Writing Appalachia

Southern Appalachia, like many rural places, is often depicted as a terrifying wasteland inhabited by meth-riddled, slack-jawed locals lurking behind Dixie flags in burnt-out single wides. Then again, you might know it as the idyllic (and unpopulated) “unspoiled” place where clear streams flow freely between rhododendrons and a canopy of old growth forest. For those of us who live here, of course, it’s just home.

One of the finest contemporary writers mining the extraordinary diversity of this complicated landscape is Ron Rash. Rash, whose work sprang to national attention with his novel Serena, writes almost exclusively of these mountains and her foothills. In a career that hasn’t yet spanned twenty years, he’s published seven novels, four volumes of poetry, and six collections of short stories, while serving as the Parris Distinguished Professor in Appalachian Cultural Studies at Western Carolina University in Cullowhee, North Carolina. He’s twice been a finalist for the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction (in 2008 for Chemistry and Other Stories, and in 2009 for Serena) and earlier this year was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship.

Rash’s characters inhabit a landscape shared with ghosts, both living and dead. His novel The Cove opens with a schoolgirl’s memory of her teacher passing around the dead body of a Carolina parakeet, a colorful bird now long extinct. Even at the time of the story, it was already nearly gone, shot by farmers protecting their crops. Many of Rash’s characters are similarly on the verge of extinction, but none of them have truly left. In his poem “Spillcorn”—the name itself a memory, the way places are named after events that no one later is left to recall—the narrator imagines a “kinsman” walking along the same road a hundred years earlier, turning the pages of the book that the trees he’s felled would become. His characters reach back to Scotland, where so many of the settlers of these mountains originated. And they run downhill to the mills of the piedmont, where Rash himself was born, and back uphill again to the present-day residents of these mountains.

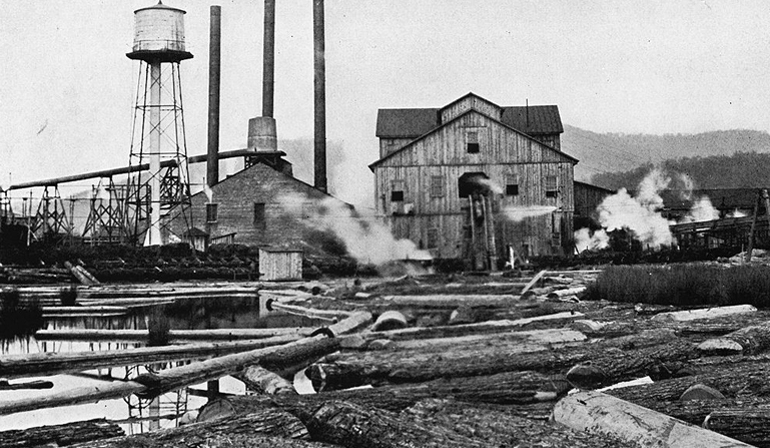

Time isn’t linear in these stories, but folded into itself. It’s carried in ordinary objects and arcane linguistic mannerisms that retain the stubborn isolation of another generation. In the “brightfulness” of sunlight, and phrases like “I don’t misdoubt” to mean trust, and “I’ll spell you” to mean rest. Neither, for all the evidence thereof, will you find the usual passive depictions of poverty so often associated with this region. In Serena, for example, the exploitation of the mountain’s natural resources (its forests, which were stripped by the logging industry) resulted in the wealth of a select few, while hundreds more sold their labor for pennies. In the poem “Tobacco” (published first in Eureka Mill and later, slightly revised, in Waking) Rash reminds us of a time when wealth meant a “land generous enough, apple trees drooping their fruit to our hands, woods and streams thick with squirrels and trout.” This abundance is only free however for people who don’t need money: once “the fence laws passed and taxes rose, we needed cash crops to keep our farms.” The scarcity of “cash money” is a persistent reality which the richness of the land can’t displace. It’s cash money that provides the means to live in this land on a year of drought, flood, or when a late freeze destroys the crop. It’s the promise of cash money that leads people down to the mills. There, they’ll dream of home but choose not to return for they’ve not forgotten the harsh realities of this land.

Divides between neighbor and neighbor in these stories are more likely to be the four-hundred-year-old schism between Catholic and Presbyterian, or whose family sided with the Union or the Confederacy during the Civil War. A different split separates those with access to books and education, and those without. But all these divides and schisms make up one common community.

Here we see what fiction does best, which is to dispel the received narratives about other people’s lives, allowing us a new empathy, a new connection, an opportunity to let go of our own tightly held beliefs about what is normal, and what is strange. Rash said, in a discussion with novelist Elizabeth Kostova earlier this year, that there’s nothing worse for a writer than to have an idea. He’s said elsewhere, many times, that all his writing starts with an image. He follows that image wherever it might lead, and so is open to the surprises it may bring. Over the last few months, particularly since the election, we’ve seen increased media attention on people who live in rural areas, particularly Appalachia. We’ve seen the work of conservative commentator and Silicon Valley venture capitalist J.D. Vance become a bestseller in part on his claims of being a “hillbilly who escaped.” Widely shared op-eds by writers like Frank Rich (“No Sympathy for the Hillbilly”) and Kevin Baker (“The Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless White Mind”) do what Rash explicitly warns against: they start with an idea of what they’ll be about, with a mind to convince rather than discover.

As I walk down the gravel road to my own mailbox this morning, I allow myself to be surprised by the sound of cicadas. Old men seated in front of the gas station, their Styrofoam cups gleaming. Jewelweed sparkles in the ditches between clusters of poison ivy. A black snake, hearing my step, ripples across the road and between the leaf cover. There’s a low murmur of the distant highway, blotted out by intermittent weedeaters, lawnmowers, two-stroke engines of people working hard to keep the wildness of the natural world at bay.