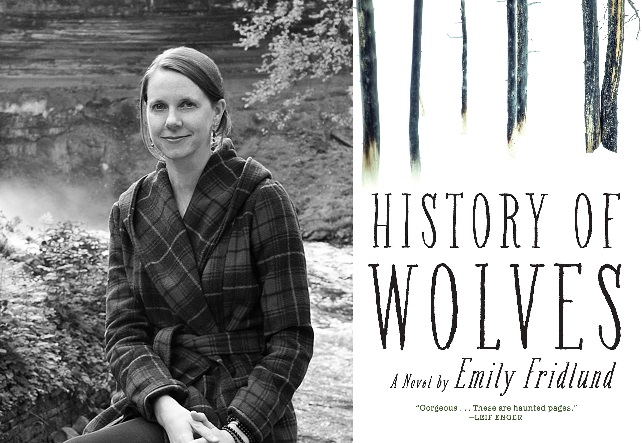

Rural Pride in the Walleye Capital of the World: Emily Fridlund’s HISTORY OF WOLVES

Photo courtesy of Doug Knutson

When fourteen-year-old Linda tells her teacher that she wants her local history project to focus on wolves, giving Emily Fridlund’s novel History of Wolves its title, there’s some eye-rolling in response. Wolves, he thinks, fall into a category along with horses of teen girl obsessions. But Linda’s admiration of wolves has little to do with what they are and more to do with what they’re not. “Wolves have nothing at all to do with humans,” she says. “If they can help it, they avoid them.”

This echoes Linda’s own existence. Some of it is her age; she’s unsure how to interact with her friends, or adults, or even children due to her shifting new role as young adult teenager. Some of it is from her setting, though, isolated as it is from general civilization. The small town of Loose River, somewhere in northern Minnesota, defines so much about her life. It’s a town where the two key descriptions of Christmastime are “competing nativity scenes” and the “strings of colored lights up and down Main Street.” Linda thinks in terms of natural geography: her friend lives “in a trailer three lakes over.” When another character forces her to think about what she truly knows in a grand, philosophical, cosmic sense, she thinks about the land around her house; the trees, the fish, the smokehouse. This is what is stable in her life.

Her parents fall outside of what she knows, existing as vaguely benevolent forces who worry and instruct from a difference. Like all parents, Linda’s mother wants more for her child. When Linda asks for permission to babysit overnight for a newly arrived neighbor, her mother asks, “She’s nice then?” but Linda hears the true meaning of what’s under those words: “She’s not from around here, right?” There’s a simultaneous desire for Linda to both fit in with her surroundings and to transcend them.

But Linda isn’t sure she agrees with this desire. Linda isn’t sure about a lot. She remembers a few hazy, early years of childhood spent in a failing commune, the ruins of which Linda’s family now lives on the edge of, scavenges from. Kids at school call her “commie.” She is old enough to understand the meaning of this: being raised communally with other children and then being narrowed down to a family unit with two specific parents puts their biological relationship in questionable territory. She understands them in a way, you get a sense, that they don’t understand themselves, like when she describes her mother as having “traded whatever hippie fanaticism she had left for Christianity.” A compromise, a contrast.

The story in this book is told through a series of contrasts. The opening scene involves a new teacher, one who had “come from California,” an almost unimaginably far-off place. Linda’s and her parents’ past in the commune is contrasted with the small-town reality present, which in turn gets contrasted with the lived experience of Paul and Patra from the city. The narration also uses the future to show what possibilities and alternative paths always existed, are always narrowed down, by telling us what lies ahead for both Linda and the people around her. These breadcrumbs of future Linda narrating help us see around the limited perspective teenage Linda has and are essential to telling the story.

The contrasts work especially well in the main plotline, which involves the neighbors Linda babysits for. They’re quintessential city dwellers. Leo’s an astronomer of some stripe and writes books, while his young English major wife, Patra, edits them. Their young son, Paul, is a strange child, but taking care of him gives Linda a sense of satisfaction she doesn’t seem to find in any other relationships in her life, except with nature. Linda knows, and so the reader knows, that something is off about this family, but it’s easy for her to chalk it up to their differences—oddity as an import from the city. And so Linda gets to take a lot of pride in being around them. She can recognize and understand the loneliness Patra feels, having been unprepared for the isolation in Loose River. She can teach Paul the names of the birds and the trees and show him beavers’ dams. It fills her with purpose, with confidence. Fridlund deploys this confidence masterfully, because the reader can watch in semi-horror as Linda gawks at the newcomers’ lack of understanding of her world, but totally misses warning signs because of her lack of understanding of theirs. In a way, they’re speaking past each other in this richly tense way that makes the other shoe dropping happen in slow, excruciating motion, full of dramatic irony that a teenage protagonist uniquely makes possible.

History of Wolves was released in January and is Emily Fridlund’s first novel.