Can Twitter Make Trauma Generic? And If So, What Should We Do About It?

Right before the holidays, I gave a series of readings at an art school in Belgium in which I traced the arc of Trump’s rise through three different essays I’d written between 2013 and 2017. One essay detailed my failed attempt at buying a house for one dollar in Detroit when I was 25. Another essay came from a 2016 book on John G. Zimmerman in which I outlined the concept of American Rust and the rise of populism. And the third essay was on poetry in the wake of Hurricane Harvey.

I finished my talk by highlighting facets of each essay that so clearly (if only in retrospect) were symptoms of this split in the American fabric, this “trauma” I called it, at which point a Belgian academic immediately cut in to say something to the effect of, “I am sorry to interrupt, but Americans do not know trauma. Your millennial generation does not know trauma.” He went on to explain the two world wars, the Holocaust, the dictatorships in Spain and Italy, the Cold War and then got off on a weird tangent on Margaret Thatcher and punk rock at which point he excoriated me for my generation not inventing something like punk rock yet. “I’m on it,” I said if only to lighten the mood a little. The dude did not smile.

And I think it was at this point that I said the thing that kind of set him off, which was the truth: that trauma is not mutually exclusive. That because one generation faced incredible trauma, it does not mean that subsequent generations’ trauma doesn’t matter. The definition of trauma does not drift to fit the most extreme version of that word. In fact, that would be dangerous because it would facilitate complacency (things aren’t so bad now, look at how they were).

As a writer, I’ve been thinking about the importance of our trauma—the very real, needle-pushing trauma of the #MeToo movement, of the interrogation of “post-truth,” of the existential crisis necessary for confronting something like climate change, or (in the case of my own writing) looking at the stories beyond the body counts of the drug war in Mexico.

To me, the trauma is very important—we wouldn’t be having these conversations without acknowledging that trauma. But everywhere, too, we’re constantly reading about the burnout of interrogating that trauma, of trying to initiate change, of self-care, of taking social media breaks, etc. which has me wondering: do we run the risk of becoming immune or numb to other people’s trauma by constant exposure to it? Does trauma ever become generic? And how do we prevent that from happening?

Much in the way some people (government responses, even) shut down in the face of something so existentially large as climate change, we’ve seen the way trauma can be crippling in mass quantities when delivered on a conveyor belt-like system à la Twitter or platforms like it, which are essentially trauma machines these days anyway. But not necessarily because of the quantity of it so much as the way it can be debased (and consumed) in the form of click-bait, or disaster porn, or as a kind of sideshow spectacle which is not necessarily news and not necessarily unique to the internet though very much part and parcel of the Twitter apparatus which is, at its root, a capitalist endeavor that is increasingly thriving on the spectacle of shared trauma—more users, more clicks, more money. In other words, trauma packaged as another gimmick, a shared experience, another thing to consume in the conveyor belt boredom of life.

To this end, I’ve wondered about the fallout of a generic trauma. A trauma in which, say, the anniversary of Sandy Hook passes and no one really cares. Or in which you try to name the last three major American shootings and our responses to those events have become so rote that we literally forget that they ever happened. Not to suggest that one should walk around as an adult in the state of constant trauma, but you have to be able to access the humanity of that trauma in a meaningful way if you’re going to create from it. You have to sink into the nuances of that trauma if you’re going to react with a poem, or a novel, or even a movement like punk rock.

It’s for this reason that the #MeToo movement is illuminating to me as a writer. Its power is in its refusal to become generic. The dynamic nature of the movement is rooted in the specific: voices and stories of women reclaiming their dignity by contributing their subjectivity to a larger chorus that directly confronts rape culture. The same refusal to become generic can be seen in the #BlackLivesMatter movement as well, which is heavily rooted in the stories and dignity of the victims of police brutality and institutional violence. Both of these movements manifested on Twitter, by the way (the machine giveth and the machine taketh). Both of these movements have catalyzed real change with the power of individual stories that can resonate within a single moment, but also endure in a slow-burn manner over time. And the movements are decentralized. They exist everywhere, online and offline.

So, writers have to make trauma specific. Historically, the artist’s role has been to actively seek out the light emitting from trauma, which is just another way of saying seeking out the humanity and dignity in the people around us. It means actively not debasing trauma and instead contextualizing it in the larger spectrum of human experience. It’s remembering that while trauma can be communal, that trauma also affects specific people.

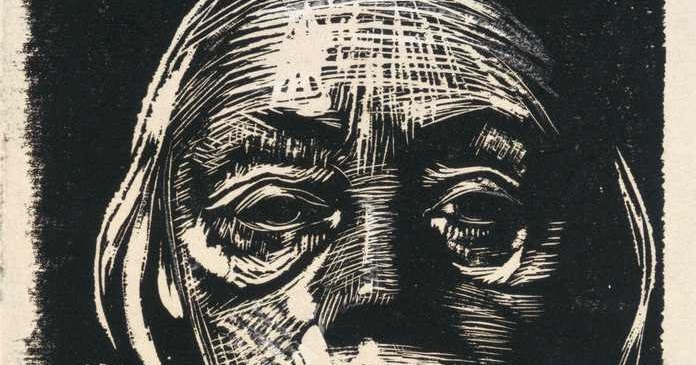

I’m finding myself going back to art museums these days pretty regularly if only to unplug, if only to uncondition my brain. Not to escape trauma, but to reach it in a meaningful way, to see how others have interrogated it outside of the algorithms lenses that shape our perception of it and therefore our reaction to it and the world at large. I visited the Käthe Kollwitz house in Berlin most recently. Kollwitz was a sculptor, printmaker, painter, and lithographer and having lived through both world wars, her entire oeuvre is centered around subjects of despair. And while her most famous pieces are sculptures that are iterations of Mother with Dead Child, some of my favorite works of hers are the woodcuts that are simply dark on light which, even within a woodcut, seem to have incredible movement and expression and agency.

As you look into the subjects of her woodcuts, you can almost feel your gaze returned as if the subjects are saying to you, What do you do now that you’ve seen this darkness? Which is typical of so many of Kollwitz’s woodcuts which later became posters for public campaigns against hunger or poverty or social injustice. On a personal level, I’m increasingly fascinated with how her own work reacts to trauma, but also the way in which dark and light react to each other to convey expression and subjectivity. The stories emitting from those people who are bleeding through the dark.