Cultural Legibility in America’s Dark Chapter

In Jiayang Fan’s recent article, “Buried Words,” which appeared earlier this month in the New Yorker, Fan asks: How literal must a literary translation be? Fan ponders the case of Han Kang’s Man Booker International Prize-winning novel, The Vegetarian, the first Korean-language novel to win the prize, which Kang shared with Deborah Smith who translated the work into English. In the wake of the prize, Kang’s book saw a “…twenty fold spike in printed copies of the book.” Smith became world-renowned by proxy. But then, soon after, Kang and Smith’s success was “…overshadowed by charges of mistranslation,” Fan writes.

Fan details how HuffPost Korea largely dismissed the translation. Charles Yun, a Korean-American professor and translator who lives in Seoul, wrote in The Los Angeles Times last September that Smith’s translation was, in effect, a complete rewrite of Kang’s work, saying it was as if Raymond Carver had been made to sound like Charles Dickens. Smith’s translation, Fan writes of Yun’s view, isn’t “…a matter merely of accuracy but also of cultural legibility.” Fan wonders of Kang’s success and if her spare style, predominant in Korean fiction, would have won over western audiences as readily if Smith had stuck to a less verbose translation, closer to the original Korean prose.

I’ve been thinking, recently, about cultural legibility, especially as it concerns writing about other countries, communities, and cultures—even one’s own. But what does it mean to be culturally legible? And what does cultural legibility mean with regard to writing about or from within one’s own culture? For what it’s worth, I think good, solid, (magical, even) cross-cultural translations exist—look no further than works by Christina MacSweeney, Sophie Hughes, Howard Goldblatt, or Efrén Ordóñez. I think cultural legibility outside of one’s host culture is possible.

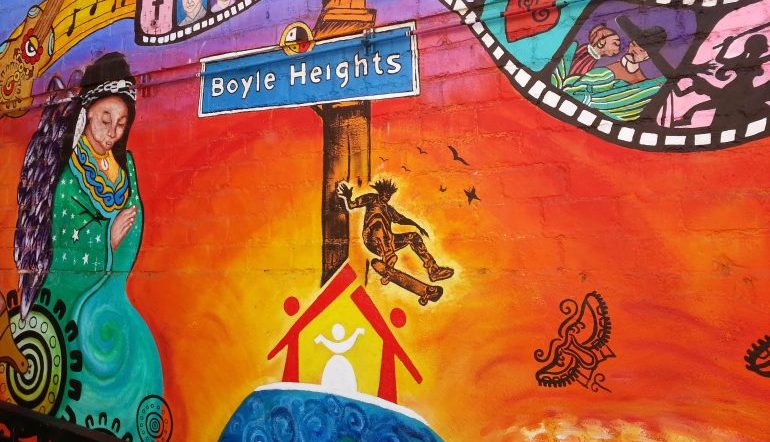

The ability to read the evolution of one’s culture is a factor in cultural legibility, too, which I think is different from simply knowing the history of one’s culture. Chicanx, for example, is something I’m constantly grappling with as a Mexican-American novelist. Not because I dislike the categorization—I think of it as a high honor—but because in many ways I feel like I haven’t earned the right to that title. It wasn’t me who put my body on the line in the Chicano Civil Rights Movement. Not me who risked expulsion, jail, and billy clubs by boycotting class at Garfield High School and sparking the East L.A. Walkouts. Not me who led or participated in the 1965 Delano Grape Strike. Or organized anti-Vietnam demonstrations across the Southwest. Or created some of the world’s most beautiful murals in Boyle Heights.

Of course, I know that history, but am I culturally legible in writing from that place? Might I, or anyone of my generation, be culturally legible in creating works that belong to the canon of a civil rights movement without sharing the experiences of those who lived and fought for Chicano civil rights? And how might writers of my generation carry the torch passed on from those particular writers whose work was born in the crucible of that struggle?

The next iterations of Chicanx literature feel like a segment of something new—not so much a reaction to Chicanx as much as a blooming of those seeds in the contemporary. And when I read the work of Analicia Sotelo or Francisco Cantú or Benjamin Garcia, I’m seeing literature that’s increasingly international, increasingly nuanced when it comes to sexuality and gender, but also increasingly in touch with the fabric of the era, which is this dark new chapter in America. If our literature reacts to anything, now, I wonder if it reacts to that darkness. The current era might drastically change the lens or entire genre through which that work might be read.

But regarding the American experiment in its current form, virtually every Latinx writer I know living in America right now (and many Latinx writers outside of the country as well) feels like they’ve got skin in this game. This might be the unifying element of a new kind of movement—this radical claiming (or re-claiming) of American in Mexican-American, Colombian-American, Cuban-American, or even Undocumented American in order to save this country from itself.

That wouldn’t be too far a departure from the roots of the Chicano civil rights movement whose goal was essentially to preserve the dignity of its people. And in that sense, I guess there is significant connective tissue, some bridge, between the past and present. It reminds me of that quote and translation from Gloria Anzaldúa’s Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza:

Caminante, no hay puentes, se hace puentes al andar/ Voyager, there are no bridges, one builds them as one walks.