Resonance, Dissonance, and the Iraq War

This year marks fifteen years since the initial US invasion of Iraq in 2003. In Rachel Kushner’s and Lisa Halliday’s newest novels, the war lurks, ever present, in the background. Kushner’s The Mars Room takes place in a women’s prison in California in the early days of the war, which backdrops the lives of incarcerated women. Halliday’s Asymmetry follows the uneven relationship between a young editorial assistant and an older writer in the early days of the war, which punctuate their romance in early-aughts New York City and puts into question their roles as writers during wartime. Both Kushner and Halliday link the violence of imperialism to the lives of American subjects during the war in their novels, documenting the dissonances and resonances between the war abroad and life at home.

In Kushner’s long-awaited The Mars Room, Romy Hall is serving out two consecutive life sentences for killing her stalker, who followed her and her son from San Francisco to Los Angeles. Kushner draws in the Iraq War to illustrate how mass incarceration disrupts the mythos of American freedom for all. Romy argues self-defense, but all the court sees is “a young woman of dubious moral character—a stripper” who killed Kurt Kennedy, “an upstanding citizen, a veteran of the Vietnam War.” Kurt’s obsession with Romy begins in the Mars Room, the strip club where she works as “Vanessa”; he likes her because she is “one hundred percent girl.” He has a vision of femininity, and she—with her long legs, “grab-able” breasts, and short dresses—fulfills it perfectly. He follows her home from the club and sees her with a little boy who he is sure could not be her son: “It didn’t fit,” he says.

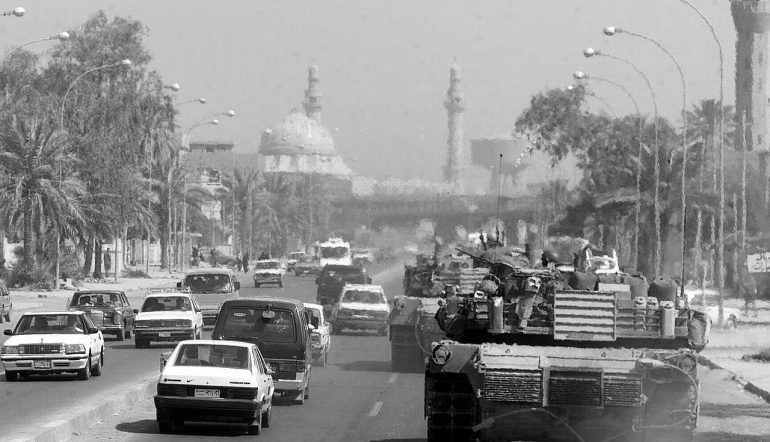

War, in America, is performed under the guise of benevolence. In Vietnam, where Kurt fought, and in Iraq, the war machine is portrayed as a protectorate of American freedom, which the United States is generously extending to innocent civilians abroad. It’s a lie, one whose logic Kushner rightly extends to mass incarceration and patriarchal violence. Prisons are justified as “correctional facilities,” a place for the rehabilitation of those deemed criminal, while the dominance of men over women has been rationalized as a product of women’s inherent weakness.

Romy makes a living identifying and performing the delusions men have about women. She knows what they like, which is also to know that they’re dangerous. Unfortunately, the things women know about men don’t protect them from their violence. This is especially true for Romy, who ends up in prison, separated from her son, with no way out. She was trapped outside by Kurt, and now inside as well. “There are American soldiers over in Iraq… protecting your freedom,” another prisoner tells Romy while they’re locked up in administrative segregation. “They can have my freedom,” she responds. “It sucks.” Mass incarceration punctures the argument of American war: whose freedom are the soldiers fighting for? Not Romy’s.

Kushner links together violence on a personal level to the state-sanctioned forms of war and incarceration. “There were stark acts of it: beating a person to death,” muses Gordon Hauser, the English teacher at Romy’s prison:

And there were more abstract forms, depriving people of jobs, safe housing, adequate schools. There were large scale acts of it, the deaths of tens of thousands of Iraqi civilians in a single year, for a specious war of lies and bungling, a war that might have no end, but according to prosecutors, the real monsters were teenagers like Button Sanchez.

Button Sanchez, one of Gordon’s students who is incarcerated, is guilty—but the point is that she’s in prison while those behind the Iraq War are not. Certain forms of violence, like war, are celebrated and justified by the state, while the individual crimes of women like Button Sanchez and Romy are punished by that same system. In connecting the different levels of American violence, Kushner draws into question the sanctity of certain forms over others.

Where The Mars Room uncovers the resonances between the American war and life in America, Asymmetry is a book about its dissonances. Composed of three parts, Asymmetry begins with the unlikely romance between Alice, a young editorial assistant living in New York, and Ezra Blazer, an older, established writer, during the beginning of the Iraq War. Their relationship is playful and loving but framed by the imbalance of power between the two—Alice wants the successful writing career that Ezra has. She wants to write about “Other people. People more interesting than I am… Muslim hot dog sellers.”

The war hangs over Alice and Ezra like a fog. They watch Bush’s televised announcement of the invasion the night before Ezra’s birthday: “‘This man is so stupid,’ said Alice, shaking her head. ‘This is going to kill me,’ said Ezra, forking the tart.” Alice’s youthful earnestness and Ezra’s lukewarm disregard are reflective of their relationship–Alice still wants so much more out life, while Ezra is near his close. But it’s also a bizarre scene, and now a familiar one, of Americans in leisure, while the president declares war on TV. Halliday furrows into the gap between the war abroad and life at home, in the hopes that mapping its vicious absurdities will provide clemency.

The novel’s second section follows Amar, an Iraqi-American man who is detained by UK immigration while on his way to visit his brother in Kurdistan. There are similarities between the two narratives, but they are slightly askew. Amar also watches the war on TV. Halliday writes dialogue with a clear-eyed mastery, and where Ezra and Alice’s banter moved with a speed and familiarity unique to lovers, conversation between Amar and an immigration agent is formally similar, but the subject is entirely different. This dissonance is purposefully jarring. Halliday’s project is to explore the “asymmetry” between the lives of Americans and Iraqis, between young women and older men, between the subjects of imperialism and the victims of war, and also between writers and the stories they tell.

The inclusion of Amar’s story in Asymmetry also reads like a corrective to the marginalization of Iraqi voices and points towards the novel’s implicit burden of guilt over the war. The trick of Asymmetry—that Amar’s story is the novel that Alice had always hoped to write—is revealed in its third section, which takes the form of a Desert Island Discs interview with Ezra. After playing his favorite Debussy, he makes an oblique reference to Alice, “a young friend of mine [who’s] written a rather surprising little novel.” Ezra’s remark is Halliday’s meta-commentary on Asymmetry’s layered narratives: “It’s a novel that on its surface would seem to have nothing to do with the author, but in fact is a kind of veiled portrait of someone determined to transcend her provenance, her privilege, her naiveté.” This is the significance of Amar’s narrative and the presence of the Iraq war—they are mechanisms for Alice and Halliday’s desire to push past their “privilege.”

When reading Asymmetry, I thought often of Ilya Kaminsky’s damning poem, “We Lived Happily During the War,” which links the comfort of American lives to the ugly costs of imperialism:

In the sixth month

of a disastrous reign in the house of moneyin the street of money in the city of money in the country of money,

our great country of money, we (forgive us)lived happily during the war.

Can you be forgiven for living happily during the war? Asymmetry traces the ugly work of the war as an attempt at forgiveness, while The Mars Room shows that absolution isn’t possible—the war touches everything.