Resistance at Bryce Dessner and Richard Reed Parry’s Black Mountain Songs

The stage: a raised platform at the back of the stage for instrumentalists; dark risers in front. The perspective makes the piano look like a toy, the cello like a violin propped on its side, the guitar a child’s miniature. When the musicians enter, they too appear tiny. When the aisles fill with children, the singers of the Brooklyn Youth Chorus, we are not surprised.

The stage: a raised platform at the back of the stage for instrumentalists; dark risers in front. The perspective makes the piano look like a toy, the cello like a violin propped on its side, the guitar a child’s miniature. When the musicians enter, they too appear tiny. When the aisles fill with children, the singers of the Brooklyn Youth Chorus, we are not surprised.

Slowly the children make their way onto the stage, singing all the while, their voices clear and soft, the harmonies tilting in all directions. They drift together in such perfect choreography that it looks a gentle mess, a swirl of bodies, each looking like they’re in a dream. “I wouldn’t / embarrass you / ever. / If there were / not place / or time for it” reads the text of Robert Creeley’s poetry–but the composer (Bryce Dessner) has split the text from its sound.

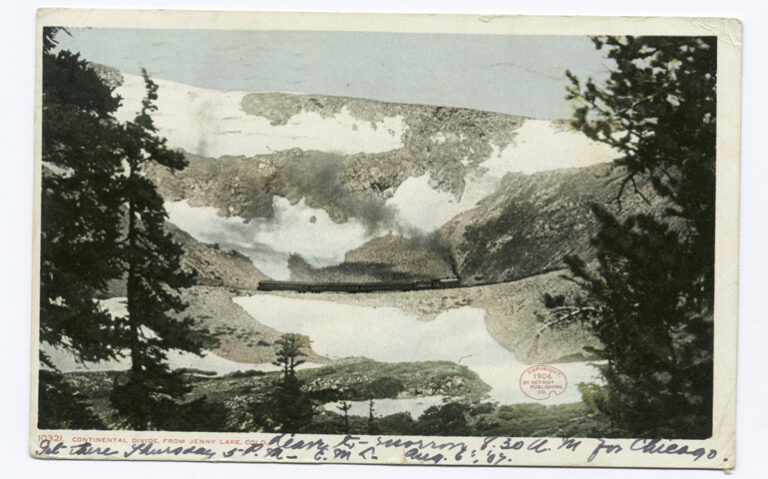

Over the musicians’ platform, black-and-white photographs from a distant generation are projected onto an angular screen. Something about the trapezoidal shape of the screen and the fuzzy images of distant gray mountains brings to mind looking through the backseat of a car window on a long drive. We’re on our way to somewhere. While we’re sitting here on a warm September evening in Asheville, just down the road from the original Black Mountain College campus, it’s easy to feel we’re very far away.

Black Mountain Songs is a intensely collaborative work of composition, choreography, and the choral singing of fifty children. Initially conceived by Dessner (of The Nationals) and Richard Reed Parry (of Arcade Fire), the two invited six other composers to contribute original songs based on the words, ideas, and spirit of the artists of Black Mountain College to the performance. The result is a transformative event that does more to re-create the experience of this institution’s pedagogical experiment in interdisciplinary artistic education than it does to ground us in the history.

This approach would have been met with full approval of those who created the community that was Black Mountain College. This was a school whose curriculum was never intended to be studied, but experienced. This “ethos of community and collaboration” is what Dessner initially sought to bring to life through Black Mountain Songs.

In 1933, Anni and Josef Albers fled the rise of Hitler’s National Socialism for a fledgling institution in the mountains of Western North Carolina called Black Mountain College. While artists and intellectuals were under attack in Europe, the worldwide Great Depression of the 1930s was in full force. Unemployment in the United States was a staggering 25%; those rates were higher for those living in rural regions of North Carolina. For its first years, Black Mountain College was based in what was essentially an off-season rental of Robert E. Lee hall in the YMCA’s Blue Ridge Assembly near Black Mountain, North Carolina.

The Albers spoke not a word of English when they arrived to teach. “Then what will you teach?” a student is reported to have asked. “To open eyes,” was Josef’s reply.

The curriculum of the college was based on John Dewey’s progressive idea that students learn best through direct experience, and that liberal arts and fine arts education must happen both inside and outside the classroom. From its inception, Black Mountain College dissolved the social hierarchy between students and teachers. There were no required courses; students and faculty all participated in farm work, construction projects, and kitchen duties. “Black Mountain’s contribution was that you could live creatively simply by the way you looked at life and the way you lived it. I didn’t learn technique at Black Mountain. I learned a point of view.” said Mary “Molly” Gregory, master carpenter and designer.

There’s a similar simplicity to Black Mountain Songs. “The spirit of learning through doing and emphasis on self-exploration for both teachers and students,” was one of the qualities of Black Mountain College Dessner hoped to convey with the performance. He did this not only through the use of children at the center of the Songs, but by incorporating the bare, graceful, and aging body of the legendary dancer and choreographer Gus Solomons Jr. into the work. The contrast between the flock of gracefully clad children and Solomons’ dancing serves as both counterpoint and gentle mimicry, bringing out the playful qualities at both ends of life’s arc.

Black Mountain College Museum brought this performance of Black Mountain Songs to Asheville as a part of its annual reVIEWING BMC conference. Although it premiered at BAM in 2014, this will be the first time it’s been brought to the Southeast. As I walk across downtown to attend the performance, sixty years after Black Mountain College’s doors were closed, the specter of racial supremacy is rising again in our streets. Our schools and universities are increasingly run by corporate interests which have no interest in the “whole person” of John Dewey’s model. Public funding for the arts is a distant memory. Decisions are being made about nuclear war in secret. Guns have never been more lethal; their sales have never been stronger. What’s the purpose of art in a political time?

I’m trying to explain to my girlfriend something I’d heard in the conference earlier that day, how every event is a collision of decisions. I’m thinking of how vulnerable we are, two bodies in a group of bodies, the way there’s nothing between us and a bullet but air.

We get used to this: the razor’s edge between acceptance and terror.

Many of us have coalesced around the word “resistance.” For all its sibilance, it’s a rough, muscular word. Resist! It’s a hiss, a whisper, a command. Some of us have taken up the banner with a weeping fury, grieving and bereft. Some of us mutter the word wearily, knowing full well that today’s resistance was yesterday’s EST seminar, will be tomorrow’s GOOP conference. At our worst, we use the word as a pout, insulted and aggrieved: this is not how we wanted things to be.

But at our best, the spirit that I’m calling resistance has in it a deeply anarchic joy. It’s playful, unpredictable, occasionally dangerous, and often celebratory. Most of all, it refuses to make sense.

The world is perpetual crisis. It could be said that many of our inherited forms replicate this pattern of crisis/resolution we choose to believe. In times of crisis, it’s harder than ever to let go of received forms. But that’s exactly what Black Mountain College tried to do: create artists and citizens, fully realized human beings who recognize the potential of what they might do once able to set aside the urgency of individual freedom for collaborative ecstasy. There is extraordinary discipline in developing this manner of play, which we might also call resistance.

Black Mountain Songs is a gesture in this direction. It’s never overtly political, but neither was most of the work coming out of Black Mountain College during a time that ranged from the worst of the Depression to the second World War, the ensuing revelations of Holocaust, and the rise of the Stalin’s Soviet Union and McCarthy’s House Un-American Activities Committee. But the very choice to turn from political commentary is itself a political action.

The first political action we ever take is to learn to play with others. The choice to play with others, to delight in the intimacies of collaboration, and to allow the efforts of individual artistry to blur with another’s vision. By placing an undifferentiated chorus in center stage, Black Mountain Songs is a reminder of the role of citizenship: Share space with others. Listen to each other. Trust that your own participation will make all your voices stronger.

I’m thinking now of Robert Creeley and Charles Olson’s projective verse: that is, verse in which form emerges from content, shaped by the anarchic breath rather than rhyme or rhythm. It’s a poetry in which no resolution is possible, and in which movement goes on forever. While the young singers move about the stage in gracefully choreographed movements, images from the college ripple across the screen overhead. And, for a moment, I’m not afraid.

Photo by Steven Pisano