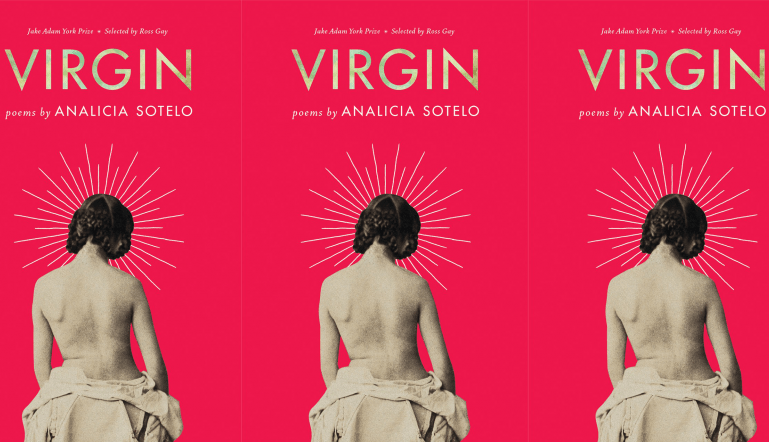

Ariadne’s Journey to Consciousness in Analicia Sotelo’s Virgin

“The book you are reading is about a girl no one believes,” says Ariadne in Analicia Sotelo’s witty, searing poetry collection, Virgin. Feminists have long attempted to “take back” feminine mythological figures and reconceptualize male-centric myths, but Virgin goes further. In a series of poems that retell the myth of Theseus and the Minotaur from Ariadne’s perspective, Sotelo not only subverts feminine stereotypes but also challenges the common wisdom of the symbolic “feminine.”

In Greek mythology, Theseus is tasked with killing the Minotaur, a monster that is half-man, half-bull and that lies at the center of the impenetrable labyrinth. Ariadne, the Minotaur’s human half sister, falls in love with Theseus and gives him a ball of thread that unravels through the labyrinth, allowing him to successfully defeat the Minotaur. Theseus and Ariadne run away together, and then he abandons her on the island of Crete without warning or explanation. Ariadne is the key to Theseus’s success and glory, and yet she is primarily remembered as a tragic example of the “spurned woman” archetype.

Several of Sotelo’s Ariadne poems explicitly seek to take back this narrative and restore Ariadne’s agency. In “Ariadne Plays the Physician,” for example, Ariadne feverishly tells the reader:

We must set this story straight.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Theseus,

you know you didn’t break me.I was the one who came to you

with a magnifying glass.

In “The Ariadne Year,” she protests, “When I sleep, / I don’t dream of Theseus,” and attempts to reverse the stereotypical gender dynamics of their relationship: “Theseus? What a joke. / A pawn, a plaything, / a custom doll.”

Sotelo doesn’t simply thwart sexist stereotypes, though—she creates a vibrating tension between Ariadne’s agency and Theseus’s toxic masculinity. In “Death Wish,” Ariadne recalls all of the women Theseus holds responsible for his suicidal ideation—his therapist, his mother, and herself. And in “Ariadne Plays the Physician,” Sotelo subverts the masculine trope of a power-mad Victorian physician by depicting Ariadne’s attempt to study Theseus’s “humours” and “monitor [his] ailments.” She fails to find answers to her long-sought questions about Theseus’s betrayal (“What is man? What is // man? What is this man doing here / with me? No bright conclusion.”), but she takes pleasure in exerting power over him just the same.

The character’s very modern sense of agency challenges the Freudian reading of Ariadne’s “feminine” power. Sotelo herself has cited the common interpretation of the myth in psychoanalytic circles, which was later referenced in Nadia Choucha’s book, Surrealism & the Occult: “Surrealism now aimed to link the conscious to the unconscious and provide an Ariadne’s thread (intuition) to lead Theseus (the conscious) through the maze of the Minotaur (the unconscious).” Broadly, feminine “insight” is the key to traversing the unconscious and facing one’s inner monster.

Sotelo’s poetry supports the Freudian idea that Theseus represents what she calls “hyper-masculinity,” while the Minotaur is a concentrated, primordial version of masculinity which, according to the Archive for Research in Archetypal Symbolism, is “destructive to … the ego when it identifies with it.” She challenges the notion, however, that Ariadne was able to help Theseus because femininity is more “primordial,” and therefore more closely linked to the unconscious, than masculinity. “The Minotaur’s Letter to Ariadne,” for example, seems to traffic in the tenderness between Ariadne and her half brother (“Like a buttercup was your heart in my hand / in the field when we were children”) but then takes a sobering turn when the Minotaur misogynistically implies that their mother was a “whore.” Further, Sotelo explicitly draws a connection between Theseus and the Minotaur in “Ariadne Discusses Theseus in Relation to the Minotaur”: “When a man tells you he’s a monster / believe him.”

Sotelo’s poems not only shift the “hero’s journey” to center on a woman but also attempt to un-gender the archetypal journey towards consciousness. According to ARAS, that journey is always “symbolically masculine,” regardless of the protagonist’s gender, but Sotelo begs to differ. In “Ariadne’s Guide to Getting a Man,” Ariadne instructs the reader to transform the feeling that “no one could love you ever” into papier-mâché monsters and then “make the monsters fall in love.” In Virgin, the monstrous Theseus—as well as Ariadne’s friends’ husbands with their “muscles, horns, and hooves”—are the embodiments of the women’s unconscious fear that no one will ever love them. Although Sotelo never provides an easy resolution to this predicament, one could argue that the existence of the poems themselves serve as a refutation. Through writing, Sotelo allows Ariadne’s stereotypically feminine concerns to make the journey from the unconscious to conscious creation.