Snappy Answers to Stupid Questions

“Oh, I get it. ‘Pete’ is the name of the boy who falls off the log. ‘Repeat’ is the name of the other boy, but when you say his name, you’re also asking me to say the joke again.”

My daughter says this a week after she’s been told the classic “Pete and Repeat” joke. You know this, right?

Joker: “Pete and Repeat sat on a log. Pete fell off. Who was left?”

Rube: “Repeat.”

Joker: “Okay, Pete and Repeat sat on a log…”

For days, my daughter has told this joke to anyone within earshot. Now, for the first time, she actually understands it.

“That is kind of funny,” she says.

I agree. I taught her the joke, which I’d forgotten until I unearthed my copy of Tomfoolery: Trickery and Foolery with Words by Alvin Schwartz. Culled from a century of American folk humor, the book’s chestnuts range from droll to vaudevillian. Often, the book instructs you to injure your friends. These jokes are decidedly not-nice. Some are even a little wicked—the literary equivalent of Wile E. Coyote catching fire, or, if this reference is lost on you, Ren slapping Stimpy, or a Minion saying “bottom.”

But my daughter’s slow-uptake reminds me of myself at her age—knowing that words or pokes are supposed to be funny, but not understanding why. As she reads, she stumbles over references to a daily life that looks nothing like her own: Finns fighting Russians, trains and harbors, rotary dials, Prince Albert in a Can. (Honestly, what is Prince Albert in a Can?) All the same, she’s riveted. And she’s more than ready to try her jokes on all of us.

This makes me wonder: why? If we don’t get the joke, why read it—or tell it? What could possibly be the pleasure? For snappy answers, of course, I turn to the books I loved most, but understood least, as a child: my collection of Mad Magazine paperbacks.

What, Me Worry?

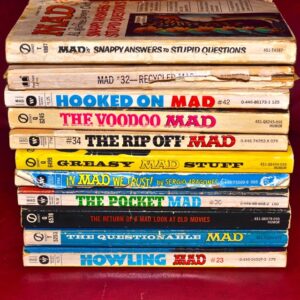

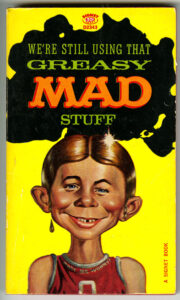

Mad magazine paperbacks consumed hours of my grade school attention. My collection—about 30 books— was inherited from a number of older boys.

A side note: Recently, on the first day of my humor-themed literature class, when asked what made them laugh, student after student said, apologetically, “I have the sense of humor of a twelve year old boy.”

“Why are we apologizing?” I asked. “And why do only twelve year-old boys get to laugh at gross, obnoxious things?”

Since the semester just started, we’re still getting to the bottom of it (heh, heh, bottom). But (heh, heh, but) my students’ confessions remind me that even as a child, I knew there was something rude about my favorite books. They were not a joy I disclosed. As a kid, and as a girl in particular, reading my stack of Mad Magazine paperbacks felt sneaky. Like I was getting away with something. Like a hobby not to mention at slumber parties.

Of course, bucking the social order is the point of Mad, which parodied everything from advertisements to politics to family relationships to movies. No target was safe, not even Mad books themselves (which were “garbage”) or their readers (who were “clods” and “idiots”). Every grandiose plan of the status-seeking was punctured by the pens of cartoonists Don Martin and Sergio Aragonés. Even stealth could get you blown to bits, as I learned from “Spy Vs. Spy.”

The Lighter Side Of…I’m Not Exactly Sure

Passed through generations of boys, originally published in 1950s and 60s, the books were, frankly, puzzling. For example, the opening piece of 1959’s The Voodoo Mad describes “How To Be a Mad Non-Conformist.” In a nutshell:

- Conformists wear glasses and smoke pipes, enjoy “Technicolor movies,” and “read banal best-sellers.”

- Ordinary Nonconformists play bongos, grow beards, and read “boring literary journals.”

- Mad Nonconformists wear pith helmets and opera capes and read “the Roller Derby News.”

What did any of this mean to me, a child of the 1970s and 80s? What was a Roller Derby, or, for that matter, a literary journal? What was the John Birch Society? Why was everyone so irritated by teen-agers? Was it really so easy for women to lose their bikini tops? According to Mad, book clubs were for men and bridge clubs were for women. Writers were unhappy. Married people were miserable. Hippies were smelly. Celebrities were shallow and infinitely mockable, particularly someone named Mickey Rooney and a couple named Liz & Dick.

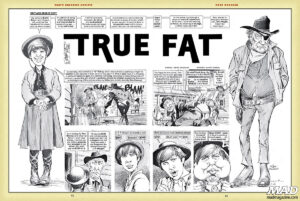

I didn’t understand much of what I read. And I certainly didn’t seek the answers from my parents or librarians. Instead, I studied the parodies of movies I’d never seen and signed membership cards to fake clubs. I played along. I’m pretty sure that my first act of literary interpretation—poring over lines and images, comparing parts of texts, digging deep—began with Mort Drucker’s parody of the 1969 movie “True Grit.”

As a reader, Mad paperbacks taught me how to be patient and dogged with a text. (Of course, pictures of half-naked people always helped.) When confronted with references beyond comprehension—when I could have shut the book—I stuck around because I wanted to get the joke.

The Shadow Knows

Somewhere along the way, those books also shaped me as a writer. Not that I’m aiming for lots of laughs; in fact, my characters are usually in despair. Likewise, the targets of Mad’s satire were often dark: advertisers, war-mongers, the trappings of shallow consumer culture. I couldn’t have named it in those terms, but even as a child, I understood that shiny surfaces were never all they seemed.

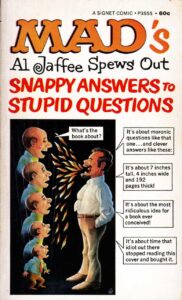

I also learned about narrative structure and economy—that on the page, it’s best to make an impact quickly. After all, a joke relies on the unexpected turn—the joker leads you in, makes you comfortable, and then zing! A gorilla jumps out! Sometimes, the zingers were spoken. Following Al Jaffee’s “Snappy Answers to Stupid Questions,” I could script exits to possible conflicts.

For example, if I ever got drenched in the rain on the way home from school, Jaffee provided my list of comebacks:

Stupid Question: “Is it raining?”

Snappy Answer 1: “No, I rode home in a water truck.”

Snappy Answer 2: “No I’m practicing to be a water sprinkler.”

Snappy Answer 3: “No, I’m drenched with liquid sunshine.”

What power for a shy, short girl to imagine: turning words into cartoon wallop, something stinging and impressive. Except I’d never really say something like that out loud; if I did, I’d probably whisper.

Instead, my shadow waged all my battles with the world. As a good kid, and as an emerging writer, I most adored—and best understood—the single frame images of Sergio Aragonés’ “The Shadow Knows.” In these features, adults and children were outwardly composed—but behind them, in shadow, was another story of rage, lust, fear, greed. The adults smiling through a boy’s concert were, in shadow, smashing the kid’s violin on his head. The couple politely chatting on a sidewalk were, in shadow, passionately kissing. Seemingly upstanding adults, in shadow, gathered around kids’ TV shows or ogled nude sculptures or kicked people into wishing wells.

The tension between public actions and private desires, encapsulated briefly, in images? Sounds like the makings of a great short story. Or maybe a few famous poems.

Inside those books was an imaginative space where I had power. There, my fears were no more shameful than a man scared of the high dive. There, I could be wrong about everything—who Timothy Leary was, why Madison Avenue was such a big deal—and it never really mattered. I could be brave and snippy and snarky and gross. I could “plunder [the books] for clues to the universe,” as Roger Ebert once said—and sometimes glimpse “the machine inside the skin.”

Now, as I type, my desk is stacked with the few remaining books from my collection. My daughter walks in. She asks:

Question: “What are those books on your desk, Mama?”

Answer 1: “Do I hear your father calling you?”

Answer 2: “Shhh! Mama is doing research.”

Answer 3: “Oh, child, these trashy books? These are your inheritance.”