Triangular Relationships

In a previous blog post, I mentioned my difficulty with conflict and tension. For this reason, I love triangular relationships, which bring up conflicting desires, competing loyalties, and dilemmas. All the things that make a juicy story go. When I was just starting out writing fiction, when my writing tended to be a formless blob and I learned that good writing needs a shape, a design, I turned to the idea of things happening in threes, and then I turned to triangles. As I learned along the way, there are many, many ways you might use triangles in your fiction.

Take for instance, Mavis Gallant’s nine page story “Lena,” set in Paris. In this story, Edouard visits his eighty-year-old first wife, Magdalena, in the hospital. She had, for years, refused his request for a divorce. By the time he could legally remarry on the grounds of separation, his second wife, Juliet, was no longer able to have children. And by the time of the present action of the story, she had died. Edouard is obliged to help Magdalena find a spot in the hospital, and she demands he bring her “home”—he is the closest thing to family she has.

Intertwined in this triangle of personal relationships you have the religious conflict—Lena had converted from Judaism to Catholicism and holds very strongly to the notion that Edouard is her husband—and political tension. Juliet, Edouard, and Juliet’s parents are all involved somehow with the French resistance during World War II, while Magdalena stays behind in Paris. When Edouard recalls the lunch in 1954 he had with the two of them, when he was supposed to ask for a divorce but failed, he associates Magdalena’s perfume, jasmine or gardenia, with the profiteering side of war.

There’s a lot there in nine pages. I could go on. But I’ll bring up another example.

A roiling triangular relationship is at the root of Gunter Grass’s World War II novel The Tin Drum. Agnes Matzerath, the mother of Oskar, the protagonist, is in love triangle between her German husband Matzerath and her Polish cousin Bronski. Again, the political and religious issues are intertwined in this love triangle that goes on for years and years. Agnes is deeply ridden with guilt; perhaps she stays with her husband because she’s Catholic or perhaps she stays with him because he’s German and she was given advice to bet on the Germans, not the Poles. The narrator describes the three of them in terms of war and refers to the three of them as a triumvirate. Agnes constantly moves between weekly visits to Bronki in a rented roomand weekly visits to the confessional; later, as her guilt and self-destruction ratchet up, she begins compulsively eating fish, and then eels, and compulsively vomiting. Each character feels immense guilt and it spills over to Oskar, who may be Bronski’s child and who, later in the novel, says he was the cause of his mother’s death–with his incessant drumming and high-pitched screaming and glass breaking.

In another vein, Peter Mountford’s novel The Dismal Science highlights not a love triangle but a familial triangle. It is, in part, about the effect on a family of three of losing one crucial person: the wife/mother. Mountford writes:

“In the case of Cristina’s death, there were at least a dozen serious subsidiary losses for Vincenzo. Enormous plans that needed to be unwound, countless relationships that unraveled. The worst of all had to be the damage to his relationship with Leonora, who had been closer to her mother to begin with. Still, the family had been triangular, the sturdiest shape known, and when one of the points was wiped out, the remaining two formed a line, which stretched in search of some new formal identity.”

All kinds of triangular relationships are all over literature with good reason. They bring out the emotional complexity of characters’ lives and are enormously useful in highlighting both their internal and external conflicts.

The Prompts

1. What triangular relationships, competing loyalties, and internal conflicts have you observed or experienced directly in your life? What is at stake with each of those competing loyalties? How does that affect the behavior of those people in the triangle? Make a list of them and think about how you might plumb them for conflict. Take this core emotional work and transform it into something powerful.

2. What are you working on right now that has three important characters? Are there superfluous characters that might be cut? For example, in the first novel I wrote, I started out with a mother, father, and two daughters. But one daughter was a weak character contributing very little. So I merged them, and from that, the loss of the father became a powerful force for the mother-daughter conflict to more fully erupt.

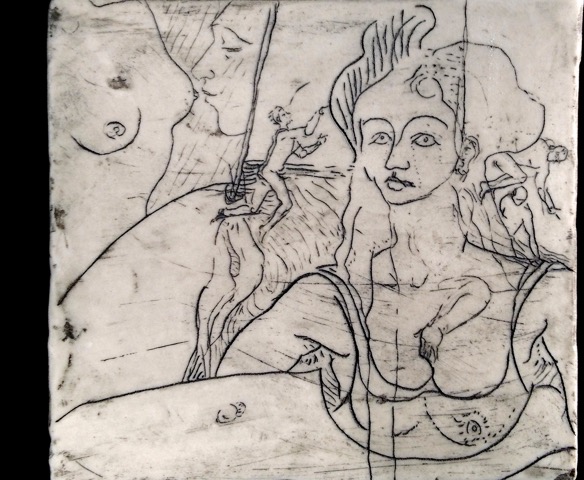

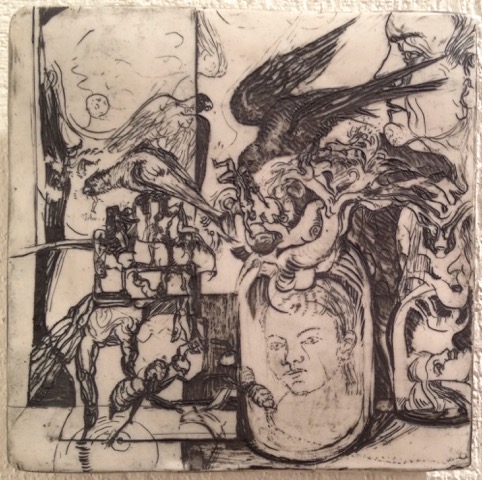

3. Finally, you might look to Kathleen Skeel’s wonderfully suggestive drawings (above) to generate new work around this idea of triangles.

Once you’ve mastered the triangle, you might try other shapes, as suggested by Jez Burrows’s “Geometic Relationships More Realistic Than the Love Triangle”.