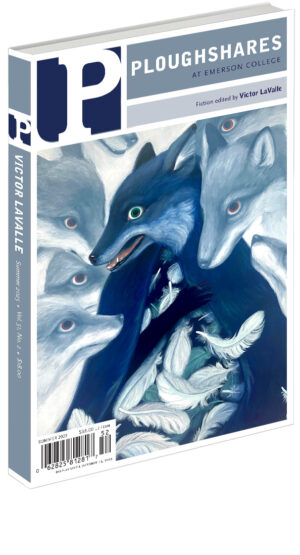

The Horror

Issue #164

Summer 2025

1. She angled the camera for what she called the money shot: two attic eyebrow windows and a nose-shaped balcony off the second-floor master. If we squinted from the driveway, we could make out the mouth, the Dutch breakfast door that cut...

Purchase an archive subscription to see the rest of this article.

Purchase an archive subscription to see the rest of this article.