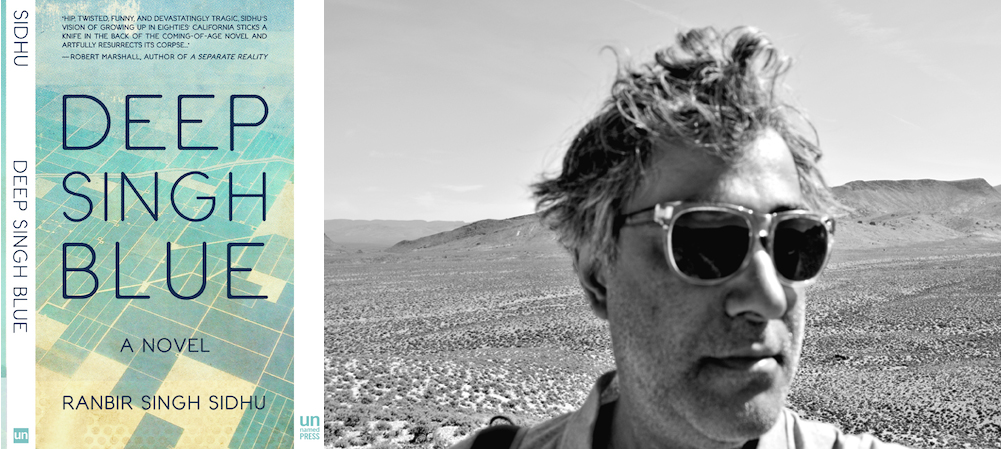

Look Deep: An Interview with Ranbir Singh Sidhu

Ranbir Singh Sidhu writes stories, essays and plays, takes photographs, and dreams of making movies. He was born in London and grew up in California. His first novel is Deep Singh Blue (Unnamed Press), which the novelist Alex Shakar calls “a work of ferocious bravery, intelligence, and art.” He is the author of the story collection Good Indian Girls (Soft Skull) and is a winner of a Pushcart Prize and a New York Foundation for the Arts Fellowship. His stories appear in Conjunctions, Alaska Quarterly Review, The Georgia Review, The Missouri Review, and many other journals.

Titi Nguyen: How did this book come about?

Ranbir Singh Sidhu: I was working in Sri Lanka staying with a friend when we discovered the maid had been using the house secretly as a brothel when we were away—and not only that, but she was also using it as a love nest for a very serious Sri Lankan VIP. Things got a lot stranger very quickly, with death threats and all sorts of threats flying around—and as my friend was out of the country at the time I found myself in the firing line of a lot of screaming.

In the middle of all this, to distract myself, I wrote a comic story about a Sikh kid who announces one night at dinner that he’s decided to become a Jew. I drew on my own family for the dynamic—it was the first time I’d ever done anything like that and I enjoyed the sense of liberation it offered, to take people I knew, a world I knew, and transform it yet keep the heart of who those people were. I’d always been suspicious about autobiographical fiction, but this one foray offered a conversation with my childhood that I’d never had before. The story never went anywhere, but the character of Deep was born then, and it was out of getting to know him that the novel emerged.

TN: What really struck me about this story is how love and hate are so deeply intertwined. Can you speak more to this dichotomy?

RSS: This novel is very much a love story, but of necessity a complex one. But more than that, it’s a love letter to the supreme fucked-upness of modern Punjabi families, at least the ones I’ve known and grown up around, both in the US and the UK. For a character like Deep, who grows up in that world and never feels any kind of firm ground under his feet, the line between love and hate is very permeable. I was also interested in the ways that racism buries itself in people who are subjected to it from a young age, how it can become a second skin. In this case, Lily uses it as a defense against her own demons, and for Deep this is a kind of power that he finds incredibly attractive, a way to transform something that up to then he had viewed purely as an attack.

TN: We get a profound sense of disconnect within Deep’s family expressed through silence, lies, denial, and menace. Can you tell me more about this?

RSS: Most families are built around lies, but I suspect that in Indian families, especially the north Indian Punjabi families I write about here, it’s at the very heart of who they are. This is not meant as an indictment, just an observation, and it’s something I’ve been interested in all my adult life. It’s hard to explain to an outsider how central both denial and the lie are in such families, how pervasive they are, and as a result how relationships become deeply warped. Silence—both literal and metaphoric—was at the center of my own upbringing, and I’m glad that I’ve found a voice in this novel that is able to communicate something of what that world was like and still is, I’m sure, for many people.

TN: One of the things I find so poignant in your novel is the notion of country and home, a personal preoccupation of mine. Deep has dreams of discovering his own country, Uncle Gur is obsessed with Sikhs breaking out on their own land. How does this idea of dislocation and yearning for refuge figure into your work?

RSS: It’s personal for me too. These days I don’t even have a home, I just sort of wander, which is not always the easiest way to live a life. I told myself I was looking for a place I could call home, but I no longer think that’s ever going to happen. Then the question becomes whether I find a place where I think I can actually stand to live for an extended period. That’s not New York, and I don’t know where it is right now. All of that sense of dislocation fed into the novel, and into Deep’s character and his longing to build a phantom country.

TN: That’s interesting in light of the fact that you’ve been living on an island in Greece for at least a year, so the precarious nature of life must also be in the air due to the debt and migrant situations.

RSS: Exactly, and I found myself very much identifying with the refugees—my Mom was a refugee—and also with Greeks in general against what often felt like an utterly uncomprehending and sanctimonious EU. I wrote the final draft of the book while living there, and I’m sure some of the strangeness of life in Greece today has seeped into these pages.

TN: Your relationship with your publisher seems to have come at that time too. So on the subject of homes, what was the process like of finding one for this book? From your view, what does the publishing scene look like right now for minority writers in the Western world?

RSS: It sucks out there—I mean it sucks in general for writers, but if you’re not white, then you’re crushed into about as small a box as you can imagine. The expectations of what someone with a name like Ranbir Singh Sidhu both can and should be writing are so narrow as to be laughable. That said, I’ve been very lucky with my US publisher, Unnamed Press, but it took a long time to find them. I think the publishing industry should be embarrassed. I mean, television is doing more interesting work around South Asians—I’m thinking Aziz Ansari and Mindy Kaling—than the all-too-often deathly dull stories about the delicate lives of upper middle class Desis that you find being peddled as literature by the big publishers these days. Television! I know that sounds harsh, and of course, there’s good writing out there, some really fine writing, but what I want to push forcefully against is the construction of what is essentially a monocultural image of the lives of South Asians in literature, which I know for a fact is grossly false.

TN: What are you working on these days?

RSS: I’ve just finished a very long book—the one I was working on when all that craziness in Sri Lanka happened and I needed a distraction. It’s called The Echoes, and is about the end of the world, which both happens and doesn’t happen in 1991. At its heart, it’s about memory and its erasure, and also its transformation. It’s also got a lot of ghosts and other realities, a former rodeo clown, a serious Camaro enthusiast, and lots of people who are not really people at all.