennedy in response to Warnecke’s design, with an attached note dated September 14, 1966, relaying that she sent copies to Bobby Kennedy, Warnecke, and Bunny—noting that Bunny already knows her sentiments about the grave and will act as her representative. To offset the monumental aspects of the design of the larger gravesite, Jackie describes how the graves within should feel intimate for a family, a place where beloveds might go to lay flowers and weep, and also a place of peace for the deceased, surrounded by growing plantings or as if overlooking the sea.

After JFK’s reinterment in March 1967, Jackie wrote to Warnecke that her husband’s grave turned out exactly as she wished, as she asked Bunny to make it: as if JFK were buried in his beloved Rose Garden and washed over by the sea of his beloved Cape Cod.

Many letters are restricted so Nancy will not share them. She previews them for content related to the gravesite and reads aloud excerpts to me. At times her eyes get teary, reading details in silence. Jay occasionally drove Jackie and later tells me with simple admiration, “She was a very nice lady.” Caroline and John Kennedy, Jr. were in the wedding party for Bunny’s daughter, Eliza. The library holds a small, framed photograph that includes John, Jr., who Tony remembers kindly, saying that Bunny considered him a grandson. The inner sanctum feels small.

Given the Mellons’ closed circle, I am aware of being an outsider. Although I was invited by the Oak Spring Garden Foundation to write this story, I came only indirectly after learning of Bunny in tandem with my introduction to her legacy through her library and an ecology seminar at OSGF in 2020. Biographers have written books on Bunny’s elite life and complicated character, but my writing interests lie where ecology and culture meet, as libraries grow from landscapes—which drew me to her plant-rooted library, emerging biocultural conservation farm, and the myriad ways that future generations may learn from interrelated environmental-cultural histories.

As Oak Spring evolves, the memorial wreath—or more aptly, its loss—grows beyond the thing itself. Historical artifacts never exist in a vacuum, and inanimate objects have lives and even afterlives. Public and private events color retellings; an artwork can be curated dozens of ways, even to the point of disappearing behind variations of accounts. The aura around the memorial wreath’s absence makes it almost more powerful than if it were present. When public celebrity is involved, when privacy is fiercely guarded, when privilege can determine what is noticed or neglected or even erased, stories can constellate between private records and the public imagination. In the gray space where fact meets myth, truth tempts speculation. Histories can get lost between lines and behind headlines—just as a crumbling stone maquette in a rural cemetery can lie for decades without notice.

Nancy tells me that Bunny never talked about the stone maquette in Fletcher Cemetery. As Bunny’s nurse and companion, Nancy visited the cemetery with her regularly after one of Bunny’s close companions, Robert Isabell (1952–2009), died and was buried near the stone maquette. It lay right in their viewshed when visiting, but Bunny never said a word about it to Nancy. Tony and others who had long worked for the Mellons hadn’t ever heard of the memorial wreath before Elinor started inquiring. And no one seems to know the sculpture’s whereabouts.

But there are theories.

Newer staff joke that the artwork may be hiding in plain sight: in an unmarked crate in the attic of a barn (like the sculpture of The Maiden and The Unicorn was discovered in the so-called “Party Barn” by gardeners in 2021), in the back of a garage, or even sunk to the bottom of Oak Spring’s namesake spring. Much of the estate was sold off, including The Brick House (where Paul Mellon had lived with his first wife, who died in 1946) near the former Stone Shed, where the granite blocks for JFK’s gravesite were cut and assembled (on land that no longer belongs to the Foundation). Since the estate once spanned over four thousand acres and has been whittled down to about seven hundred, former parts of the property lie scattered among private hands. Some of these lands include graves. Down the road, the Mellon’s former parcel called Gap Run holds a cemetery with a few marked but mostly unmarked graves, which date to around the nineteenth century and may have included enslaved peoples. At Oak Spring, no human graves are known beyond those buried in Fletcher Cemetery. (The only other known marked and unmarked graves at Oak Spring are for beloved horses and dogs.) Elinor and Nancy have searched whatever attics and basements are accessible through the Oak Spring Garden Foundation with ongoing inquiries elsewhere.

If the memorial wreath was unwittingly left on a sold-off property, in an attic or basement of an outbuilding, it would likely be unrecognizable if someone encountered it. Nancy hypothesizes that, in storage, the wreath would likely be dismantled, resembling a jumble of metal hats, ropes, and branches. Some staff wonder whether it is worth all the trouble to search for when it might be best to “let it lie,” as “some things aren’t meant to be found.”

“It’s like Mrs. had a riddle,” Jay had said on our drive to Arlington. “We may never find an answer for it.”

“Did Mrs. Mellon like riddles?” I asked.

“Oh, yes,” he said in a long and deep Virginia drawl. “Someone may have it and not say anything. Or someone may have destroyed it, God forbid.” He paused. “You just never know. The person who could tell you, she’s not here.”

VI. Wreath

Study sketch of the memorial wreath by Jean Schlumberger, c. 1966–1967. Photographer unknown. Courtesy of the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library Archives.

Rewind to 1966: when John F. Kennedy’s temporary grave hosted a wreath of military hats from the 1963 funeral, awaiting the president’s reinterment in 1967. The caps, periodically replaced from weathering, remained as silent witnesses and sentinels around the Eternal Flame.

In November of 1966, landscape architect Perry Wheeler, who often collaborated with Bunny, was accounted for by Arlington National Cemetery as the “Representative of Mrs. Paul Mellon” to retrieve one set of weathered caps with a key instruction: to be “furnished to Mrs. Paul Mellon, representative of the Kennedy family, to serve as models for commemorative sculptor work for the permanent gravesite.” Around that time, Bunny also made a watercolor sketch for JFK’s grave with notes for the grave to have “a natural wave feeling … giving the overall feeling of the sea. Please cut stone only where necessary.”

A few months earlier, in September 1966, letters between Bunny and Jean “Johnny” Schlumberger hinted at an artistic creation already taking shape. Thereafter, the hats—“caps,” “helmets,” and similar terms—appear in Schlumberger’s sketches and correspondences as a wreath-like sculpture, with references to the president’s grave. Schlumberger’s undated notes describe symbols around the hats—with palm and bamboo signifying JFK’s war service, rope serving for his love for the sea, driftwood-like branches representing his love of nature, a leaf as living hope—all entwining into a memorial wreath.

As JFK’s reinterment approached, plans for the sculpture moved ahead behind the scenes, and Bunny shared Schlumberger’s design with Jackie. Back in 1961, Bunny had enlisted Jackie to support an exhibition of Schlumberger’s jewelry that helped his career, and during the creation of the memorial wreath, Bunny often acted as go-between to move the sculpture project forward. On March 13, 1967, a day before the reinterment, Jackie wrote to Schlumberger expressing her admiration for his drawing. Moved by the beauty of his thoughtful design, which captured such painful loss, Jackie expressed her hope that a maquette of the wreath sculpture might be made for her to consider with Bunny. On the same date, architect John Warnecke wrote to Bunny that JFK’s grave surround should be kept simple: “I am thoroughly convinced nothing should compete with it,” he wrote. “Every flame font or idea of a holder or man-made object that has been tried or suggested by artists, sculptors, and craftsmen have only detracted from the simple beauty or power of the flame.” Warnecke did not seem to be involved in plans for the memorial wreath.

A few days later, on March 17, 1967, Schlumberger’s business partner in New York, Nicolas Bongard, confirmed via telegram his receipt of Schlumberger’s drawing, noting that Louis Féron would make a maquette of the sculpture two times larger than Schlumberger’s design. Féron started to move ahead on the wreath. By June 6 of that year, the sculptor sent a contract to Alfred Fitt (General Counsel of the Army): “In accordance with the instructions of Mrs. Paul Mellon, I confirm to you my understanding of my commission from the Government of the United States of America to develop, sculpture, deliver and install the ‘memorial.’” Féron also sent a copy of the contract to Mrs. Mellon, with a note: “Following the instructions of Mr. Nicolas Bongard, I am sending you herewith two pictures of the maquette [of the sculpture] and two pictures of the sketch drawn by Mr. Jean Schlumberger,” adding “We request your indulgence with respect to the less than high quality of the photographs. The secrecy of the project imposes serious restrictions on us in this area.”

Despite the momentum, the project then stalled. Fitt responded on June 19, 1967, “There remain several major unsettled questions about the design to be used, and consequently you should not proceed at this time with the commission which Mrs. Mellon described to you.”

Not until the following year, after the assassination of Bobby Kennedy in 1968, did plans for JFK’s memorial wreath revive. As Jackie Kennedy collaborated on the planning of her brother-in-law’s grave, she was reminded that she had not finished her husband’s grave. In a letter to Schlumberger, she credited Bunny’s instrumental role in the project and patience through the Kennedy family’s griefs: “If at any time you or Bunny had brought it up again—we were too wounded.” Looking forward, Jackie highlighted how Schlumberger’s “wreath” will “preserve for all time that moment … when his Honor Guard threw their caps around his flame” and when Bobby requested that the hats remain on the grave until they were “crumbling.” In the letter, Jackie formally commissioned Schlumberger’s sculpture and expressed her plan to personally write a history of the sculpture to be framed at the JFK Presidential Library beside the designer’s sketch and legend. She also asked him to include a cornflower in the wreath to commemorate Bunny’s involvement.

By fall of 1968, the project was formally “revived” at Arlington. On October 11, Fitt wrote to Féron asking the sculptor to send a “revised proposal,” per Mrs. Kennedy’s request, and indicated that “Mrs. Mellon will be the agent for securing Mrs. Kennedy’s approval” in “the project to design and install an appropriate adornment for her husband’s grave.” In November, Fitt wrote to Stephen Smith (husband of JFK’s sister, Jean Kennedy) to procure payment for the sculpture from the Kennedy family; Fitt articulated that Louis Féron “is working under an informal commission from Mrs. Mellon on the development of a stone and bronze adornment to be installed on the stone which serves as the flame base,” adding that “Mrs. Mellon would continue to be our contact point for obtaining family approval in matters of style and taste, e.g. stone colors, acceptability of the Féron sculpture, etc.”

Féron proceeded on the model, so by early 1969, Schlumberger and Bongard visited Féron’s studio in New Hampshire to see the plaster model of the wreath. Archived photographs show them viewing the plaster wreath entwined with actual hats. As spring turned to summer, receipts from the Modern Art Foundry in New York confirmed that a “memorial wreath” was “cast and finished” in bronze and shipped to Féron. The sculpture was essentially finished.

But obstacles arose, and the project stalled again. Despite the sculpture being “cast and finished,” it was not mounted nor installed at the gravesite. In February 1970, Schlumberger wrote to Bunny with urgency, pressing her “to act on the Kennedy side, or McNamara, in order to get a prompt decision on the monument, in order that Féron, who holds the secret of his mounting” can proceed “before it becomes too late.” In May 1970, Jackie wrote to Schlumberger about “complications” at Arlington Cemetery, with hopes to know more by fall. Thereafter, references to the sculpture retreat from archival records.

Whether due to “the secrecy of the project,” the heavy aesthetics of the bronze wreath of hats, their frought symbolism that may have seemed outdated by the tumultuous national and personal events of the era, or something else, the sculpture at some point went missing. It was never installed on JFK’s gravesite. Jackie never wrote a history of the memorial wreath, and Schlumberger’s drawings were not displayed at the JFK Presidential Library. Few people knew about the project, so the sculpture’s disappearance didn’t receive any public attention.

Like the form of the sculpture itself, the story of the memorial wreath comes in pieces. Interlinking parts raise questions not only around what is missing but also what may yet be found. As the sculpture came apart, Féron essentially held the key for how to put it together. If the memorial wreath still exists, whoever has it (boxed in a crate or even just a part) may not know what they have. But more: even if the sculpture is recognized in a disassembled state, those who rediscover it may not know how to piece it together again.

I ask Nancy and Elinor why they want to find a half-century-old sculpture, in the face of the pandemic and so many other pressing current events in the world.

“To us, it matters,” Nancy says. “The affection between Bunny and Schlumberger—they inspired each other. They talked about it for five years. They executed it. It is a piece of art with a history behind it. It should be given some homage.”

“Does it matter to the world?” Elinor conjectures and sighs, “No.” She continues, “Does it matter if it is found? Yes! Why does it matter?” She laughs. “Because I don’t want to waste a year of my life!” More seriously, she says, “Either we have a story to tell and don’t have an ending—and it could be that nobody knows—or, someone reads this story and says, I have that—even if they’re using it as something else, it could be out there.”

Elinor mentions that, in speaking with stonemason Tommy Reed, she learned that pink granite from the Kennedy grave project still existed at Oak Spring. Enough stone remained to make a new bench—and “a bench” had been noted amid unrealized plans for the gravesite. Tommy made that new bench, which now sits outside of Bunny’s house garden as a quiet place for contemplation.

“Somebody could have only a piece of it,” Nancy says of the missing sculpture. Its pieces may be distributed and not stored together. Since the existence of the sculpture wasn’t publicly known, few may recognize its value if found. She relays the recent rediscovery of a long-lost sculpture being used as a lawn ornament in Missouri; a curator drove by and recognized its creator as William Edmundson (a Black folk artist and tombstone carver, who was buried in an unmarked grave; Bunny had one of his sculptures outside her library). “Who does it belong to now?” Nancy asks of JFK’s memorial wreath. “Even if the sculpture didn’t make the cut” and ended as runner-up to the simplicity of the Eternal Flame burning alone, Nancy says, “it is important because it is a piece of history.”

“Somebody knows where the sculpture is,” Elinor says. Most of JFK’s peers have died. Those who are left are in the final years of their lives. “Maybe they can tell us before they die.”

VII. Correspondence

Left: Jean Schlumberger with a plaster model of the sculpture with hats in the studio of Louis Féron. (Photo included in letter from Schlumberger to Bunny Mellon, February 1969.) Courtesy of Oak Spring Garden Foundation. Right: Louis Féron and wife, Leslie Snow, with pieces of a wreath sculpture, May 1969. Photograph by Evelyn Hofer, courtesy of estate of Evelyn Hofer.

One afternoon, in the Oak Spring Garden Library, Nancy reads to me excerpts of letters to Bunny from Jean Schlumberger. I had asked if she could share some of the designer’s relevant correspondences, so she digs into the archives to find those referring to JFK’s gravesite and finds a quiet place where she can read them aloud to me.

We sit in the library’s upper drawing room. In an upholstered chair, Nancy holds airmail envelopes with bright postmarked stamps and delicate handwriting. At times, she refers to Schlumberger as “Johnny,” even though she never met him. The voiced familiarity echoes stories she likely heard at Bunny’s side. The library vault holds letters that Schlumberger sent to Bunny but little of what Bunny sent him. These envelopes are tied with a soft cord, out of order, as one might keep letters shuffled in a drawer. Nancy gives me permission to transcribe what she reads aloud, out of order but dated; I later reorder them chronologically and she checks my transcriptions:

1967, no specified month (likely beginning of the year, addressed to Bunny’s wintering ground in Antigua from Schlumberger’s home in Guadalupe):

Now I am very very well and have been working very hard on the president’s grave … it is a great hope to get it out of the usual look of those bronze sculptures—its [sic] got to be moving and understandable but not too realistic. The hats have been a great help there on the floor in the studio—keeping the silent watch they started on that fateful day—reminding me too—constantly—that this has to be filled with tenderness, love and emotion—

February 19, 1967:

Having finished this afternoon the “President’s tomb” after four weeks of work … do hope I won’t disappoint you and Jackie and the country to which we owe that great message[.]

March 16, 1967:

I thought of you both but so much on the night of the fourteenth in Arlington, it must have been so moving, so terribly emotional, almost to the point of being unbearable. I am so happy that Jackie liked the drawing and understood the symbols, the meaning and the message of hope I tried to convey through it—. Now, and this is not the least of the task, we have to make it.

April 20, 1967:

Thank you also for the very moving description of your trip with Jackie to Arlington at night and in the early morning—.

August 7, 1968:

I shall write to Jackie through you to thank her for her telephone call and what it meant—you had given me the joy the day before and she confirmed it in her own words the next day. I love the idea that we are all giving in the purest sense of the word—with no interest attached to it—but to built [sic] a monument to the hope that millions and millions of people had put in an ideal—

January 7, 1969:

I am flying back to New York to go to Portland to supervise, on the 23rd and 24th, once more the work of Féron on the President’s tomb—

February 15, 1969 (the letter does not mention the memorial project but includes a photograph of Schlumberger viewing a plastered wreath of entwined hats in Féron’s studio in New Hampshire).

October 29, 1969:

I should have asked you yesterday, if it was possible to take up with Jackie the idea of setting the tomb at Arlington for the anniversary of the 22nd of November—. I am sure Féron could do it in a few days and it seems to me that it would be an occasion which would make sense, in the public’s mind—.

February 2, 1969 + 1 = 1970:

On the other hand, if you could act on the Kennedy side, or McNamara, in order to get a prompt decision on the monument, in order that Féron, who holds the secret of his mounting, could do it before it becomes too late—that would be a good idea!

As an essentially one-sided conversation, Schlumberger’s letters between 1967 and 1970 reveal the memorial wreath progressing in fits and starts, with delays and complications, foreshadowing the sculpture’s fate. The library does have a letter that Bunny wrote to Schlumberger (dated April 1, 1967), wherein she describes JFK’s reinterment ceremony in heavy rain, standing beside Jackie for the short ceremony, brother Ted Kennedy’s admiration of the grave that resembled a “break water into the sea,” and Bunny’s wish to share this all with Schlumberger. Pulsing at the heart of these correspondences is the intimate friendship between Bunny and Schlumberger, the loyalty of their creative collaboration, his sincerity to not “disappoint you and Jackie and the country,” and his increasing tone of urgency to mount the sculpture “before it is too late.”

In the years after JFK’s 1967 reinterment, national and international events pressed in and likely contributed to delays related to the memorial wreath. In April 1968 came the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. (Bunny and Jackie attended the funeral together) and, in June, the assassination of Senator Robert Kennedy. While Bobby had expressed concern about representing military hats at his brother’s grave amid rising antiwar sentiments, public divisions across the country had escalated with the Vietnam War, the Cold War, the Civil Rights Movement, environmental issues, poverty, and other concerns that left the country increasingly fractured. Even as Bobby’s death led Jackie and Bunny to resurrect the making of the memorial wreath, personal events took precedence. In October 1968, Jackie married shipping magnet Aristotle Onassis and moved to Greece, concerned for her children’s safety after the Kennedy assassinations. The Mellon family also experienced deaths during these years, including Paul’s sister Ailsa in 1969, after Ailsa’s daughter and son-in-law were declared dead after their plane disappeared in 1967, the same year Bunny’s father died.

Interpersonal tensions may also have affected the wreath’s history. According to Bunny’s biographer, Meryl Gordon, after Schlumberger had a stroke in 1974 that rendered him unable to draw, he “confided to friends that Bunny had dropped him” (they later reconciled). In June 1977, the International Herald Tribune published an article wherein the artist commented, “Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis … isn’t rich enough to be one”—that is, a customer of his jewelry. But that year lies ahead of our story of the memorial wreath, when the artwork was made and when it went missing.

Nancy and Elinor point me to the exhibit on Schlumberger that they curated in the Oak Spring Gallery in 2020. The exhibit comprises a small room of wall panels and reproduced photographs, encircling the original greenhouse finial that he designed, cast in lead by Robert Bradford and recently conserved. A placard quotes letters from Schlumberger to Bunny, including one that Elinor and Nancy believe may be the earliest reference to the memorial wreath, albeit unnamed:

September 15, 1966 (from Schlumberger in Hong Kong to Bunny at Oak Spring):

Your idea was so exciting the other night, that I couldn’t sleep—so many questions left without answers—but the mere fact, that we are sharing something together in a new creative experience is of a great stimulation. I cannot tell you how much it is the sort of thing I needed at the moment—and I cannot thank you enough your guiding hand which is leading me further and further.

When I later thumb through a catalogue from another exhibition of Schlumberger’s jewelry and compare it to his archived sketches of the memorial wreath, some of his surreal necklaces and charm bracelets resemble small wreaths. In kind, JFK’s memorial wreath resembles a necklace or bracelet for a grave. Schlumberger’s jewelry designs often fit complex parts together, which is echoed in Féron’s sculpture of the wreath—not cast as a single piece but as multiple parts—separate and needing to be interlinked.

Amid Bunny’s botanical books and art in the Oak Spring Library, as Nancy reads aloud archived letters, she is visibly moved. She stops and looks at me. “They worry about each other,” Nancy says tenderly, shaking her head. “Bunny knows how he [Schlumberger] works. He puts everything into it. She works the same way. She loves Schlumberger. She loves Jackie.” At one point, her eyes water. “I don’t know why I’m crying,” she says. “They put all of this work into it, and then it doesn’t happen.” Later, she confides about Bunny: “I didn’t ask questions. It wasn’t my place. If she asked my opinion, I would give it—but I didn’t ask questions.” She pauses. “If I knew then what I know now, I would have asked.”

VIII. Remains

Nancy Collins hanging holiday wreath on headstone of Rachel “Bunny” Lambert Mellon, in Trinity Episcopal Church Cemetery, Upperville, VA. Photo by G. E. Henderson, December 2021.

In addition to Arlington National Cemetery and Fletcher Cemetery, a third graveyard in Virginia relates to this mystery. Not far from the Oak Spring Garden Foundation, in the town of Upperville, stands a parish called Trinity Episcopal Church. The medieval-styled bell tower and steeple of Trinity seem transplanted from the French countryside to the hollows of the Blue Ridge Mountains.

Founded in 1842, the church grounds transformed between 1951 and 1960 through the support of parishioners Paul and Bunny Mellon, who donated thirty-five acres of land and underwrote the renovation by architect H. Page Cross. Largely influenced by Bunny, this transformation of the buildings and surrounding grounds included the church’s cemetery in the decade immediately preceding her work on JFK’s gravesite.

Behind the rebuilt church now sits the Mellon family plot, hemmed in by a stacked stone wall. A few decades after the church renovation, in 1996, Paul and Bunny moved the Mellon family graves from Oak Spring’s Fletcher Cemetery for reinterment at Trinity. The Mellons’ slate headstones stand simply, inscribed by the Benson family, the same New England stone carvers who etched JFK’s gravesite. Other connections exist with the presidential grave at Arlington National Cemetery, since W. J. Hanback, the contractor on the 1950s Trinity Church renovation project, also worked on JFK’s gravesite.

When Bunny was alive, she regularly visited the Mellon family graves at Trinity Church Cemetery, just as she occasionally brought flowers to the Kennedy plot at Arlington National Cemetery, where Jackie was buried after dying from cancer in 1994. Since Bunny’s death in 2014, at the age of 103, Nancy has delivered weekly bouquets (handmade by Oak Spring’s gardeners) to Mr. and Mrs. Mellon’s graves. OSGF supports this weekly delivery by someone who knew Bunny personally. (Neither Elinor nor Peter Crane ever met the Mellons.) On the first Friday of each December, Nancy switches to a seasonal offering of handmade wreaths.

When I learn of this holiday ritual, which coincides with my visit, I ask to join Nancy for her laying of wreaths at the Mellon graves to see how Bunny designed her own burial plot. Our visit to Trinity Church Cemetery offers a glimpse of Bunny’s relationship with death: a sensibility that to some degree must have influenced her planning of JFK’s gravesite.

The morning of our winter pilgrimage is crisp and overcast. Another guest at Oak Spring, visiting from Austria, joins our short drive to Upperville. The town is a veritable village spread along a two-lane highway, marked by historic homes with a pub called Hunter’s Head, a hardware store, gourmet market, post office, and little stone library the size of a bus stop. Trinity Episcopal Church is a defining feature amid rolling hills of Civil War battlefields, equestrian grounds, and gentlemen farms turned vineyards. Out of sight lie quiet reminders of the area’s proximity to the nation’s capital, including Mt. Weather (a site for government relocation in case of national emergency) and the Mellons’ personal bomb shelter (built during the Cold War, underground and invisible compared to their private airstrip, which can be seen from the sky).

Nancy guides us around Trinity Church’s cobbled and planted grounds into the sandstone sanctuary. A stained-glass window hosts a luminous oak, echoing Bunny’s insignia on letterheads and linens. Bunny’s influence inscribes wooden pews and stone beams with vegetal, floral, and animal motifs, detailed as a carved hive of bees. Windows douse the sanctuary with light, evoking her library’s gilded Books of Hours.

Listening to the silences between Nancy’s respectful reminiscences of her patron’s public and private life, I weigh varied characterizations of the woman at the center of this story: a shadow who slips in and out of view. (Bunny’s mantra was “Nothing should be noticed,” as she famously told the New York Times in a rare 1969 interview.) A table at the back holds service bulletins and religious ephemera, including a pamphlet of daily contemplations. I open randomly to a page with a vignette mentioning the children’s classic, The Runaway Bunny. The title seems apropos for our visit.

Outside, behind the church, low walls of stacked stones crisscross a lawn leading to the Mellons’ semi-enclosure. Framed by stone, the plot feels like an intimate room, with a bench to the side. Over the headstones, red hawthorn berries cluster on bare branches. Dry, fallen leaves litter the ground. Ivy creeps over the stone walls. One of Bunny’s beloved hardy orange trees greens a corner. Amid evergreen boxwood, Nancy admires the “bones of the garden in winter” and says that for Bunny, “nature was her church.”

Like other cemeteries originating in the nineteenth century (when graveyards shifted from death-fearing thresholds to contemplative parks), the Mellons’ burial plot echoes “a garden of the dead.” The front row of the Mellon plot includes Bunny and her two children from her first marriage: daughter Eliza Lloyd Moore (1942–2008) and son Stacy Barcroft Lloyd III (1936–2017). In the back row lie the remains of Paul Mellon (1907–1999), his first wife Mary Conover Mellon (1904–1946), sister Ailsa Mellon Bruce (1901–1969), and parents Andrew William Mellon (1855–1937) and Nora McMullen Mellon (1878–1973). Space remains for future family members, if they choose.

The first grave upon entering the enclosure is Bunny’s. I remember reading that she chose to be buried not in her signature fashion, designed by the likes of Hubert de Givenchy or Cristóbal Balenciaga, but in a graduation gown dating from her receipt of an honorary degree from the Rhode Island School of Design.

“That’s my girl,” says Nancy as she tethers the wreath to the headstone. “The gardening girls made these beautiful wreaths for you,” she addresses the stone, then turns to me. “She didn’t want to be back in the shade but out in the light. I come here and sit and tell Mrs. what’s going on at the farm. I asked her the other day to help us find the Schlumberger,” she says, referring to the wreath.

There is an authenticity to Nancy’s call-sans-response, as she says Bunny “respected and honored the dead.” Earlier in the week, during our visit to Arlington, Nancy had appealed to the Kennedy graves, whispering, “We’re friends of Bunny’s. Help us find the Schlumberger.”

“Eliza, you’re next,” she says now, heading toward the headstone of Bunny’s daughter. It is etched with an excerpt from Eliza’s sketchbook that begins, “The more I pursue, the more I see—” Placing the wreath, Nancy voices a simple question to the stone: “How did that happen to you?” After Eliza died in 2008, Bunny and Nancy would come to sit on the bench and visit her grave, and whenever the pair drove past Trinity Church Cemetery, Bunny would wave through the car window and voice greetings to her predeceased daughter.

On this wintry day, the air is chilly. Nancy works efficiently around the graves. It does not take long to hang the evergreen wreaths. She stands back to look at the grouping. “You guys are all dressed for Christmas,” she says to the headstones. “Everyone looks so pretty.”

Nancy has worked almost three decades at Oak Spring, overlapping with the last decades of Bunny’s life. As a nurse-turned-archivist, she attests to the fact that Bunny knew “all the greats” of the twentieth century, yet “her farm help was like her family.” Bunny bequeathed Nancy a house at Rokeby Farm for her lifetime, a privilege granted to a very few staff who worked particularly close to the Mellons. Like other staff who signed a nondisclosure agreement, Nancy has been given some dispensation to share, but she says, “The rest I will take to my grave. It was beautiful to be part of.” Gazing somberly at the gravestones, she says, “Who’s going to take care of them after I’m gone?”

Even after her death, Bunny’s remaining legacy staff work to bring her intensions to life. Back at Oak Spring, when Tommy Reed describes his work as a stonemason at Oak Spring for a near half-century—from the maquette in Fletcher Cemetery, to the stacked stone walls, to walkways and patios around the garden and the library, and almost anything else with stone—he repeats what Mrs. Mellon told him. “You are my hands,” she would say. “You know what I want.” He reminisces, “Me and her kind of grew together.” The arborist, Clif Brown, says something similar about his tree pruning as arboreal sculpting: “You are my hands,” Bunny would tell him. “You are my eyes.” (Her vision declined late in life.) As Bunny’s estate has transitioned into the Oak Spring Garden Foundation, aimed increasingly toward efforts around environmental stewardship, her sensibility is kept alive by those staff who continue to uphold “the Mellon way.” Year by year, fewer staff who worked directly with the Mellons remain with OSGF, and those who did distil their presence like a tincture.

“She never did say why she left it here,” Tommy says of the oyster stone maquette. When we meet at Fletcher Cemetery, he tries to recall a half-century ago, shaking his head. “I was a kid when I put this together.” He describes how the Mellons “wanted to set some artifacts on it” to weather and age, appearing like tangled metal branches and helmets. As we talk, he pulls up a piece of the oyster stone, and his gnarled fingers curl around the crumbling maquette. “See, it’s real soft, real brittle.” He breaks it easily. “In some pieces, you can see shells. If you were to take it up now, it would just deteriorate.” He drops the stone fragments and shakes his head, mentioning that the metal artifact stayed for only a short time. “It was all hush hush. They didn’t want no pictures taken. They didn’t want no grass interrupted.” For projects constructed on the property, it was normal for staff to lay plywood on the ground in order to keep from disturbing the grass. Tommy would rake or sweep away imprints, “as if they had never been there.”

Bunny did everything with precision, to the point that if she asked Tommy to build a stacked stone wall, then changed her mind about its placement (even by just a few feet), she would have him dismantle the entire thing and start all over again. “To get it right,” Nancy says, “and she was right.”

It is hard for me to fathom how a woman with such precise taste and more-than-ample resources would leave a crumbling stone maquette in plain sight if she had wanted it gone. She had all the means to make something go away. While she favored imperfections (coordinating cracks in stones through which plants could grow, for instance), such details did not stand apart but grew inseparable from the whole. She was a complex figure and not uncontroversial. If this stone maquette could talk, I wonder what it would say. The stone sits testifying silently to its shadowy origins, seasonally covered by fallen leaves, snow, or budding snowdrops. The fact that Bunny did not remove it from Fletcher Cemetery left open the chance that someone, decades later—namely, Elinor Crane—might eventually ask about its purpose, attempt to remember its history, and want this story told.

For Elinor, the story feels important, almost personal, as JFK’s assassination rocked the world at the time. Most people alive during JFK’s presidency remember where they were when they heard the news of his shooting and death. Elinor was nearly three, too young to remember, but carries her family’s memories from their home outside Chicago. Elinor’s siblings remember her mother weeping while ironing and watching television coverage. Not long before, her older brother had been reading about the assassination of Abraham Lincoln with their father, and he recounts to Elinor that “here we were, living another assassination ninety-eight years later … astounding to us … Unreal.” Others I’ve asked who lived through that time describe it as the defining moment of their generation, using words beyond “shock,” “stunned” and “grieved”: “The world stopped.”

Focusing on historic conservation for future generations, librarian Tony Willis now wonders whether the stone maquette in Fletcher Cemetery should be preserved as a stand-in for the missing memorial wreath. From an archival perspective, he wonders if OSGF should protect the stone maquette or at least slow the process of its deterioration. I wonder about this alongside alternative approaches. If the stone maquette were left to weather and age, it might even “crumble to dust” (akin to Bobby Kennedy’s wish for the original hats on JFK’s grave) as an ecological approach for its future.

Considering how Arlington National Cemetery, Fletcher Cemetery, and Trinity Episcopal Church Cemetery all interrelate, the story of JFK’s memorial wreath seems to be about more than a missing artwork, or the philanthropic gardener and the jewelry designer who catalyzed its creation—or even a fallen president. The story of the missing wreath is also about what and who gets remembered and forgotten in retellings of history. Loss is never about something or someone in isolation but in relation. Attempting to find an artwork, missing for over half a century, bears a responsibility to not only the lost object but also the space left behind. The very act of searching grows into the gaps of history—who tells that story and how it is told.

IX: Lost and Found

Cast and assembled memorial wreath for JFK’s gravesite, unknown location and date, photographer unknown. Photo acquired in 2021 by OSGF from an eBay sale of unidentified photos of “War Art Work” by Louis Féron (from the 2018 estate sale of Louis Féron and Leslie Snow). Courtesy of Oak Spring Garden Foundation.

In recent decades, many lost artifacts around the world have been found. This seems to be an era of lost-and-found art. Restitution efforts have recovered art stolen by the Nazis from Jewish families in the Holocaust. Virtual preservation has engaged augmented reality to scan threatened archeological sites and artifacts in order to recreate projections like Palmyra and the Buddhas of Bamiyan, otherwise destroyed by wars in Syria and Afghanistan. Detective hunts have ensued in pursuit of heisted artworks, including Willem de Kooning’s Woman-Ochre that fortuitously made its way back to the University of Arizona Museum of Art, even as a medley of works stolen from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum remain an unsolved mystery. Formalized efforts in repatriation have enabled the return of artifacts across national boundaries. Attention to materiality has led art historians to understand how metalworks were melted and refashioned and how painted-over canvases carry layered images beneath their surfaces. Eroded land art, such as Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty (1970), defaults into a barometer for climate change. A collection of lost art has even been reimagined into a curated Impossible Museum—in which JFK’s missing memorial wreath would aptly fit.

All of this begs the question: why this interest, and why now?

To frame the story of JFK’s memorial wreath as a lost object suggests that the desired conclusion of this essay rests on it being found. And to some extent, that has been the point of this exercise. To find the missing artwork seems the logical conclusion for this story—which indeed has a plausible ending, since evidence suggests not only that JFK’s memorial wreath was made but also that there are many possible reasons why it may have been lost. The wreath’s military symbolism may have grown out of step with growing public antiwar sentiment during the Vietnam War. Reasons may have been more personal, as Jackie Kennedy tried to move beyond her public tragedies of the 1960s. Or the sculpture’s executed design may have been deemed aesthetically too heavy by those who commissioned it, as the timeless simplicity of the Eternal Flame made a stronger statement than any adornment. There may have been additional reasons, and future historians may follow these like a passed torch: from Arlington National Cemetery’s recent conflicted history, which included the mishandling of grave matters, to dusty crates that simply remain unopened on a sold-off Mellon property, to something else to be explored. The memorial wreath may have been lost through a combination of these reasons, or due to none of them at all. What is known is that the artwork was made, went missing, and remains lost to this day.