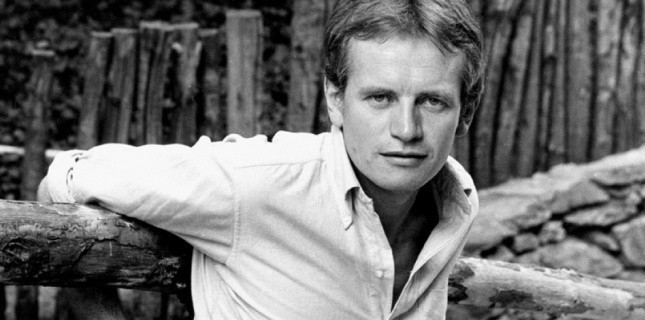

From Manic to Magical: Reflections on Bruce Chatwin

It took me less than five minutes via Google Maps to find where English travel writer Bruce Chatwin had lived during his time Edinburgh. I’m not sure what insight I had expected to gain by tracking down where he stayed during his unhappy tenure in the city, but given that so much of his life and travel writing were dedicated to tracking down his own ghosts, it felt like a necessity. It was plain, nondescript — no plaque, which was a bit of surprise, given the myriad of homages to literary greats that can be found around the city. It looked, in short, like the type of apartment a person takes when they have no intention of staying for long.

It took me less than five minutes via Google Maps to find where English travel writer Bruce Chatwin had lived during his time Edinburgh. I’m not sure what insight I had expected to gain by tracking down where he stayed during his unhappy tenure in the city, but given that so much of his life and travel writing were dedicated to tracking down his own ghosts, it felt like a necessity. It was plain, nondescript — no plaque, which was a bit of surprise, given the myriad of homages to literary greats that can be found around the city. It looked, in short, like the type of apartment a person takes when they have no intention of staying for long.

Both Chatwin’s route to Edinburgh and his ascension to becoming the darling of travel literature were anything but linear. He did not formally enroll in university until the age of 25, deciding instead to work at Sotheby’s in London as a porter after high school. Chatwin quickly climbed the ranks and served as an expert of Impressionist art, a time which he described as consisting of “flying here and there to pronounce, with unbelievable arrogance, on the value or authenticity of works of art.” Contradictions like these would come to dominate Chatwin’s life and his work. How did he reconcile his love of collecting art and archeological oddities with his professed commitment to being a nomad? How was it possible that the same person who wrote grimly about the tendency of material items to tether us to specific places was able to finance his trips to Afghanistan by illegally smuggling out excavated objects?

In Patagonia, the book that made Chatwin famous (or as close to famous as a travel writer can be), involves a journey to recover a lost family artifact — a mylodon skin (an ancient prehistoric sloth-like creature). Many of his journeys began with only the vaguest of intentions — the trip to Australia that would eventually become the book The Songlines was ostensibly for the purpose of “learning more about Aboriginal culture.” Accordingly to lore surrounding Chatwin, the only indication Chatwin left of his intention to go to South America was in the form of a telegram: “Have gone to Patagonia.”

To some, Chatwin’s work and perpetually restless spirit are an indispensable part of any journey. To others, Chatwin was a sort of cultural imperialist, an English dandy who was interested solely in misrepresenting the stories of the people he met for his own personal gain. Chatwin the narrator comes across as almost ethereal; his disposition is one of removed, composed indifference. It is the voices of others that pervade his writing — whether they’re Welsh farmers in Patagonia, or erudite Russian immigrants in Australia.

Nevertheless, it was the very people Chatwin wrote about that would repeatedly contradict him, accusing him of either misrepresenting events or blatantly lying. Chatwin himself would admit as much, saying “A lot of this is fiction. . . . a lot of this is made up. . . . But it’s made up in order to make a story real.” One immediate (and rather humorous) example takes place in his book The Songlines. Describing an encounter with a snake, Chatwin writes, “For myself, I rigged up a ‘snakeproof’ groundsheet to sleep on, tying each corner to a bush, so its edges were a foot from the ground. Then I began to cook supper.” After being tracked down by Chatwin’s biographer Nicholas Shakespeare, the people Chatwin met in Australia clarify that Chatwin was absolutely terrified of the snake, and had essentially begged the people around him to set up the snakeproof ground sheet. Far from the cool, detached observer, fellow writers and friends of Chatwin describe him as perpetually chatty, often nervous and high-strung, and consistently in danger of brimming over the edge of his own manic vivacity. He aptly earned the nicknames Chatterbox and Chatty Corner.

Chatwin would consistently forsake the national for the unabashedly provincial in his writing, casting aside established fact for myth and peculiarity. His visit to Patagonia falls just sort of being explicitly magical, and wherever he chooses to write about distinctly become “his,” which is to say, Chatwin’s Patagonia and Patagonia as a land mass are two entirely different places. A teacher’s report from his last year of high school would confirm as much: “He finds difficulty in remembering facts and only the bizarre or really trifling appeals to him. His historical approach is far too free as yet and he must try to control it more carefully… Too often it school, it seems, and in preparation, he is led astray and his mind goes off on a tangent, usually interesting but usually irrelevant.” Far from being a weakness, this is what makes Chatwin’s writing enchanting. His knowledge of the bizarre and the anecdotal is expansive, and his ability to economically describe what he finds (or what he purports to find) was strengthened by his years spent writing copy for for-sale items at Sotheby’s.

What began as a fantastical quest to find a replacement for a lost family relic ends with Chatwin finding some dung in a cave, but he was always more interested in the journey itself rather than the stated reasons for said journey. He is one of very few travel writers who is as admirable for the lucidity of his prose as for the story he tells. Chatwin lived a strange, manic existence characterized by competing and wholly contradictory passions, but his fidelity to the sheer wonder of traveling to a hitherto unknown place is indispensable. My next journey is in a few weeks, and in one way or another, Chatwin will be with me.