Love and Pain: An Interview With Diane Schoemperlen

One could argue that the work of Kingston, Ontario writer Diane Schoemperlen is highly unusual even beyond its incredible strength: a more lyric prose managing publication through larger and more mainstream Canadian publishers. Given her work, I was curious to engage with her memoir, This Is Not My Life: A Memoir of Love, Prison, and Other Complications, in which she takes a close and candid look at her relationship with a federal inmate serving a life sentence for second-degree murder.

Born and raised in Thunder Bay, Ontario, Diane Schoemperlen is the award-winning author of twelve previous books of fiction and non-fiction. Her works include several collections of short fiction, most recently By the Book: Stories and Pictures; three novels, In the Language of Love, Our Lady of the Lost and Found, and At A Loss For Words; and the non-fiction book, Names of the Dead: An Elegy for the Victims of September 11.

Her early collection of stories, The Man of My Dreams, was shortlisted for both the Governor-General’s Award and the Trillium Prize. Her collection of illustrated stories, Forms of Devotion: Stories and Pictures won the 1998 Governor-General’s Award for English Fiction. It was recently published in Quebec by Éditions Alto, as Encylopédie du monde visible.

Her work has also been published internationally in the United States, Britain, France, Germany, Spain, Sweden, Korea, and China. She received the 2007 Marian Engel Award from the Writers’ Trust of Canada. She has been Writer-in-Residence at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario, and St. Mary’s University in Halifax, Nova Scotia. She has lived in Kingston, Ontario, since 1986.

Q: The prose of your memoir, This Is Not My Life: A Memoir of Love, Prison, and Other Complications, feels a bit different than the prose of your fiction; your sentences feels straighter, as though you are more conscious of articulating the particular details of the story. Was there a difference, in your mind, in the prose of your memoir over that of your fiction?

A: The short answer to this question is yes, most definitely yes. The prose of my memoir is intentionally different than the prose of my fiction.

Here’s the long answer. It took me about three years to write this book. The first year was spent figuring out what I wanted to say and how I wanted to say it. One of the main issues was figuring out the voice and the tone. I found that the usual more “literary” and embellished style of my fiction was not serving this story well. So I had to put all that aside and find a new voice for myself. Once I stopped trying to make this book fit into what I thought I knew about writing a book, it all began to come along more quickly. I decided I had to do the opposite of what Emily Dickinson advised: I could not tell it slant, I had to tell it straight. I think of the prose in my memoir as a kind of “plainsong”…it’s just me, sitting at the kitchen table, telling the reader what happened. Because this book is nonfiction, I knew it was very important to get the facts and all the details straight. I also knew that I had to be as honest and open as possible, without trying to hide behind any kind of literary jazzing around.

Q: I find it interesting that you saw the emotional honesty required for such a project also required a straighter narrative. I would suspect that there might be other writers, such as Susan Howe (specifically, from That This) or some of the writers in the anthology The Heart Does Break: Canadian Writers on Grief and Mourning (Penguin, 2009), edited by George Bowering and Jean Baird, that would disagree with you on your argument for a straighter narrative line. Was this a difficult shift to make? And what do you think was gained (or even lost) as a result?

A: During that first year of figuring out how to write this book, I read a great many other memoirs and also several books about how to write memoir. Sometimes this was helpful but sometimes it was confusing. Eventually, I came to the conclusion that there are as many different ways to write a memoir as there are to write a novel. This had never bothered me when writing fiction and so I decided it shouldn’t bother me when writing memoir either. In both genres, it is always about finding the form and the voice that best suits the story you are trying to tell. Some of the memoirs I read and most admired were indeed more literary or experimental in form but, try as I might to make it work, that was not the right approach for me for this book. In fact, for the years I was working on the book, the subtitle was different than it is now. It was “The Story of My Prison Years.” In fact, the idea of “story” is thematically important throughout and sidestepping the actual word “memoir” while I was writing helped me to tell the story the way I wanted to. Yes, it was a difficult shift for me to make but once I made it, I knew I was on the right track.

One of the reasons I decided to write this book as a memoir (rather than turning the whole experience into a novel) was because I wanted to write about more than the relationship itself. I wanted to “educate” readers as to how the Canadian prison system actually works. When I first became involved with Shane, I realized that, like most people, what I thought I knew about prison was largely based on American movies and TV. The Canadian system is quite different. I also had a lot to say about the Harper government’s “Tough on Crime” agenda and this political aspect of the book needed to be integrated into the narrative and explained carefully.

Now that the book is completed and out there in the world, I feel I managed to combine these various aspects in a readable and compelling manner that would not have worked as well in any other form or voice.

Q: A number of your works of fiction have emerged from very specific structures set in place before the writing began, whether the one hundred words that prompted the one hundred chapters of In the Language of Love, or each story in Forms of Devotion illustrated with collages. I’m curious as to This Is Not My Life, and whether or not you’d already a particular structure in mind when you began. Upon first entering the book, it would seem as though there isn’t an overt structure in place; were there difficulties in pushing the writing ahead without utilizing a pre-considered structure, or was it simply not required?

A: So many things about writing This Is Not My Life were different than writing fiction had been for me and this matter of structure both was and wasn’t one of them.

I wish I could remember who said that when you’re writing fiction it is like starting with a blank canvas and you must fill it up. But when you’re writing a memoir that canvas is already too full and you must take things out while also shaping the story into a narrative form. I had no idea how to do this! So I began by doing something I’d never done before. I wrote what I called the “skeleton” which was a kind of detailed chronological outline of everything that had happened during and immediately after my relationship with Shane. It ended up being over 100 pages long. Although I didn’t keep a journal while we were together, I do keep track of many things on my calendar (yes, an old-fashioned calendar that hangs on the kitchen wall above the telephone) and in my Day-Timer. As I mentioned in the book, being in prison generates an awful lot of paperwork so I also had that to work from in reconstructing what had happened when. I wrote this skeleton in the third person, using my middle name “Mavis,” to help myself detach from some of the more difficult events that occurred.

This skeleton naturally fell into five parts, each of which ended with a parole hearing. In the prison world, the parole hearings are the deciding events that determine what is going to happen next: if the inmate will remain where he is or if he will move forward to the next step. The parole hearings thus necessarily determined the stages of our relationship.

So then I had the structure: five chronological parts to be followed by an epilogue.

But one of the things that was emphasized in all the books about how to write memoir was that it should not be told chronologically. I struggled with this but, because of the nature of the story of our relationship, I did not see how I could write it otherwise. How could I have him shopping with me at Loblaws on one page, sitting in prison on the next, living at the halfway house in Peterborough on the next, and so on? I was sure this would all be just too confusing for the reader. In my fiction I had never had any trouble dispensing with the “rules” that might come into play when writing a novel or a short story. So now I had to dispense with this “rule” too and work within this structure which best reflected and honoured the story as it had developed.

Interestingly enough, once I had finally settled on using the chronological structure, the figuring-it-out year was over and the actual writing began. Just as usually happened with my fiction, once I had the structure clear in my mind, I could move forward and tell the story. It was the structure that propelled the narrative. I did not then actually begin at the beginning and write through to the end. I wrote the easier parts first, as a way, I suppose, of working up to the hard parts. But because I had the structure, I knew where everything belonged and how one thing led to another.

Q: What is it about constructing a pre-established structure that appeals? One could compare it to putting flesh upon the bones for the sake of a final shape. As much as constructing such a shape early in the process of a manuscript might fuel the writing, do you ever worry about the limitations that such pre-considerations might have? Do you ever feel trapped?

A: Of course every writer has a different process. For me, having a pre-established structure allows me to see the shape of the whole book in my mind and that provides a sense of security and direction. Rather than feeling limited by the structure, I find it liberating. When I run into places where making what I want to say fit into the structure is tricky, I very much enjoy the process of puzzling out how to make it work. I feel a kinship with the Oulipo group who deliberately worked within constraints to facilitate their creative ideas. I don’t mind feeling temporarily trapped! However, if that feeling became too persistent, I would have to admit that the structure wasn’t working and find another structure instead. This hasn’t happened so far…but it might someday.

Q: Now that you’ve a bit of distance from the book, how well do you feel you accomplished what you’d set out to do? And I’m always curious about this type of memoir: has writing out that story and releasing it into the world allowed you any kind of closure? Have you been able to learn from the experience and move forward?

A: I don’t suppose any writer is 100% happy with the final product but in this case it’s close! Writing the book was so difficult and now when I hold it in my hands, I do feel very proud of it. And yes, writing out the story and releasing it into the world has given me a deep sense of peace. I will carefully avoid the word “closure” here because it’s a word that has always bothered me. Being a literal-minded person, to me that word means something that is over and done with and locked away forever (pun intended). While the relationship itself is over and done with, that experience is now part of who I am and it will always be there within me on so many levels. I have no regrets about the relationship and working it through in writing the book was more therapeutic than I had expected. I feel I have emerged from all of it as a better and stronger person. Rather than closing off that part of my life, in fact writing the book and sending it out into the world has broken me wide open in a wonderful way I could never have imagined ahead of time. There were times when I felt very vulnerable about this book because I had revealed myself so openly. And I knew that once it was out there, I would have nowhere to hide. But now that it is out there, I find that I don’t want to hide.

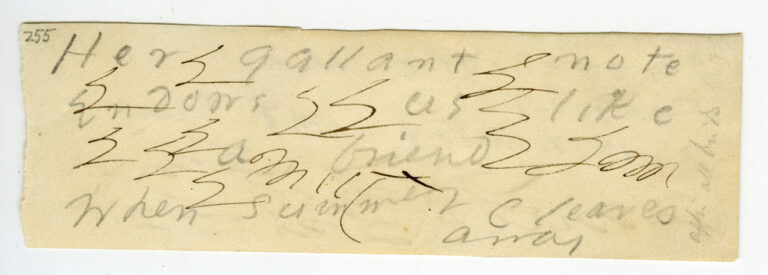

For me personally, one of the very best things that has happened since the book came out is that I have heard from Shane himself and he loves it too. He said, “I know you wrote this out of love and pain.” Indeed.