Editor’s Note

We’ve lost many bright lights in recent years–writers whose work shaped literary spaces, friends, students, and readers on and off the page. Among them are three writers whose work appears in this issue: Jennifer Martelli, Michael Burkard, and Elizabeth Bernays. These writers remind us of language’s power to confront despair, challenge apathy, and craft beauty from fracture; to reach outwards beyond the personal, beyond the page, toward shared experience.

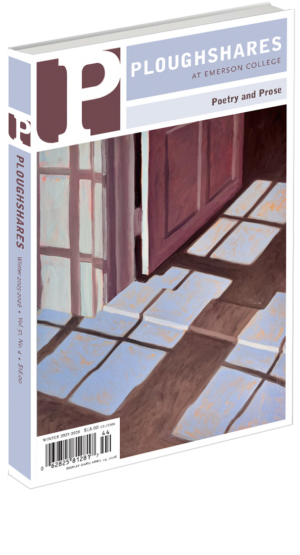

The window in Mary Royall’s “Threshold,” the cover art for this issue, captures what Martelli, Burkard, Bernays, and so many other writers published in these pages do so beautifully: refracting the outside world inward, transforming, projecting, turning landscape to language. In her poem “Someone Else,” Maggie Dietz writes, “I entered someone else’s suffering and when I / Surfaced I looked behind me into the sheen of it.” Here, Dietz enacts not only the recognition of another’s suffering, but the deeper act of engaging with it, entering it, seeing it again—the action we take when we spend time with and share the poems we love.

Jane Goodall, another great humanist who recently passed, once argued that “real hope requires action and engagement.” Goodall saw hope as a misunderstood emotion and, considering it as a survival skill rather than empty idealism, spread awareness about interspecies relationships and climate change through her enormously important (and enormously hopeful) work. These days, due to prevalent hate, loss, and challenges to personal freedoms and expressions, action and engagement feel less and less possible. Maybe, though, taking action can include the act of sitting still, as Goodall sat with nature, or in our case, as readers, as we sit with the work of great writers.

Goodall also said that “the greatest danger to our future is apathy.” The opposite of apathy is empathy—and what is empathy but translation? A rendering of someone else’s experience, rewritten by a particular brain. Transformation, new light. This nearly impossible work, which is also the work of poetry, is explored so deftly in Mostafa Ibrahim’s poem, “So-and-So,” translated from the Arabic by Abdelrahman ElGendy. The opening lines read, “So-and-so brushed / my shoulder as gunshots / cracked. // So-and-so: I never learned / his name, so I called him / cousin, and that was / enough.” The action of hope, I think, asks us to engage in a dialogue with what’s living and what’s lost. It is a moment of recognition that transcends knowing, speaks into what is vanishing.

Jennifer Martelli embodies this reach, this hope-as-action, in “Gigan Transforming Sadness.” In the poem, a figure stops short from drowning himself in the river: “Digging into dirt saved his life,” Martelli writes, “leached sadness from even the tips of his fingers.” While the figure in Martelli’s poem stays rooted to earth and thus the living, Michael Burkard’s speaker in “Ghost” seems to transmigrate, to speak from the beyond: “I was not Michael— / I knew because the rain / chose to fall near / but not upon me, / and it wasn’t to make / an exception.” And Liz Bernays, in her essay, “West Shed,” transforms this tension between inner and outer worlds in her reflections on art-making and solitude: “Writing, I found something new that was yet nameless. It was related to peace. It had to do with solace.”

The work in this issue, as I return to it again and again, reminds me of the purpose behind the difficult work of writing, and the impossible but necessary work of translation. This winter, may this powerful collection of voices bring you new light, solace, and hope.