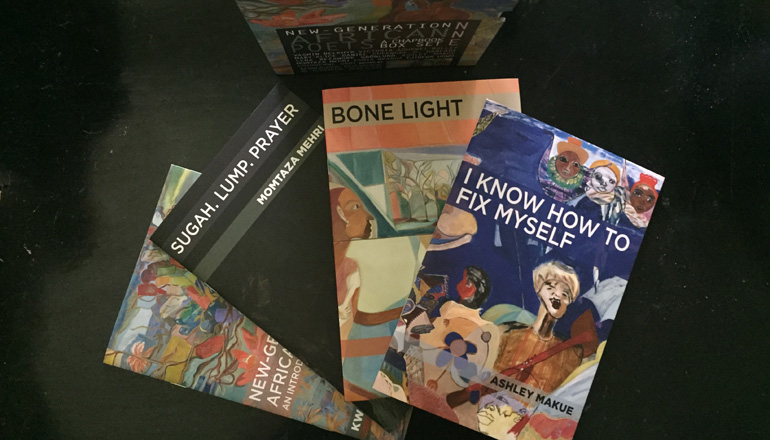

Three Chapbook Reviews from the New-Generation African Poets (NNE) Box Set

The chapbook box set New-Generation African Poets (NNE), edited by Kwame Dawes and Chris Abani, is the fifth of its kind, an annual project of the African Poetry Book Fund, produced by Akashic Books. The set consists of ten self-contained chapbooks by poets either living in Africa or of African heritage. In the first part of the introduction, Dawes explains this choice to accept and promote work from both: “By tackling these two goals at the same time, we have been enacting the larger principles of Pan-Africanism with the caution of not attempting to totalize the experience of the African people.” I chose three from the set to write about this month.

Bone Light by Yasmin Belkhyr

In his part of the box set’s introduction, Dawes muses on “the ways in which these poets root the emotional and intellectual explorations in the body.” Abani finds, in his, “a redrawing of the body both in stasis and in flux,” as a major development for the voices collected here. Yasmin Belkhyr’s Bone Light plays these themes out with its highlights of the relationship between memory, dreams, and reality and a certain starkness of physicality that exists in all three realms and their overlaps and in-betweens. The opening poem, “Surh Al-Fatiha” (also the title of the first chapter of the Quran) evokes the speaker’s first memory wherein “a man slaughters a goat in my bathroom.” A reflection on how this might affect a child-turned-adult’s worldview follows: “I couldn’t list all the terrible things we do to one another. I remember the goat kicking out, frantic.” One of the things Belkhyr does best is move seamlessly from image to reflection back to image, letting the reader connect the dotted lines she has so exquisitely traced.

Belkhyr is a master of the short, striking sentence, pacing these prose poems with a parade’s fluidity and halts: “There are so many bodies of mine that I haven’t claimed yet,” she begins in “Eid Al-Adha,” a poem after Luther Hughes that takes its title for a Muslim holiday. She continues, “So many versions, so many lives. Fat purple figs. When I speak of bodies, I mean: I’m afraid of mine. I mean: I wonder what yours is capable of.” In addition to the human body, dogs, teeth, phone calls, what it means to be a sister, a daughter, or one’s own reflection in the mirror all reoccur in this chapbook, and each time with new weight, new light.

Sugah. Lump. Prayer. by Momtaza Mehri

Tijan M. Sallah’s preface to Sugah. Lump. Prayer. identifies Momtaza Mehri as “a physical expression of the Red Sea’s demographic hybridity,” and Mehri’s poems enact this. In “buttercream bismillahs,” a bed for lovers spans “the split lip of an ocean” (line 6). The pain of this division is felt throughout the chapbook, as the next poem “Transatlantic (take one),” confirms, “home is where the hurt is” (line 3). The speaker does not mean to desecrate the name of her home here. These lines, instead, ache with the distance between lovers and the difficult nature of transnational identity. “Duty free and glazed biscuits” (line 11) remind the speaker of her lover, but discussing them also is an opportunity for that split identity in terms of home and place to come forth. She says of the biscuits, “They don’t make ’em like that in my country. / Not that one. I mean, my other country. I mean, I live in the exported script” (lines 12–13). It is lines like these, taking the everyday in relation to the speaker’s identity toward moments of pure metaphorical beauty that make this chapbook sing.

The music of it also comes from its devotion—the “prayer” of the title is no accident. Many of the poems are named for the Muslim times of prayer. In “zuhr,” (the prayer after midday), the first part of the poem “Clockwise,” the speaker implores, “I want to / say we are more than our geographies of loss” (line 6). The other parts of the poem are numbered; in “labo,” (two) she begins, “What is there to write about after exile? / After this dress of loose skin / and zip codes” (lines 8–10) echoing with clarity the silence forced leaving perpetuates that many try to express, yet adding the idea of carrying one’s own body around as weight, as proof. “saddex” (three) reads: “Trust is a vowel sound away from power / Trust is willing a boat to shore / Power is not having to. Even our language mocks us” (lines 21–23). Mehri seems to always be writing about herself but at the same time always about the largeness of the world, all its seemingly scripted mistakes, conflating the two smoothly, as if melting the lumps of sugar from the title into something we can “make a castle out of / this bottled sigh / they call living” (line 28–30) as the speaker says in “I believe in the transformative power of cocoa butter and breakfast cereal in the afternoon.”

I Know How to Fix Myself by Ashley Makue

Ashley Makue’s chapbook ends on a truce—in the poem “peace offering,” she writes, “these are the days / of the sweet treaty.” This is an apt moment of compromise or perhaps maturity for the speaker; love, for most of I Know How to Fix Myself, is fire, asphyxiation, war. The speaker discusses her own and others’—her mother’s, her aunt’s, her best friend’s—ideas of love in these poems. The ending treaty may be the “fix” the title indicates, meaning the brokenness it implies is in the speaker’s romantic relationships. But the title poem suggests it is something hereditary, not something easily discarded:

my great-great grandfather begets my great-grandmother. my great-grandfather begets my grandmother. my grandfather begets my mother. my father begets a ghost.

In the preface, Honorée Fanonne Jeffers identifies this brokenness as ancestry and calls the chapbook “a lyric biography, a daughter’s witness to the world of men and women”—possessed and created by men, inhabited by women. Though the speaker of “seasons of alone” might look like her father, it is in her mother’s footsteps she follows: “falling not too far from your mother / from hollow // from lonely” (lines 15–17). In a set of three poems each featuring the speaker’s mother in the title, life exposes its contradictions and injustices piece by piece. In “mom goes,” important lessons are learned but the world won’t always reflect their truths: “they say that love is not supposed to hurt / I think they mean that god didn’t get angry / and drown our body / cause / effect” (lines 24–28). In “mom’s on fire,” the mother’s sexuality is understood through metaphors of war and violence: “she is a sunken dream / her triggers set against herself // my mother is a war zone” (lines 7–9). Next, in “mom’s language on fire,” the speaker learns certain words have double meanings in her mother’s language: “fire also means zeal” (line 2) and “quiet also means dead” (line 32). This insight creates a fluidity within her English, and therefore a new, double meaning for the reader when these words repeat throughout the rest of the chapbook. Language itself is a heritage, readers discover—and through it, peace may be possible.