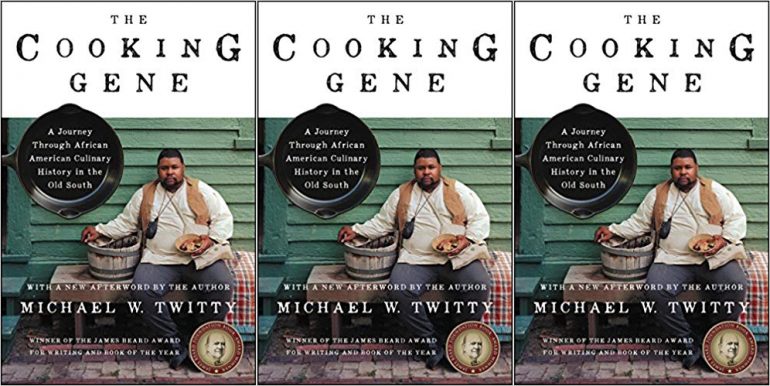

Tracing Ancestry in The Cooking Gene: A Journey Through African American Culinary History in the Old South

The beginning of The Cooking Gene: A Journey Through African American Culinary History in the Old South finds author Michael Twitty sporting a host of cultural and ethnic identities: African American, gay, Jewish. While his homosexuality is something he’s been contending with ever since he was an adolescent, and while his Judaism was a result of a choice to convert, a feeling of deep belonging to something into which he had not been born, his African American identity—though the most visible of them all—feels shaky, lacking in a steady foundation of heritage and history. For Black Americans, Twitty argues, the search for identity involves a degree of persistence and determination not fostered by most people. Even for Twitty, who was repeatedly taken to the South as a child for family reunions and memorial services, seeking out his genealogy and family history required sorting out stories both written and spoken, uncovering lies and omissions, and forcing demons awake.

As an Ashkenazi Jewish woman raised in Israel, I’ve often pondered the decision making process that goes into certain Holocaust survivors’ not to share their trauma with their children and grandchildren. While the motivation—protecting their loved ones from a past too bloody to relive, protecting themselves from reawakening demons—is clear and understandable, it always seems to me that the method misses its mark. A child growing up in the shadow of atrocities past will always sense what isn’t being spoken. Not learning the truth can lead to conjecture often bordering on the fairytale—a guesswork that could grow monstrous, worse even than the truth. When children try to imagine history, it can be even darker, more shameful, and more twisted than the real thing.

Twitty calls this “blood memory”—recollections of a past not individually lived. The genetic charge inherited through years of oppression and fear experienced by ancestors. The things we know, deep inside, without knowing we know them.

But while, for my Israeli-born friends and I, the process of unraveling the trauma of Jewish Holocaust survivors could be performed in the relative safety of a state designed around our wellbeing, for African Americans, the revelation must happen on the same dirt and within the same nation that inflicted the hurt. How were his grandparents and other relatives who lived through slavery supposed to tell young Twitty that the land in which he was born was the same one that had betrayed him? How could they reveal to him that many of them at one time were viewed as inheritable possessions rather than individuals? Property rather than people?

Still, he had to find out. Through persistent interviews with relatives, historians, and activists, he began the journey that would take him all over the country and ultimately, to Africa. DNA testing (of which he’d done plenty) could only take him so far.

While he learns, through this journey, an abundance of information about the origins of his varying ancestors (and discovers some previously lost relations), the results are, to a great extent, inconclusive and depend on additional data being gathered from other family members, as well as more data regarding the African American population at large. If anything, all this research and testing, revealing ancestors from Scandinavia, the Middle East, and many different African ethnic groups, only expands and blurs the borders of his identity. Twitty leans into the multitudinous quality of his lineage, imagining the many places and people to which he might be connected.

But accepting that the truth is more complicated and multilayered than one might have hoped requires a language through which to enter the fray. And for Twitty, the best way to communicate and explore is through cooking. Throughout his life, the kitchen was the place where truth always found Twitty. It was where he first came out to his mother. Where he first felt kinship toward Jewish tradition. And where he decided to delve as deeply as possible, willingly losing himself, into the culinary history of his ancestors. Traveling across the American South, sometimes accompanied by collaborators in what he dubs the “Southern Discomfort Tour,” Twitty visits the remains of plantations and their kitchens. Speaking to veteran culinary experts and reading historic and personal accounts, Twitty slowly uncovers not only the types of dishes and manners of preparation that were common among Black populations (both free and enslaved) in the South but also the lineage of different foods: crops like sugar, corn, yams, and black-eyed peas; dishes inspired by what enslaved Africans brought with them from their homelands; meals taught to them upon arrival. Twitty observes how each new population that arrived introduced new ways of preparing foods and new languages with which to speak of them. He also steps literally into the shoes of his forefathers: wearing the kind of clothes they would have worn, using the same—and now obsolete—tools, and taking the time, avoiding shortcuts, to do things as closely to how they would have.

In investigating the foods that his relatives would have cooked day in and day out for their masters, as well as the simpler, less nourishing foods they would have eaten themselves, Twitty studies the origin of each ingredient and dish, exploring the ways they would have traveled from different areas of Africa, through “slave seasoning” stations in the Caribbean Islands all the way to southern slave ports such as Charleston and New Orleans. He also investigates the ways in which food had enriched his family’s identity while also enslaving them. In the American South, a cultural mélange of African slaves, Creole immigrants, and slave owners of European heritage led to inspiring food composites and fascinating lingual inventions made to name these culinary creations. At the same time, major crops, such as cotton and sugar, required more and more laborers to tend to the fields, and the high value of some of them called for expert handling. The profitability of these industries served as all the justification slave owners and traders needed to deliver more and more African men and women into bondage, rating them by their skill level in one particular crop or another. These days, the source of many of these dishes, as well as the question of who is entitled to claim their ownership or invention, is still being debated. Many enslaved cooks were trained in unfamiliar culinary traditions (such as Thomas Jefferson’s cook James Hemings, who accompanied his master to Paris to study the art of French cuisine). In turn, many plantation cooks taught their traditional methods of food preparation to their white slave owners. For people born and raised in the South, in households where “Soul Food” is a staple, it may be bewildering, at the very least, to consider just how fraught and violent the trajectory of the dishes on their plates was.

By researching these foods—where they were grown, how they were cooked, and who got to enjoy them—Twitty traces his own complicated DNA, coming to terms with some of the family rifts that led to his multitudinous origins and the violent significance of his several white ancestors. For instance, he is reunited with distant relatives to whom he is connected by a white ancestor who impregnated two mulatto women. While one of the children was raised like nobility, the other was raised like a slave. The siblings barely knew each other and soon lost touch, and the related descendants only found each other through the writing of Twitty’s book.

It is difficult, when reading The Cooking Gene, to discern just how all this affects Twitty’s emotional state. He seems at once incensed and comforted, upset and accepting. More than anything, throughout the book he maintains a poetic curiosity about the complexity of it all, finding solace in conversations with people of all races along the way and in creating unique dishes that reflect his own combination of born and chosen heritage (such as hamantaschen cookies made with Southern tea cake dough).

I couldn’t get his attitude of openness and bravery out of my mind. From a young man just beginning to come to terms with the painful reality of his family lineage to a historian well-versed in the ways his ancestors were dehumanized to create the cuisine celebrated by white people in the South to this day, Twitty kept an open mind and heart to every new discovery that crossed his path, placing knowledge as his top priority. By taking his research out of the library and into the fields and the kitchen, by focusing on the minutiae involved in true plantation cooking (harvesting, chopping wood), he became an advocate for a true understanding of what enslaved cooks’ lives truly looked like and a holder of memory for the atrocity that brought his family into America.