Retelling Tales: A Writer’s Guide

So much of modern cinema and fiction revolves around the anti-hero and the sympathetic villain. Our culture seems to need our protagonists to be damaged or troubled in some way. It’s as if in some grand pursuit of Nietzsche’s rejection of absolutes, we can only accept shades of gray. Those moral shades of gray are particularly represented when authors elect to take villainous or marginalized characters and bring them to the forefront by writing their stories. While childhood stories clearly draw the line between good and bad, it becomes murkier as we age. Be it experience or expectations, we want more than the Big Bad Wolf or the Mustache Twirling Fiend. Telling a baddie’s story is one way to achieve that complexity.

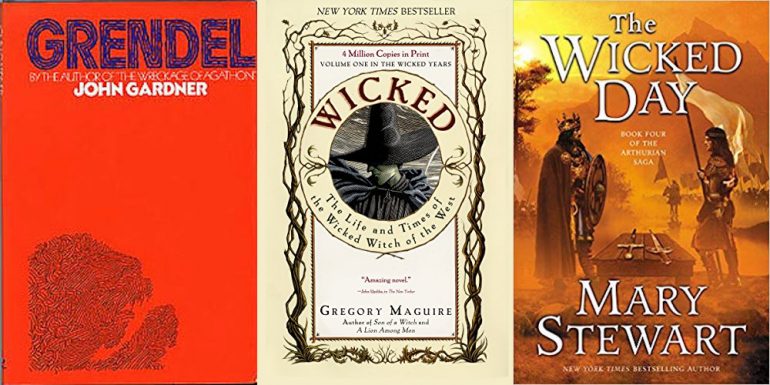

Many literary villains, from the Wicked Witch to Cinderella’s stepsisters, have been given their own tales. I’ve even given it a pass myself–my master’s thesis was a twist on the Arthurian legend looking at Mordred’s developmental years. The appeal of putting villains or even marginalized characters in the driving role of the narrative allows both the writer and the reader to explore a familiar story in a fresh way. Success in such ventures is mixed: for every Grendel, there is a Lo’s Diary. Even more arduous is crafting your work so that it has literary merit and is not just some well-written piece of fan fiction. Some things to consider:

Research

When electing to play with existing source material, research is essential in the early stages of project development. Understanding what has come before is certainly important with any work, but it is indispensable when constructing a character from existing stories. Even if you don’t read all of the works, a survey of them, perhaps with details in your notes, will help avoid the snafu of rehashing something that has already been done.

I spent a good six months leading up to the actual writing of my thesis reading various Arthurian texts. As my focus was on Mordred, I read poems, plays, and novels, taking extensive notes on various character descriptions, dialogue, and characterization. I studied art works depicting him. He became a bit of my obsession. In the end, I not only had an understanding of what had already been written, I had begun to understand who my Mordred would be and how he would differ from Mary Stewart’s Mordred or Thomas Malory’s Mordred.

Motive

As with any story, it is important to consider why the story you want to attack needs to be told. In the case of retelling from the villain’s, or even a minor character’s point of view, this consideration becomes more crucial. Often times these stories are beloved, ripe with sacred cows. When constructing Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West, his take on the villain from L. Frank Baum’s Oz series, Gregory Maguire elected to tackle this world for an adult reader, as opposed to the child audience of the original series and popular film. It was a wise decision in that grownups who had come of age familiar with the story could still contextualize the story while enjoying a dirtier vision of Oz. Maguire had a clear motive and purpose in his approach.

For my own work, I was inspired by the idea that the Arthur legend seems to continually reinvent itself–the 1950s brought T.H. White’s Once and Future King featuring Mordred the anarchist; the 1980s, Marion Zimmer Bradley’s feminist The Mists of Avalon; and so forth. Based on my coursework and my lifelong infatuation with Arthurian Literature, I felt I had something to say about Mordred that had not yet been addressed.

Multiple Inspirations

It isn’t enough just to take the source material and flip it on its head; you must bring something more to the table. Jean Rhys took the marginalized villain of Jane Eyre and transformed Bertha into oppressed Antoinette, the heroine of Wide Sargasso Sea, using her as a vessel for the discussion of postcolonial issues in the Caribbean. With Grendel, Gardner moved beyond the source material. As much inspiration is drawn from Sartre and nihilism as from the Anglo-Saxon poem. Building on the idea of purpose, pulling in additional inspirations helps make the work uniquely your own.

In the case of writing a creative thesis, one of my goals was to encompass as much of my graduate coursework as possible. Thus my influences included transcendentalism, Western writing (specifically Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian or The Evening Redness in the West), Anglo Saxon linguistics, and many themes of postcolonialism. By infusing my own background into the work, it allowed it to develop its own identity.

Choices

One question that you must address for yourself is how faithful you wish to be to the source material. When writing a prequel, like Wide Sargasso Sea, it becomes less relevant. Charlotte Bronte gave so few details about Bertha that Jean Rhys was left to invent much of her main character’s life. Only in the book’s final chapters does it intersect with Jane Eyre. The disturbingly terrible Lo’s Diary by Pia Pera changes so much of Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita that it seems questionable if the author actually read her source material.

Arthurian Literature is an easier starting place in part due to its own transformative nature. How an individual defines his/her vision of that world depends entirely on a personal frame of reference, be it Geoffrey of Monmouth or The Sword in the Stone. When dealing with something like Oz or Jane Eyre or Beowulf, it is much more difficult to make changes without alienating readers. The key, I believe, is to make sure whatever changes to the narrative are made with purpose and evolve organically from the story you are telling. Changing an ending or a character just to change it is unfair to the reader and the source material. Even working with another’s source material, however, allow the work to become its own entity.

Whether penning the true story behind a literary monster or plucking a character from the background to spin the story fresh, retelling familiar tales can be a challenging, yet rewarding experience for the writer and the reader.