Isaac Babel’s Powerful Humor

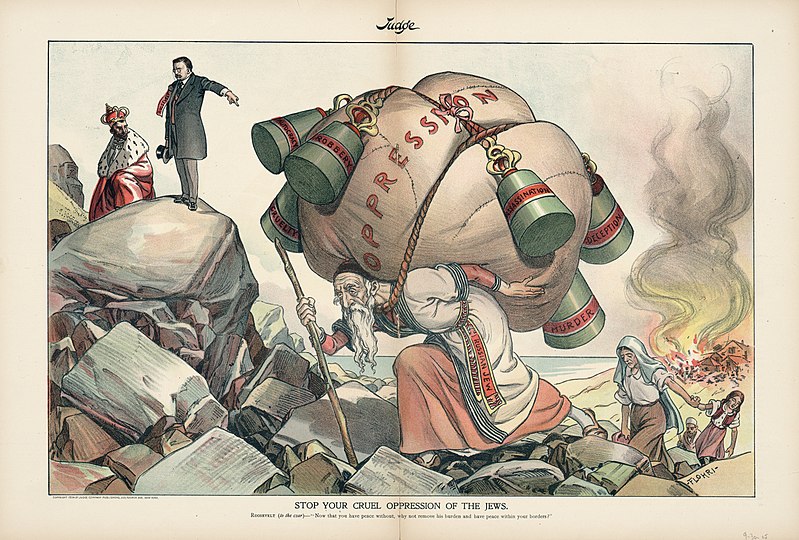

Isaac Babel would witness pogroms in his youth, live through times of disdain for Jews and intellectuals—of which he was both—and die at the hands of Stalin’s secret police. Nonetheless, this master of the short story accomplished much. Babel’s intricately styled literary voice tangos with humor in its many forms, from subtle irony to outrageous characters and clever dialogue to jocular plot twists; his stories were, as a result, guaranteed popularity and an immortal place in literature despite their being banned in the Soviet Union from his death in 1940 to 1954, and censored until Glasnost. Now, with antisemitism on the rise worldwide, reading Babel reinforces the power of wit when challenging hatred.

Babel’s stories came alive for me in a synagogue auditorium, when parents gathered Sunday mornings for reading discussions while our children studied Hebrew. Reading The Complete Works of Isaac Babel, a comprehensive collection translated by Peter Constantine and published in 2002, Babel the entertainer ensured those mornings included laughter, and Babel the realist gave us plenty of fodder for conversation. We were initially drawn to the stories in our aim of broadening our understanding of the persecution that drove our ancestors to the United States from their shtetl villages. Later, we debated the many narrative voices that emerged, wondering which—if any—expressed Babel’s own views.

We began with “Old Shloyme,” Babel’s first published story (from 1913), written soon after the author was denied entry to the University of Odessa due to restrictions on Jews. In it, Babel, who wrote in Russian and French while also being fluent in Hebrew and Yiddish, delves into the inflammatory subject of officially sanctioned antisemitism—Jewish people being forced to renounce their religion—in the years leading up to the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917. Cared for by his son and daughter-in-law who barely speak to him, for Shloyme “warming his old broken bones and eating a nice, fat, juicy piece of meat were the purest bliss.” The old man seems to have lost the ability to comprehend life. Everything changes, however, when his son announces that they are to be evicted from their home. Shloyme grows animated, notices his grandchildren no longer attend school, and asks questions. He soon intuits that his son is about to leave his people for a new God. With sudden reverence for the “greasy Torah of his forefathers,” Shloyme, who hasn’t prayed in years, refuses to join his son.

Babel wraps the story’s bleakness in droll humor, embellishing the eighty-six-year-old Shloyme with watery eyes and a “small, dirty, wrinkled face.” He is a man whose only fear is that his grandson “might catch on that he had hidden a dried-up piece of honey cake under his pillow.” Shloyme has been forgotten in “the way you forget an unnecessary thing that doesn’t jump out and grab you.” Such description cleverly sets up his unexpected defiance. Shloyme musters all his remaining strength to contemplate the impossibility of “leaving one’s God completely and forever, the God of an oppressed and suffering people.” Before Shloyme hangs himself, he declares that “there is a God, God will take him in!”

Our synagogue group was intrigued by how this nearly forgotten, listless old man could rise up in a few short pages and eloquently defend a God he had largely ignored. That Babel rendered Shloyme such an unlikely martyr is largely why the story succeeds—the ironic twist gives it punch. We did question, though, why Babel created such a pitiful character to defend Judaism, and wondered about Babel’s allegiance to his religion.

Babel appeared far more enamored with the unconventional Jews who emerged during the social upheavals following the Revolution—the ones who broke out of the shtetl culture and became gangsters and fighters. The pieces in his Odessa Stories collection, originally published as Odesskiye rasskazy in 1931, delve into the colorful Jewish underworld; these works were written during the same period as his Red Cavalry (1926) stories, which are filled with wild horse-riding Cossacks. As he gained greater recognition, these stories’ flamboyant characters gave the author wider latitude to evolve his humor and aim his mockery at real-life events and people.

Babel kept notebooks during his time as a war correspondent in the first Soviet campaign, which was against Poland. The sharp sense of reality that permeates the Red Cavalry stories was partially due to his mixing Soviet commanders from his notebooks with fictional characters. After these pieces were published, as Konarmiya, they were translated into English, French, Italian, Spanish, and German, turning Babel into an international literary figure and one of the Soviet Union’s foremost writers. “Was he a Soviet writer, a Russian writer, or a Jewish writer?” his daughter Nathalie Babel asks in her preface to The Complete Works of Isaac Babel. His work defies categorization, she concludes, explaining that “the juxtaposition of compatibles and incompatibles keeps Babel’s prose in a state of constant tension and gives it its unique character.” As his later stories show, this juxtaposition also gave him the ability to tackle horrific events with comic flourish.

My grandmother had come to America as a young girl from Odessa around the same time that Babel’s career began in that Ukrainian port city with its large (though dwindling) Jewish population. She spoke only of violent riots against Jews, hunger, and fear. Babel had to create the audacious Benya Krik in his Odessa stories to capture readers and, early on, to spoof Czarist Russia.

In the 1921 story “The King,” Krik, “a King of gangsters,” is informed by a young man of an imminent police raid on him as he prepares to host a Jewish wedding feast. Krik sends him off with a thanks, but has several of his friends follow the man. Meanwhile, the lavish ceremony—with Krik’s forty-year-old sister as bride—unfolds with gift giving, shamuses (whirling dancers who jumped onto tables and sang out), and “a bass fiddle clashing with a violin.” The King appears nonplused by the threat of a raid and tells his Papa to “eat and drink and don’t let these foolish things worry you” when the odor of burning spreads over the courtyard. The young man, however, returns at the end of the feast:

‘King!’ he said. ‘I have a couple of words I need to tell you!’

‘Well, speak!’ the King answered. ‘You always got a couple words up your sleeve!’

‘King!’ the young man said with a snigger. ‘It’s so funny—the police station’s burning like a candle!’

Although published after the Revolution, “The King” is set in Czarist Russia. The police plan their raid on Krik because, as the chief tells his station, “when you have His Majesty the Czar, you can’t have a King too.” Krik—as antihero—outwits the Czar’s men by burning down the police station before they can launch a raid. The juxtaposition of Krik as gangster King of the poor Moldavanka ghetto with the Czar as ruler of an autocratic regime provides robust parody.

Although Babel and many other Jews supported the Revolution, the overthrow of the Czar did little to stifle antisemitism. The new Soviet Union took efforts to scale back all organized religion and promote atheism. One of the narrators of the Red Calvary stories is Kiril Lyutov, a young journalist struggling to fit in with the Cossacks; Lyutov was also the identity that Babel took as a correspondent to survive among the fiercely anti-Semitic Cossacks.

In “The Church in Novograd,” Lyutov accidently stumbles into a church cellar and is hauled out by Cossacks carrying candles. He absurdly assumes these intransigent Communist fighters have come to the church to pray. They are there to ransack the church for hidden valuables. In the church, Lytov describes how “Virgin Marys, covered with precious stones, watch us with their rosy, mouselike eyes, the flames flicker in our fingers, and rectangular shadows twist over the statues of Saint Peter, Saint Francis, Saint Vincent, and over their crimson cheeks and curly, carmine-painted beards.” The Cossacks find gold coins, banknotes, and “Parisian jewelers’ cases filled with emerald rings.” As they count the money in the military commissar’s room, Lyutov is shaken: “‘I have to get away from here,’ I said to myself, ‘away from these winking Madonnas conned by soldiers.’”

The story applies considerable tension to both the Cossacks and the Catholic Church. When Lyutov, at the start of the story, delivers a report to a military commissar staying in the home of a Catholic priest who had fled, he is given sponge cake by the Jesuit’s housekeeper: “Her sponge cakes had the aroma of crucifixion. Within them was the sap of slyness and the fragrant frenzy of the Vatican.” By jabbing both the Cossacks and the Church with his cynical wit, Babel sides with neither and the largely true story could reach many readers.

As he continued riding with the Cossacks, Babel took no effort in his writing to dignify the real-life generals who would later become officials of the Soviet Union; rather, they are laughable. In “Czesniki,” Semyon Budyonny, the actual commander of the cavalry, is asked to give his men a speech before battle. “Budyonny shuddered, and said in a quiet voice: ‘Men! Our situation…well, it’s…bad. A bit more liveliness, men!’” A regular enlistee steps up. “‘To Warsaw!’ the Cossack in the bast sandals and the bowler hat yelled, his eyes wild, and he slashed the air with his saber.” The overhasty attack on Czesniki ultimately leads to defeat. The Soviets wanted to stifle awareness of this disastrous campaign to bring Communism to the world; Babel ensured readers worldwide would know of it.

Despite his success, Babel grew increasingly conflicted, wanting to believe the Revolution was good for the lowest social stratum, but intellectually realizing that was not true. Was he a Jew or a Revolutionary? A conundrum, as he could not fully embrace both since the Soviet Union would eventually ban the Jewish Sabbath. His internal discord plays out in the story “Gedali,” as the narrator wanders through the streets of Zhitomir, a Ukrainian town with a large synagogue, looking for “the timid star”—the Star of David—and finds the ruins of a bazaar. Only Gedali, his junk shop hidden among tightly shut market stalls, remains to strike up a conversation: “‘So let’s say we say “yes” to the Revolution. But does that mean that we’re supposed to say “no” to the Sabbath?’ Gedali begins, enmeshing me in the silken cords of his smoky eyes. ‘Yes to the Revolution! Yes!’” As their dialogue continues, Gedali proclaims that “good men do not kill.” Therefore, “the Revolution is done by bad men.” The narrator retorts that “the Revolution cannot not kill”; Gedali insists that “I want the International (an organization founded in Moscow to promote Communism worldwide) of good people, I want every soul to be accounted for and given first-class rations.” The story ends on a poignant note: “The Sabbath begins. Gedali, the founder of an unattainable International, went to the synagogue to pray.”

Revisiting Babel’s stories nearly two decades after my initial reading, I have greater appreciation for his accomplishment. The enemy did not seem to be coming from within when I first encountered The Complete Works not long after 9/11. Now, attacks on synagogues and other hate crimes occur frequently within our borders. Babel lived his short life always in immediate peril, and examining how effectively he wielded humor against hate—from state-sanctioned antisemitism to Stalin’s generals—is a tribute to his mastery of words. Babel’s powerful stories outlived his censors. Nonetheless, Babel was an enigma. Many critics over the years have speculated on the riddle of Babel’s personal convictions. As Nathalie writes in her preface, “the critical literature on Babel’s works fills bookcases, compared to the mere half shelf of his own writings.” The eternal riddle over what the author believed may have been Babel’s last laugh.