The Crush Problem

In my last post, I wrote about the Lonesome Dove Problem—i.e., my lifelong struggle to find a girthy novel as totally absorbing as Larry McMurtry’s masterpiece—and attempted to identify some common denominators shared by Lonesome Dove and a few other totally absorbing novels, so that I might be better equipped to analyze future selections based on their potential Lonesome Dove-esque-ness.

In the process of addressing the Lonesome Dove Problem, however, I realized that I have other Problems—i.e., other books or groups of books which, for seemingly inane reasons, I’ve elevated onto impossibly specific pedestals that inherently resist new entries (see also: “Lonesome Dove-esque-ness”). Which brings me to…

The Crush Problem.

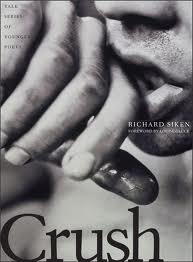

It’s lucky that Crush, Richard Siken’s Yale Younger Poets Award-winning first collection, is so much shorter than Lonesome Dove, because I literally carried Crush everywhere I went for three or four years. It was like my poetry-security blanket. Which is funny, because Crush offers little security—in fact, it totally upended my entire aesthetic sense of self as both a reader and a writer.

Before Crush, I was afraid of messy poems. I liked my poems short n’ sweet n’ clever, with last lines that tied everything up in neat little bows, almost like punch lines.

But the poems in Crush are decidedly, unapologetically messy. They hurtle; they sprawl. They end awkwardly. They blurt out their secrets. After I read Crush, everything else felt limp, stale, tame.

“Fine,” you might proffer (oh good, you’re back!). “Just look for more messy poems!”

For a while, I did look—that is, I flipped through poetry collections to get a visual sense of their messiness. But just because a poet hits the “tab” key a lot doesn’t ensure a Crush-worthy collection. The engine driving Siken’s messy passion, it seems, isn’t purely visual.

Just when I’d given up all hope of ever being Crushed again, I happened upon Jericho Brown’s Please.

Brown’s poems aren’t nearly as messy as Siken’s, nor is he quite so monomaniacal; while Siken kind of goes zero-to-sixty from “I love you” to “OH MY GOD IF THERE EVEN IS A GOD WE’RE ALL GOING TO DIE,” Brown offers nuanced musings not only on sex and relationships but also on music, form, family, race, and history.

But my response to Please was immediate and visceral, and immediately, viscerally reminiscent of my reaction to Crush.

“The common denominator here is obvious,” you might point out, smugly. “You have a Gay Male Poets Who Title Their Collections With Single Words That Could Be Interpreted As Multiple Parts of Speech and Whose Cover Art Features A Close-Up Photograph of a Stubbled Chin Problem:”

Aha! Problem solved!

No, wait.

Exhibit B: a disproportionate number of my favorite single poems are also authored by gay men. Gay men whose collection titles have more than one word, and whose cover art is 100% chin-free. The heteros, the lesbos, the variably conflicted and confused—no other orientation is half as well represented in my personal canon.

But before we dig into that canon, a few caveats:

First and foremost, I’m not claiming that “all gay male poets,” let alone “all gay men,” share the same preoccupations and quirks. That would be ridiculous, especially since I’m quoting only from contemporary gay male poets I know and love—an extremely incomplete list.

Second and secondmost, I’m also not aiming to make a comprehensive list of said preoccupations and quirks—not even for the specific gay male poets I cite.

Third and thirdmost, I’m aware that my observations may be informed by my own stereotypes and presumptions, though I certainly do my best to avoid this.

In other words, I’m just taking a first stab at answering those potentially Problem-solving questions: What do these things have in common? Why do I love them so much? And how can I find more like them?

“OK, OK,” you might backpedal, exasperatedly. “Just get to the poems.”

Finally! In vaguely associative order, and with a fair amount of overlap between observational categories, here’s what these poems have in common.

• Blurred boundaries between violence and tenderness. Some of these poems like it rough. Some of them wish they didn’t. Some of them get too rough, and then they’re not sure if they like it. Or sometimes they don’t like it rough, but rough is the only way they seem able to find it.

How the hell you say

But I love you.

Though I’d rather hear,

Fireplace. How to burn you

Alive. How to keep my man

Warm.

(Jericho Brown, David)///

He hits you and he hits you and he hits you.

Desire driving his hands right into your body.

Hush, my sweet. These tornadoes are for you.

You wanted to think of yourself as someone who did these kinds

of things.

You wanted to be in love

and he happened to get in the way.

(Richard Siken, A Primer for the Small Weird Loves)

• On a related note, penetration. Which, in these poems, often feels more like permeation (as in penetration that diffuses, infuses, spreads) or breach (as in, of boundaries, of defenses):

Everyone needs a place. It shouldn’t be inside someone else.

(Siken, Detail of the Woods)///

That part about the body

asking for it,to be broken into—is that the first, or the last part?

(Carl Phillips, Mirror, Window, Mirror)///

Here is the cake, and here is the fork, and here’s

the desire to put it inside us, and then the question

behind every question: What happens next?

The way you slam your body into mine reminds me

I’m alive, but monsters are always hungry, darling…

(Siken, Snow and Dirty Rain)

• On a related note, complex power dynamics. Sure, some of these poems are pretty explicitly about BDSM and related activities. But the language of power is applied outside the bedroom/dungeon, too, creating an atmosphere in which intimacy involves constant negotiation of control—who has it, who wants it, who takes it, who wants to give it up.

You say, Don’t wreck me, and I say I won’t, but how can I know that?

To see a man in shackles, how you feel about that, depends on whether the servitude is voluntary.

(Mark Wunderlich, Voluntary Servitude)///

…I wish you would

Sniff a man. I wish his whipSharper than fangs. I wish you could know

How bite-less I feel, the mouthI don’t close, his head in my throat.

(Jericho Brown, Lion)

• The unshakable presence of death. The sex/death connection is hardly revolutionary (see also: la petit mort). But death feels especially present in these poems—sometimes spectral, sometimes explicit, but often inextricably tied to sex and desire. Taken together, these lines suggest a world in which intimacy can be contagious, toxic, risky.

I live with

A disease instead of a lover.

We take turns doing bad thingsTo my body.

(Brown, Contrast)///

…Erotica,

give it up and let

me have my way. And the gin-soaked dread

that an acronym was festering inside.

(Randall Mann, Fall of 1992)///

You are a fever I am learning to live with.

(Siken, Straw House, Straw Dog)///

isn’t he the one who looked upward into your gawp as if a deathbed held him against you. he was living, then. you were both living

and the vessel protruded, your hull dragging up onto the beach, his carcass already a carcass on the sand, no, he was a darling critter

a feral thing, but he struck you, he bit you, and you broke inside and the condom broke, shoddy piece, princeling, posturer, dirty dirty beast

(D.A. Powell, Centerfold)

OK, so maybe this isn’t really that much of a Problem. After all, there are more gay male poets than Lonesome Doves. But perhaps this analysis still yields some insight into what it is that I look for in poetry, regardless of its Crush-esque-ness. Urgency. Avoidance of sentimentality. Unexpected tenderness. Complex dynamics. Palpable heat.

Or, as Siken writes:

…the gentleness that comes,

not from the absence of violence, but despite

the abundance of it.

Then again, I hesitate to end by praising these poems for their universality. I remember reading various rave reviews of Brokeback Mountain (screenplay by Larry McMurtry, holy full circle!), which repeatedly praised the film as “a love story for everyone.” The highest accolade available to a gay movie, it seemed, was, “Don’t worry—it’s not a gay movie.”

But Brokeback Mountain is a deeply gay movie, about the specifically gay phenomenon of the closet, without which Ennis and Jack would presumably have come down off the mountain and lived happily ever after.

And my gut tells me there is something, well, gay about these poems—something that doesn’t preclude their universality, but that also distinguishes them from their hetero/lesbo/etc counterparts.

What do you guys think? Are gay male poets especially adept at stuff like urgency, unexpected tenderness, heat, etc? If so, why?