“Cow Country” And The Problem With Pseudonyms

A recent post on the Harper’s blog has gotten me thinking about pseudonyms. In it, Art Winslow posits that a new novel, Cow Country, from an obscure vanity press was actually authored by Thomas Pynchon under the pseudonym Adrian Jones Pearson.

As evidence, Winslow points to certain aesthetic similarities between the author and Pynchon, including its meta quality and the use of outlandish names like “Dimwiddle.”

Cow Country is at heart a playful novel, side-splittingly funny in a goofy, almost junior-high way, overworking its material far past expected bounds, taking Emily Dickinson’s idea of telling it “slant” and running with it in wild abandon, sometimes to the extent of losing its very breath. There will be recurrent talk of lost civilizations, forgotten cultures, and tongues. The novel seems to revel in its own delight of cultural esoterica, and it displays both a fondness for and a corresponding suspicion of countercultural motifs of the 1960s–70s as well.

Sure, sounds like Pynchon. Also Pynchonesque is the premise of the imagined scheme: to expose the advantage granted to “names” over unknown authors while a book’s content goes ignored.

Winslow’s piece is fascinating, well-reasoned, and worth a read. Unfortunately for lovers of a good conspiracy theory, both Pynchon’s publisher and his agent Melanie Jackson, who is also his wife, denied the theory to the Times. Said Jackson in an email, “He did not write Cow Country.” Well, that settles that.

It’s unusual in this day and age for writers to eschew attention in favor of working anonymously (for more on authorial anonymity see our recent Round-Down). For one thing, those favorites and retweets feel so good to a fragile ego. For another, where satire is concerned, opprobrium of the government or ruling class no longer results in punishment.

But this wasn’t always the case. Early practitioners of satire routinely used pen names to avoid running afoul of the authorities. Jonathan Swift originally wrote as Lemuel Gulliver, M.B. Drapier, and least convincing but my personal favorite, Isaac Bickerstaff.

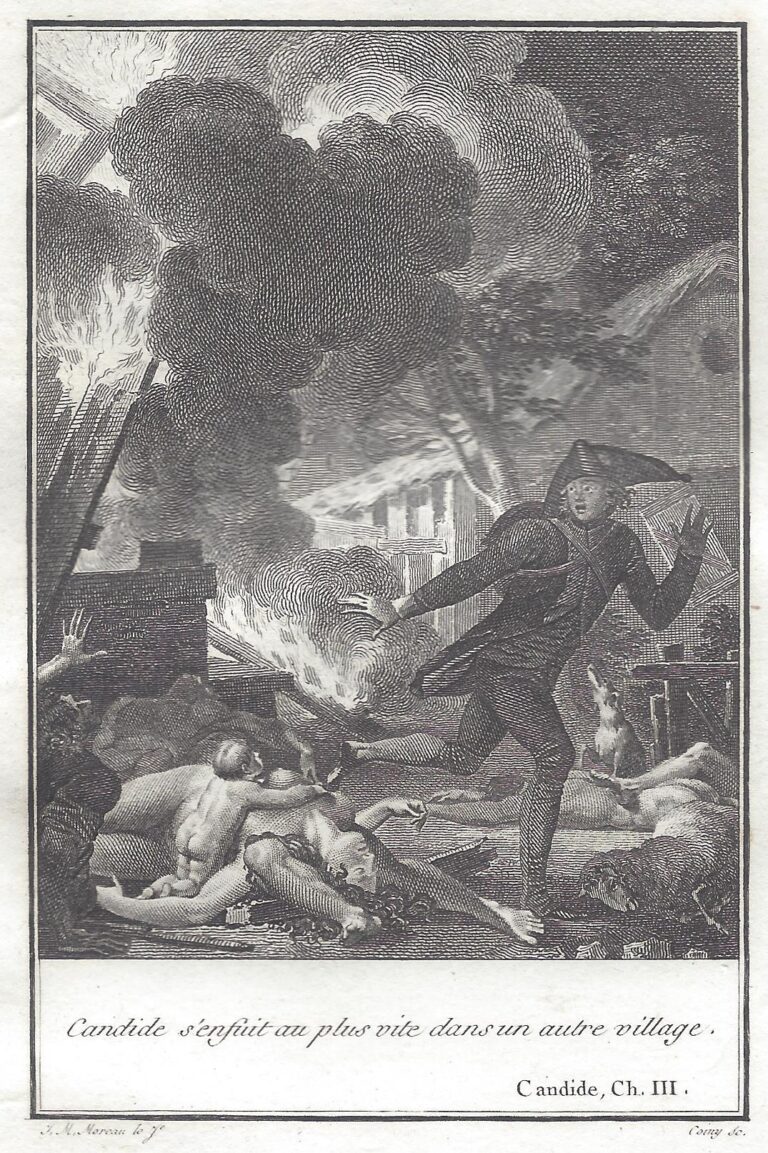

Likewise, Moliere and Voltaire are both pseudonyms. The former was an actor before becoming the master of French comedy, and Moliere was his stage name. The latter adopted his pen name to mark a break from his noble family.

Mark Twain, of course, was the pseudonym and avuncular public persona of Samuel Clemens, used to keep Twain, the larger-than-life bon vivant, distinct from Clemens, the real man. In Life on the Mississippi, Twain explains that the name was co-opted from a riverboat captain who used to contribute to a local newspaper. As with every Twain anecdote there’s a good chance that the tale is a fabrication:

The old gentleman was not of literary turn or capacity, but he used to jot down brief paragraphs of plain practical information about the river, and sign them “MARK TWAIN,” and give them to the “New Orleans Picayune.” They related to the stage and condition of the river, and were accurate and valuable; and thus far, they contained no poison.

Do pseudonyms have a place in contemporary comic literature, or are they a relic of the past? In a perfect world, all books would stand on their own merits, and the authors’ names would do nothing but determine where they are shelved in the library.

To return to Cow Country, the shadowy Adrian Jones Pearson claims to have written other novels under different pseudonyms, with the goal of manufacturing a “disposable authorial personae for every book.” Winslow suggests that this is an honorable approach, but in an age where fake identities are no longer really needed to protect the satirist, it’s hard not to see it as, at best, a gimmick and at worst a kind of attention-seeking con. After all, Pynchon has denied being Pearson, but Pearson has yet to deny being Pynchon.