The Ploughshares Round-Down: The State of Poetry in the US

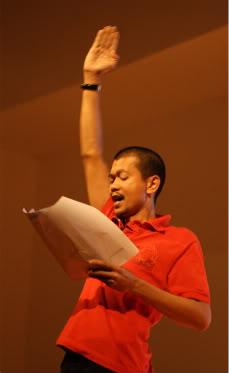

Early last month, PEN International publicly condemned the killing of Thai poet Mainueng K. Kunthee. The poet had been shot to death on April 23rd, presumably because of his public criticisms of the monarchy and Thailand’s lèse majesté law. Known as a poet of the people, Kunthee was immensely popular; his work “spoke of social justice, the rights of the poor, and in protest of laws against free expression.”

After Kunthee’s death, free expression became even more suppressed in Thailand–thus the PEN condemnation six weeks later. “PEN International is deeply concerned for the safety of writers, academics and activists in Thailand,” the report states, “who are increasingly at risk of attack and imprisonment solely for the peaceful expression of their opinions…”

PEN’s report and condemnation recirculated the story on June 10th, with write-ups in LA Times and The Poetry Foundation, among others. As it happens, three days later, the New York Times published a piece entitled “Poetry: Who Needs It?”–in which the author summarizes and laments the overarching neglect–if not general loathing–of poetry today.

Confession: I lost a lot of time on the crazy proximity of these write-ups. I mean, the “What’s become of poetry?!” question is nothing new in America; it’s basically a meme by now. But authors who bemoan, defend, and/or wax nostalgic about poetry’s altered role in society are largely silent about the many places in the world where poetry is terrifyingly robust. The juxtaposition of “Who Needs It?” with the extreme danger faced by beloved poets like Kunthee begs the question of how and when poetry in the U.S. became safe, minor, niche, ineffective, nonpolitical, anti-political, pretty, petty, occasional. And largely relegated to classrooms.

Poet Adrienne Rich often noted that the United States is the only country in the world where political poetry is regarded as taboo. (Some would add Britain.) “Go to Latin America,” Rich said in an interview with the Boston Review, “to the Middle East, to Asia, to Africa, to Europe, and you find the political poet and a poetry that addresses public affairs and public discourse, conflict, oppression, and resistance. That poetry is seen as normal. And it is honored.”

Rich also mentioned that such poetry can be dangerous–and of course it is–in places where it regularly resists powerful forces and actively connects with the public. So if poetry doesn’t matter in the U.S.–if our seasonal major-media laments are valid–it’s perhaps in part because:

1. For decades, poetry in the States largely avoided (or scorned) politics, in part to “bolster a surveillance-mad Cold War regime.” Literary scholar Brian Reed notes that after WWII, poets determined

that technique, structure, diction, tone, and other formal aspects of a poem are crucial in assigning its value, whereas its overt political and ethical commitments are of secondary importance.

There are of course exceptions, but political poetry since the ’50s has often questioned power via heavily-theorized uses of language or form that readers cannot engage in without prior interest and/or the privilege of education. (Thinking oneself political while knowingly alienating “the masses” is a special kind of fail.)

2. Freedom of expression may be ho-hum here? Not that we don’t value our rights, but we’re certainly accustomed to hearing socio-political opposition in the States. Dissent doesn’t (often) strike us as crazy or dangerous, and it’s not breaking the law. So–meh?

Still, one can’t attribute poetry’s popularity in other places strictly to a lack of “free speech.” After all, poetry–particularly when it’s as direct as Kunthee’s–doesn’t typically hide its dissent behind Mysterious Poetry-ness. So perhaps the difference in America isn’t our freedom, but our failure to put poetry’s nuance, complexity, imaginative linguistic parallels, and general memorability to public use for messaging, social enlivening, or community-building. Or maybe it’s too safe and sanitary?

3. The assumption that poetry doesn’t and won’t ever matter to the masses makes a lot of poets discount–or even vilify!–hardcore attempts to connect poetry with a wide public. Poetry has long assumed people will come looking for it. When they don’t, it gets nervous and/or nostalgic–inciting laments like this one . . . as if there’s nothing to be done. But let’s be honest: often, to encounter poetry in the States, a reader must either be in an English classroom or have prior/given interest–she must be purposeful about seeking poems out. (After all, poetry goes looking for no one.)

But here’s the thing: If a reader doesn’t seek poems out, that’s not her fault–any more than it’s your fault you didn’t hear Pharrell’s “Happy” before the moment you did. You can’t (or at least, won’t) go looking for something you don’t know exists, something you don’t even know you want. “Happy” found you. It was made for public circulation. (Ok, it’s not the best analogy, but go with me).

Similarly, activistic, challenging, rebellious, politically-relevant, heretical, publicly vital, innovative, outlandish, investigative poetry will work to get out and get itself heard wherever and however, because that’s the point. The public is the point: public movement, involvement, opinion, access, even health. In many parts of the world, poetry addresses oppression, conflict, and trauma–in an audaciously accessible way that meets and moves the masses.

In closing:

To his credit, the author of the “Poetry: Who Needs It?” doesn’t get crazy-mopey about poetry. But like similar write-ups, his depiction of poetry as increasingly marginal is blind to all the places in the world where this is profoundly not the case–where poetry fuels (and/or represents) entire social and political movements, thereby endangering both its writers and readers.

The fact that poetry is so obviously (and terrifyingly) relevant in other parts of the world should tell us that if poetry has a strange, small following in America, it’s not necessarily because “Welp, who needs it.“ A great deal of American poetry has (rather actively) detached itself from the public, making itself an elite expressive form that’s been tellingly compared to ballet and opera. If “the masses” aren’t scrambling to get to that party, I’m not sure I can blame them.

Perhaps no one should be grieved or surprised that the crowds that come panting after poems are as small as we’ve made the work itself.