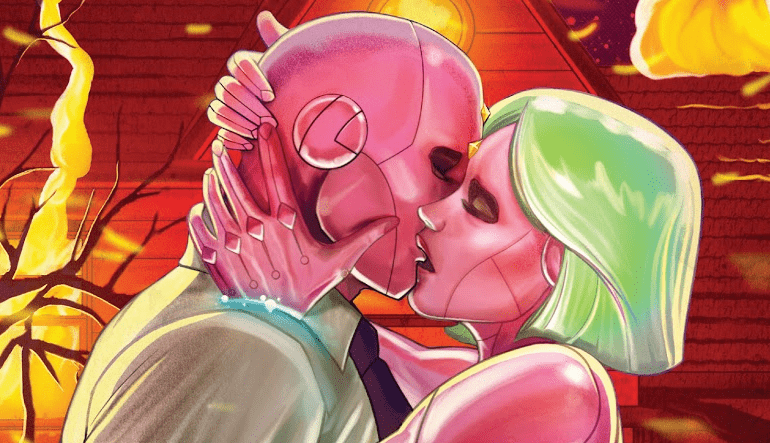

Breaking Under the Weight of Formula in The Vision

There’s often this narrative expectation built into mainstream superhero comics. Maybe it’s that we’ve been trained on the Marvel movie formula, but when we talk about these types of comics from companies like Marvel and DC, it’s about bad guys, playground morality, and action scenes. These aspects have their place—the world has bad guys that we need to believe can be stopped, morality isn’t always relative, and catharsis in art is important—still this expectation controls the vision we expect these stories to conform to.

If I were to tell you a story was about a nuclear family moving to a quiet suburb fifteen miles west of Washington, DC, you’d probably sigh and expect literary fiction—something like by Michael Chabon or Philip Roth. If I were to tell you then that a story was about a family of five robots moving to a quiet suburb fifteen miles west of Washington, DC, you’d know it was science fiction.

But if I were to say a story was about a family of robots moving to a suburb with one being a character who was in a movie last summer that made $1.15 billion, you’d know we were talking about superheroes.

The recent Marvel comic series The Vision by Tom King and Gabriel Hernandez Walta shows that while genre might act as an imaginary (and often arbitrary) partition, the nature of what these partitions hold and why we hold them can be meaningful.

In the twelve-issue miniseries, the Vision (a robotic human built by the villain Ultron to destroy the Avengers only to turn on his master and become a hero back in 1968) builds a family—a wife from the brain scans of an ex-girlfriend and twin teenagers from a combination of both their brain patterns—and moves to a quiet neighborhood to live a human life.

There’s no central conspiracy over these twelve issues. There’s no supervillains bent on ruining their life or characters with problems managing their personal obligations with their superhero lives. This is a story without any heroics and barely any super but is instead a fiction story about a household and a suburban life. A story that, as the comic tells us from the beginning of the first issue, is doomed.

Across the first few issues, there’s an ominous narrator framing every pastoral and quiet scene. Our introduction to the robotic family is from a visit from some neighbors across the street, dropping off cookies and being shown the interior spaces of the Visions’ home. The narrator lets us know before five pages in that “later, near the end of our story, one of the Visions will set George and Nora’s house on fire. They will die in the flames. George’s last thought will be of Nora. How he found his true love and regrets little of what came after. Nora’s last thought will be about the water vase of Zenn-La. She will wonder why it was empty.”

Tom King writes familiar arguments. A phone call between husband and wife about who can be home with the kids and when. Teens getting bullied in school and learning Shakespeare. The narrative is a specific type of fiction but each of these conversations happen in strange robotic tones. Vision explains to his wife the semantics between describing the neighbors as seeming nice or seeming kind with Vision arguing that “‘nice’ due to its ironic interpretation, has a more flexible connotation. As such ‘they seem nice’ has a proper meaning of they may be nice or they may not be nice.” The contents of a conversation are easily relatable for anyone ever stuck in a pedantic argument but spoken in a completely inhuman way.

We can never escape that what we’re seeing is a facsimile of a real conversation. The Vision, by telling a story about a superhero comic book family trying to lead a normal life, also shows us a conversation about a mainstream comic book fiction trying to follow literary fiction.

As the Visions try to lead their normal life, the super and thus comic book aspect of their lives try to invade. A supervillain from a past comic series will blow down their wall, shouting and attacking over information and histories we’ll only see or really understand outside of this story. Another hero will show up even if only for a brief cameo and with each introduction serves as another stake driven into the foundation to split their narrative structure as the superhero comic structure invades and breaks down the story like an infectious virus.

This is a story about facsimiles. The Visions as a human family is a lie. Their imitation is conscious as they hope that being a facsimile of a normal family will make them one. Facsimiles are never the real thing, however, and they bend under the weight of expectation, and by the end of The Vision the narrative’s done the same. The idea of a pastoral suburban narrative in a superhero medium crumbles away. There’s this acknowledgement that some narratives can’t survive in some forms, whether that’s the weight of marketing, continuity, or time, there’s an intent or nature behind certain character narrative that only allows for so much mobility. Doing else is becoming a facsimile, and a facsimile can hold only so much value.

In The Vision, in their home is a vase made of floating water, the Water Vase of Zenn-La. The vase sits on a pedestal empty across the entire series because the water of Zenn-La, while beautiful, is completely toxic to every known species of plant life—a vase that can hold no flowers. So then at what point is it still really a vase?