The Alchemy of Poetry Plus Criticism

What is the goal of poetry? Is it to make music with language? To express feeling? To make an argument? It’s likely, for any given poet, to be at least one of these things—and possibly all.

And the goal of criticism? To analyze. To investigate. Like some poetry, it also argues, but usually that’s where comparisons between the two genres end.

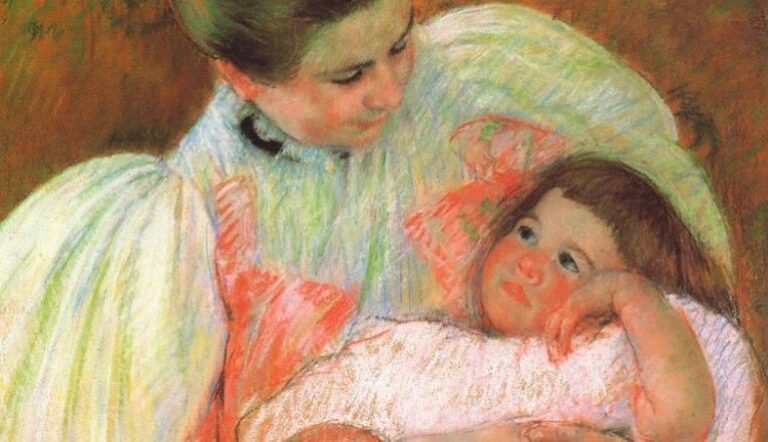

My first exposure to the hybrid genre that combines the critical essay with the lyric movements and methods of poetry came when I heard Maureen McLane read from her National Book Critics Circle Award-nominated book My Poets. That night, McLane read from a chapter called “My Elizabeth Bishop / (My Gertrude Stein).” I don’t remember how McLane introduced the audience to the book’s project, but various reviewers describe the book as “experimental essays” or “part memoir and part criticism.” My Poets foregrounds what most criticism only briefly (if at all) acknowledges: that a writer’s desire to critically explore the work of another writer often springs from a personal source. The writer-critic wants to explore the work that has shaped them personally, or that their own creative work is in dialogue with. In academia, especially, we are groomed to believe that there is only one method of exploration. McLane’s reading was the first time I realized that this wasn’t the case.

Sitting in an auditorium in Belfast, I laughed at first, along with others in the crowd, as McLane began reading “My Elizabeth Bishop / (My Gertrude Stein).” Having just studied Stein the year before, I immediately recognized McLane mimicking Stein’s style in her essay. It begins with a college-age McLane struggling to find a topic for her senior thesis. She wants to write about Stein, but doesn’t feel her understanding is deep enough:

I was falling off the edge of Gertrude Stein and there was no ledge for me no stone to stand on in Gertrude Stein.

All that time.

Why did I want to be made by Stein.

She is of course very fine. Everyone thinks so except those who don’t and many don’t.

She is of course ridiculous until she’s not.

McLane goes on to talk about moving from Stein to Bishop as the topic of her thesis because Bishop is more manageable, easier to comprehend: “I thought I could read Bishop and know that mind and make it mind my mind.” The contrast between the two poets’ ease of digestibility is connected, for McLane, to their sexuality. Both poets were lesbians, but Bishop kept this out of work published in her lifetime, where Stein did not. This, too, resonated with the young McLane.

By the end of the evening I was aware that I had experienced something groundbreaking, but I didn’t necessarily recognize the scope of what was possible in what I had heard. It wasn’t until I encountered a second example in this genre—Linda Russo’s To Think of Her Writing Awash in Light—that I realized how much more depth and engagement could be possible when combining the tools of poetry with those of critical analysis. Russo’s 2016 book is labeled as “lyrical essays” and perhaps even more than McLane’s book, it draws on poetic strategies to analyze the work of five women writers. (Fascinatingly, it begins with an epigraph from Gertrude Stein: “Analysis is a womanly word. It means they discover there are laws.”)

Russo’s book is particularly interested in the relationship not just between the writer-critic and the work she admires, but in how we can engage with the work through the materiality of what is left to the readers. In the case of Emily Dickinson, for example, we have the Dickinson House. We have her desk at Harvard. We have the envelopes on which she wrote.

In Russo’s fascinating meditation on Dorothy Wordsworth, Russo retraces Wordsworth’s prolific walks, lifting words from her journals to emphasize the physicality, the body, at work in the garden, in the field, on the footpath:

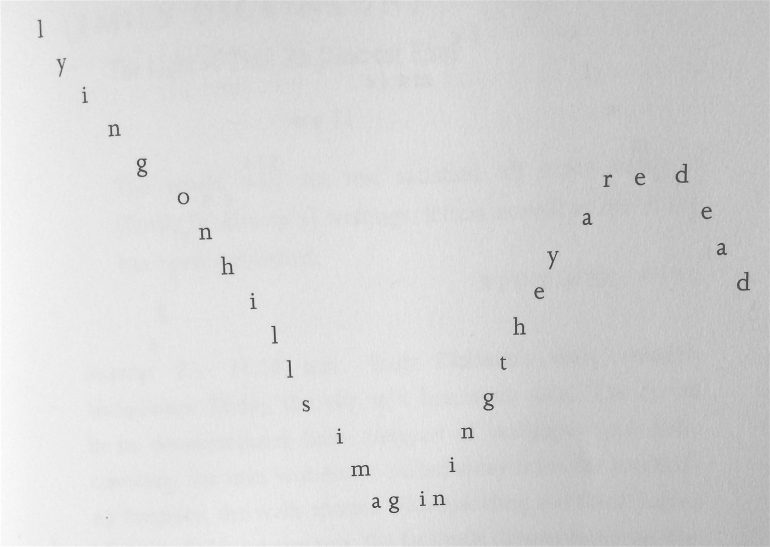

Moonlight home them solemn lemon-thyme moon

One lovely moonlight lemon-thyme

Of solemn clouds lemon-thyme reflection

Night shone planted green returned

Later in the essay, Russo even turns to concrete poetry to recreate the meandering shape that Dorothy and William took together on walks.

For Russo, the movement of Dorothy Wordsworth’s body in nature links to the way that William experienced it through his poems; she mediated for him, too, by being his secretary and sounding board. And these natural details (often deleted for being “trivial” by editors) help mediate for Russo how she experiences Dorothy Wordsworth’s work.

One of the great pleasures of hybrid work is that it is more than the sum of its parts. In this case, McLane and Russo bring poetry and criticism into a union that allows the resulting work to be capable of things that neither seems to be able to do on its own. This alchemy transforms traditional criticism into something with more urgency and higher stakes, providing a window into not just how a canonical writer matters to the world, but how that writer comes to matter individual by individual, speaking down to each reader uniquely through time.