The Book You Didn’t Know You Needed

Guest post by Greg Schutz

The advent of another holiday season reminds me that, as readers and consumers, it’s easier than ever these days to get what we think we want. Looking for Jonathan Franzen’s new novel? A couple clicks, a couple keystrokes, and it’s on its way to your doorstep. Searching for the perfect gift for a friend who enjoyed Freedom and The Corrections? Amazon provides a variety of tools to lead you to your friend’s next big read, from discussion boards to other shoppers’ wish lists to the ubiquitous (and occasionally inscrutable) “Customers Who Bought This Book Also Bought.”

One upshot of the internet era is that books are now indexed by a variety of associative methods, meaning that the book-buying process has never been more efficient. If you can provide search parameters, you’re practically bound to swiftly find what you’re looking for.

Of course, this presupposes that you know what you’re looking for. It devalues untargeted browsing in favor of targeted shopping. In other words, if it’s easier than ever for us to get what the book we think we want, it’s harder than ever for us to find ourselves gratefully surprised by the book we didn’t know we needed.

I’m far from the first to make this observation, I know. And serendipitous discovery is still possible in the internet era: as an undergraduate, for example, I discovered the fiction of Frederick Busch by mistyping an Amazon search for Richard Bausch.

Still, it’s hard for Amazon or any other website to replicate the experience I had the first time I visited the John K. King bookstore in Detroit.

A visit to John K. King has become one half of a Detroit afternoon that is my guaranteed cure for the dreary-gray-Michigan-wintertime blues, the other half being the Longhorn sandwich from Slows Bar-B-Q over on Woodward. After stuffing myself with the best barbeque brisket in the upper Midwest, I love to wander the John K. King stacks, four sprawling stories of floor-to-ceiling shelves located in a former glove factory–drafty and cold, lit by sputtering fluorescents and flyspecked windows, the air thick with the stale cinnamon scent of old books. Thousands and thousands of old books.

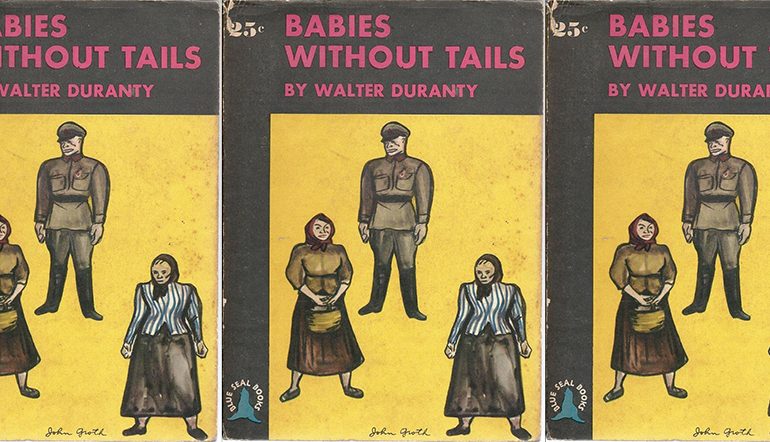

As I wandered the paperback fiction section two winters ago, a squat little book with a funny title caught my eye: Babies Without Tails, a story collection by Walter Duranty. The cover featured John Groth‘s caricatures of two Russian peasant women and a Soviet army officer–stout, vaguely simian-faced folks sketched in thick penciled lines and crudely colored. The copyright date was 1937. A quick perusal of the stories revealed that each was concerned with the penetration of new Soviet ideals into traditional Russian village life, as observed by a Westerner.

I was immediately smitten, to say the least.

I still count Babies Without Tails as one of my luckier used-book finds–but not for the writing itself. Duranty’s fifteen collected pieces read more as fables, really, than as short stories, as their titles (“The Brave Soldier and the Wicked Sorceror,” “The Thrifty Peasant and the Precious Mattress,” “The Wife Who Lost Her Patience”) suggest. The political clout of the local village Soviet stands in for the magic and dei ex machina of folk tales. The best of these tales offer up portraits of a rural Russia in which old superstitions and traditional activities are coming into conflict with new revolutionary ideals.

This single theme quickly grows monotonous, however, as in story after story the instruments of Soviet justice hack through the problems of the peasantry like a blade through the Gordian knot, their machinations efficient but often inhumane. Intriguing at first, the sheen of these stories is quickly dulled by repetition. In addition, Duranty’s occasional attempts at magical realism usually end up sounding merely silly.

Despite all this, the book continues to fascinate me as a historical artifact. Walter Duranty, I’ve since discovered, was not only a Pulitzer Prize-winning foreign correspondent for the Moscow bureau of the New York Times in the 1920s and 30s (and an apparent devotee of Aleister Crowley), he was also an extremely controversial figure: a vocal apologist for Stalinist policies whose sympathies led him to turn a blind eye upon famines, purges, and rigged trials. His explanation for the worst of Stalin’s actions? “You can’t make an omelet without breaking eggs.”

Learning these things about Duranty has drastically changed my reading of his fiction. I’m amazed by how Babies Without Tails–with its backwards, superstitious peasants and steely, ineluctable Soviet justice–confirms the popular assessment of Duranty, while at the same time subtly complicating it. After all, the stories show an awareness of the challenges that faced residents of rural Russia as they adapted to new socialist institutions. And that Soviet justice Duranty keeps depicting often feels mechanized, faceless, and cold.

All this, from a chance encounter in a bookstore.

Part of the power of bookstores comes from their lack of indexing, their inability to precisely target consumers with particular products. When gathered together, physical books–paper, ink, and glue, piled one atop the other or lined in row after row–can enrich our intellectual and emotional lives in ways that we could not possibly anticipate. To be able to wander in directions more aimless than rigid paths of hyperlinks can provide is a power both vital and endangered.

Where do you go when you want to wander? Which bookstores, libraries, and friends’ shelves do you like to browse? What are some of your most memorable and serendipitous finds? Let’s share some of the books we didn’t know we needed.

This is Greg’s thirteenth post for Get Behind the Plough.