All In: Great Books by Authors Who Immersed Themselves in the Story

Anyone who is a writer is also a researcher. Stories sprung from one’s imagination are not exempt from these duties. Fiction writers frequently write about a time and place they know—think Conrad and the Congo in The Heart of Darkness or Harper Lee and the rural South.

Anyone who is a writer is also a researcher. Stories sprung from one’s imagination are not exempt from these duties. Fiction writers frequently write about a time and place they know—think Conrad and the Congo in The Heart of Darkness or Harper Lee and the rural South.

Similarly, writers become interested in a time or place, pack up their things and do their own primary research. Marilynne Robinson did this for her classic Gilead. Robinson has spent much of her professional life in Iowa, where the book is set, but she still needed to research the “byways of Iowa history.”

Writers of nonfiction have a more obvious obligation to be facts. This once hard, fast rule was bent to its near breaking point most famously by Truman Capote’s “nonfiction novel” In Cold Blood, which blurred the lines between fact and fiction.

There is a subset of nonfiction writers who take research to another order of magnitude. It’s not unusual for nonfiction writers to go where the story is—in a lot of cases it’s required. They spend several weeks or a few months at a location with key characters and then write the story. But some writers go beyond this and spend a pre-set amount of time with a character or at a location. “Immersion journalists” take the next step and insert themselves into the narrative. Once upon a time, this was frowned upon in journalistic circles, but Capote, Hunter S. Thompson and a cadre of practitioners of the so-called “New Journalism” muted critics with their superior writing and voice. Less skilled writers aren’t always able to subordinate themselves for the sake of the story—unless it’s a memoir, in which case the author is the story.

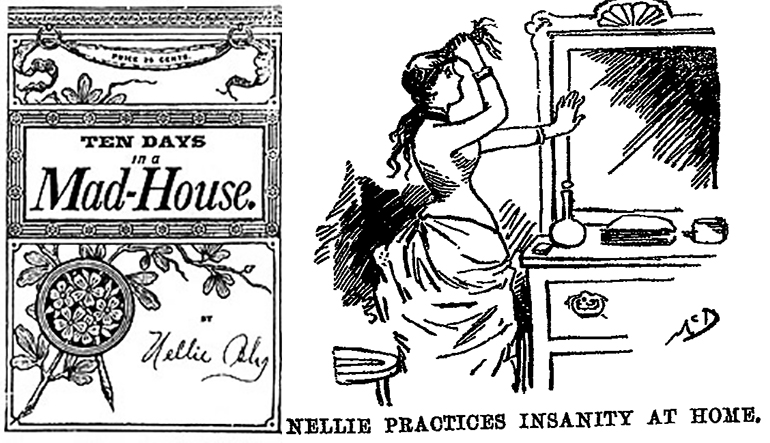

Nellie Bly was the pen name for Elizabeth Cochran. A struggling journalist in the late 1880’s, she got herself an assignment for The New York World by agreeing to fake a mental illness and go undercover at an infamous psychiatric hospital. Unsurprisingly, she encountered horrific conditions for the patients. Ten Days in a Mad-House, based on her experience, put the patients rather than Bly at the center of the story. The work made her a household name and caused the State of New York to change the way it treated the mentally ill.

In The Jungle, Upton Sinclair adopted a similar approach to Bly when he worked undercover in a Chicago meatpacking plant in 1904. The difference between Sinclair and Bly is that the former fictionalized his work. The book was intended to be an exposé meant to highlight the struggles of immigrants. Instead, readers were aghast at the sub-standard way meat was handled. Like Bly, Sinclair’s work led to changes in laws—regarding food safety. Not a small accomplishment, but not the one he desired: “I aimed at the public’s heart, and by accident, I hit it in the stomach,” Sinclair once said.

The immersion approach was an ideal fit for writing about sports. George Plimpton’s Out of My League was the first notable experiment in this genre. As the first editor-in-chief of The Paris Review, Plimpton would certainly have been well-known within literary circles, but Out of My League and his books that followed its model inserted him into the larger cultural conversation. The premise was for him to try out for a major league baseball team. Shocker: he didn’t make the cut. But he had created a new genre in literature. He later wrote books about his experiences with the Detroit Lions football team, the Boston Bruins hockey team, tennis legend Pancho Gonzalez, the professional golf tour, and his sparring with champion boxers Sugar Ray Robinson and Archie Moore.

If Plimpton’s books were the earliest immersive books on sports then Season on the Brink by John Feinstein is the most successful. Feinstein was the college basketball reporter for The Washington Post when he decided the spend the 1985-1986 season with the Indiana University basketball team, who were led by combustible coach Bobby Knight. Feinstein did not insert himself into the story as Plimpton had, but he went behind the scenes in such detail, capturing the ups and downs of a basketball season in a way that hadn’t been seen before. The book did not flatter Knight and he later refused to speak to Feinstein. But his team’s story went on to sell two million copies. Like Plimpton, Feinstein repeated his model covering college football, golf and minor league baseball. But none of his subsequent writing had the impact of the original.

By the 2000’s the immersive genre was set to return to its Bly-Sinclair roots and take on social issues. Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By in America by Barbara Ehrenreich more than did the trick. The book was controversial from almost the moment it was printed. Ehrenreich’s depiction of life on the socio-economic margins has her not utilizing her PhD, but instead taking on a series of low-paying, menial, repetitive jobs. Her supervisors are portrayed in a less-than-positive light and her struggle to make a living is agonizing and exhausting, as anyone who has been in such a circumstance surely knows. Naysayers said Ehrenreich highlighted the negatives, oversimplifying how hard it is to get ahead. Now, her book looks prophetic, a chronicle of income inequality with the working class struggling to maintain what little they have.

Immersive writing is almost a requirement now for long-form writers. Contemporary readers have come to demand thoroughness, accuracy and intellectual honesty. The bar has been raised by the likes of Joan Didion, Annie Dillard, Ted Conover, and Tracy Kidder. What’s the next frontier for immersive writing? The prediction business is a sketchy one, but suffice it to say we’ll know it when we see it.