Hearing Voices: Women Versing Life Presents Marina Tsvetaeva

Up to the age of four, as my mother testified, I told only the truth, but after that I must have come to my senses – Marina Tsvetaeva

I made an Easter quiche yesterday, and as I worked I thought about Marina Tsvetaeva, what I could tell of her that couldn’t be found in Wikipedia. As I cut the flour and butter for the crust, I thought hard. I took my rolling pin to it, and then, as so often happens with my crust, it fell apart. I pressed the dough firmly to piece it back together, and even then there were gaps where the ceramic shone through.

Like the mind, the perfect pie crust is a mystery. As I worried my fingers over the edges, I thought about how Tsvetaeva’s life is like a patchwork pie crust with too many bakers trying to mold the broken edges, make them hold.

I first read translations of Marina Tsvetaeva’s poetry (translated by Jean Valentine and Ilya Kaminsky) in last month’s issue of Poetry Magazine, but Tsvetaeva’s name— like a fish hook that lets go the trout’s mouth at the troller’s tugging— slipped from memory.

I stumbled upon Tsvetaeva’s poetry while reading Jane Hirshfield’s Women in Praise of the Sacred one evening not long after reading those Poetry translations, and this time Tsvetaeva’s name, her words, her story stayed with me. It may have been coincidence to find her again, or perhaps there was a tender point in my subconscious, a brink-memory left behind from that initial encounter. Another mystery.

The words that hooked me:

By the drawbridges

And flocks in migration,

By the telephone poles,

God’s escaping us “God (3)” (tr. by Paul Graves)

I’ve scoured my undergraduate and graduate texts for some indication that I studied Tsvetaeva. There was not a whisper of her. I took an undergraduate course on modern poetry in translation for which the syllabus included Mandelstam, Rilke, and Lorca, to name a few, but only one woman: Tsvetaeva’s contemporary, Anna Akhmatova. That semester I was interested in only Akhmatova, and in the end we skipped her work for lack of time, and I, unfortunately, failed.

As most English translations of Tsvetaeva’s work appeared after my semester of modern poetry (1994), I suppose I can’t hold a grudge. Still, I wonder how many modern poetry courses include Tsvetaeva today, a woman whose work, in her time, was considered by some to be more renowned than Akhmatova’s. In a brief Internet search, I could not find more than three modern poetry syllabi that included any poets in translation. Perhaps I should thank my old poetry prof for the good work he was attempting.

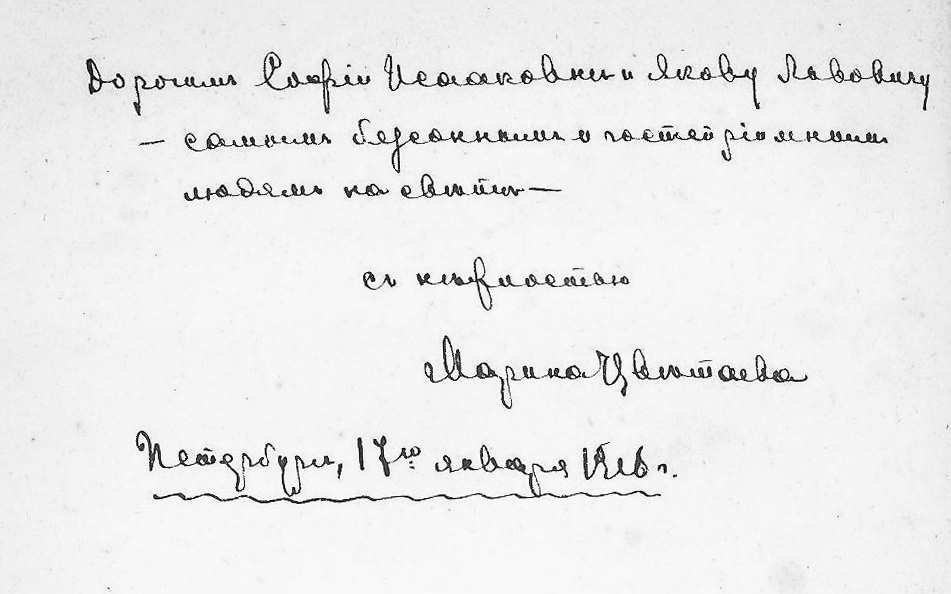

So what can I tell you about Tsvetaeva, you might be wondering. Dark Elderberry Branch: Poems of Marina Tsvetaeva, translated by Ilya Kaminsky and Jean Valentine, will be published by Alice James Books this November. This gives you seven months to get to know the cobbled together pieces of her story—if you don’t know it already— and decide for yourself what her truth is:

Was she was a traitor or a patriot to her country? Did she seek rejection and ostracism or suffer from it? Was she was mentally ill? Did she know her husband was an assassin? Who was at fault for the death of her young daughter, if anyone? Did she hang herself by choice or was she forced?

Like many of her contemporaries, so many writers even today, Tsvetaeva is an enigma whose voice and life were censored or silenced by her government.

You may find as I did that, like that quiche crust, the missing morsels, the imperfect seams, while frustrating and ugly, are unimportant when the end result— the meal, the poetry— is so delicious.