Lost Generations

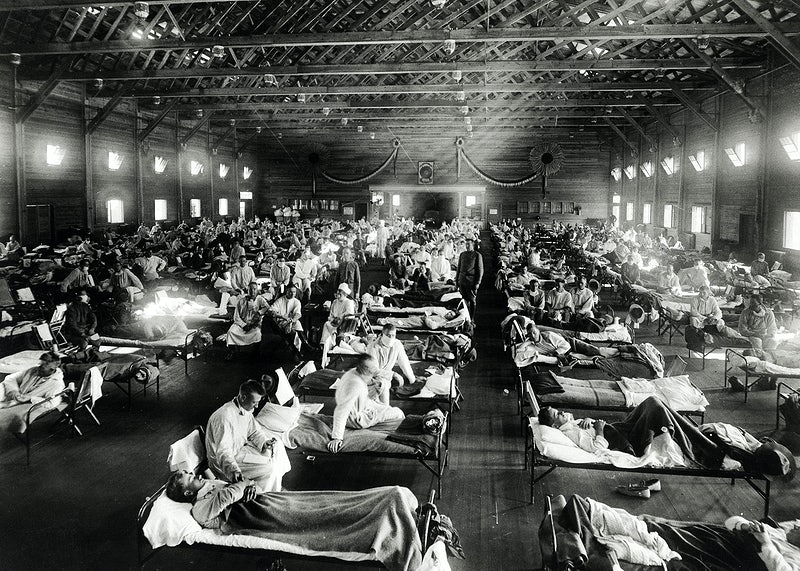

In her 2017 study of the Spanish Flu, Pale Rider, Laura Spinney suggests that the popular notion of the lost generation as it applies to those who served, died, and came of age during the First World War has been misapplied. We should think instead, she contends, of the millions of people we lost during the flu pandemic between 1918 and 1919. In those two years, the virus burned around the world in the wake of global conflict, killing an estimated fifty million people. And while the Spanish Flu cut across class, age, and gender barriers, it disproportionately killed young adults in the prime of life, further decimating an entire generation, which had already lost so many during the Great War. Surprisingly, however, the memory of this global catastrophe seems to be largely absent in the cultural productions of the first half of the twentieth century.

Despite the fact that the Spanish Flu radically reshaped global demographics, influenced the outcome of the First World War, affected statecraft and post-war policy, and laid waste to whole communities, very little literature deals with the disease directly, especially when compared to concurrent literature of the First World War. The reasons for this collective forgetting are many, complex, and difficult to identify. The scale of death was perhaps impossible to comprehend or represent. The numbers of the estimated death toll even now send the mind reeling. The scourge was invisible—attempts to blame it on immigrant communities or neighboring countries speak to a cultural need to lay the blame somewhere, a need mirrored today in the rhetoric that frames COVID-19 as the “Chinese Virus.” Relatively nascent germ theory and the fact that viruses were barely understood in 1918 also made the flu a difficult concept to grasp, especially among non-scientific communities. Perhaps the greatest difficulty, in an age where God was dead and man had killed him, was understanding the power of something that was neither divine nor human in origin to change completely the course of history. For all these reasons and more, we are only now just getting around to processing this trauma, as the specter of the Spanish Flu makes appearances in shows like Downton Abbey and is increasingly the dramatic backdrop for new works of historical fiction.

The world’s inability to represent and articulate the effect of the global pandemic in the wake of 1918 has everything to do with how we process inexplicable catastrophe as a species. Catherine Malabou, in her study of psychological responses to physical and cerebral, as well as sociopolitical, traumas, argues that, in the wake of a traumatic event, a “new” subjectivity is born. As such, the event itself can never be fully understood or comprehended, because it always happened to a departed subject. Malabou names the survivors of these types of trauma the New Wounded. This mode of being, characterized by indifference, ambivalence, and detachment, “appears in the aftermath of wars, terrorist attacks, sexual abuse, and all types of oppression or slavery. Today’s violence consists in cutting the subject away from all its accumulated memories.” One reason for our collective forgetting of the 1918 pandemic is that we were culturally unable to process the extreme violence of that inexplicable catastrophe. Even though it happened, we cannot fathom it as having happened to us, as being part of our own history.

As a result, very few authors in the early twentieth century grappled meaningfully with the Spanish Flu. Willa Cather, Katherine Anne Porter, and Thomas Wolfe, however, all dealt with the disease in some way in their writing. What their stories describe—and more importantly fail to describe—about the disease speaks to the way in which the Spanish Flu constitutes a traumatic “blockage,” an opaque event through which it is nearly impossible to look back to try to understand how things unfolded, how we felt, how we survived. Each of these stories in their individual responses to the trauma of a global pandemic thus offers us some insight into how community illness can obscure collective memory, how difficult it can be to even articulate what happened, and, perhaps most importantly, how this “new wounding” takes the form of an insistence at looking forward, whatever the cost, to a post-flu world.

Porter’s “Pale Horse, Pale Rider” (1939) is perhaps the best-known example of flu fiction. This story is remarkable in its bold attempt to represent the experience of contracting, suffering from, and finally surviving the Spanish Flu. It is a fragmentary narrative that embraces formal and aesthetic experimentation in order to show how the illness could upend perceptions of reality. The flow of events is filtered through Miranda Lambert’s stream of consciousness as she grapples with sickness, moves in and out of fever dreams and consciousness, and becomes increasingly delirious as her case worsens. When Miranda eventually begins to recover, both her body and the world into which she has awoken feel completely unfamiliar. “Sitting in a long chair, near a window,” writes Porter, “it was in itself a melancholy wonder to see the colorless sunlight slanting on the snow, under a sky drained of its blue.”

In the wake of the influenza, recovered patients experienced a myriad of complex after-effects, including depression, difficulty discerning colors, and certain cognitive impairments. Demonstrating these same complications, Miranda looks in the mirror and wonders “Can this be my face. . . . Are these my own hands?” Looking around her, she asks herself, “Is it possible I can ever accustom myself to this place?” She sees the world “with the covertly hostile eyes of an alien who does not like the country in which he finds himself, does not understand the language nor wish to learn it, does not mean to live there and yet is helpless, unable to leave it at his will.” Porter’s depiction of the Spanish Flu’s effect on people who survived is one of the more lucid examinations of the legacy of the 1918 pandemic. And yet, Miranda’s overwhelming sensation, when she returns to health, is anything but lucid. She feels displacement and strangeness as if she does not belong in life, and as if life is unfamiliar to her.

If, as Malabou suggests, survivors of such trauma display “permanent or temporary behaviors of indifference or disaffection,” we can see Miranda’s sense of confusion and ambivalence towards life, towards her old life, as a response to the trauma of the disease. It is not that Miranda has forgotten who she was, but rather that she no longer feels connected to that person, or to her old world before the flu. Miranda’s condition resonates with Malabou’s definition of a “new” subjectivity, which is completely separated from its past self. One of the New Wounded, Miranda is also one of the lost generation of the Spanish Flu: she finds that having survived, all of her old acquaintances are eager to get her to return to normal life and move on. When she recovers and opens her letters of congratulations, she reads absently, “what a victory, what triumph, what happiness to be alive.” These sentiments do not register with her, but she determines to tell them “what a pleasant surprise it was to find herself alive. For it will not do to betray the conspiracy and tamper with the courage of the living; there is nothing better than to be alive, everyone has agreed upon that.” And yet as she attempts to return to normal life she wonders at “the time and trouble the living took to be helpful to the dead. But not quite dead now, she reassured herself, one foot in either world now.” Even though Miranda has recovered, she is doomed to a sort of death in life, as the world around her spins onward and leaves her behind. This relentless forward-looking can, in and of itself, be a type of violence when it fails to account for people who cannot process the past, and don’t belong to the future.

While Porter’s depiction of the illness paints a startling picture of the lonely, gray confusion in which survivors of the flu were condemned to live, Thomas Wolfe’s Look Homeward Angel (1929) explores the phenomenon of sickness from the helpless perspective of those forced to watch a loved one die. Wolfe tells the story of Eugene Gant, who comes of age in the midst of the Spanish Flu. Returning from university amidst nation-wide school closures due to the pandemic, Eugene finds that his brother Ben has contracted the disease and become fatally ill. Drawing heavily on his own experience of having lost a brother, Wolfe explores in detail the inability of family and community members to fully grasp and process the horrors of the sickbed.

When Eugene descends from his train, bracing himself to see his brother, he looks at the station through a haze of confusion. He feels as if he had only just left for school and now the platform looks “fixed and horrible, like something in a dream. His strange and sudden return to it heightened his feeling of unreality.” This dreamlike state persists when he sees his brother for the first time and notes with horror that his body “seemed not to belong to him, it was somehow distorted and detached.” Resonant with the alienation Miranda feels in her own body when recovering from the illness, Eugene cannot reconcile the body of his brother with the body he sees that has been wracked by flu. Feeling trapped by the proximity of death, and the threat of an enemy he cannot see, Eugene moves restlessly about his childhood home while “the core of him, his Stranger, kept twisting its head about, unable to look at horror, until at length, it gazed steadfastly, as if under a dreadful hypnosis, into the eyes of death and darkness.” In this scene, the sense of strangeness felt by the patient is transposed onto the watcher. The Stranger at Eugene’s core, which recoils from the illness, is only able to look upon the flu patient in a state of dreamlike hypnosis and non-understanding. When Ben finally dies, the family has a “thrill of awful recognition, as one who remembers a forgotten and enchanted word.” The sick body that could not belong to brother Ben, the body that could only be looked upon hypnotically and without understanding, is returned to the consciousness of the family in a flash as soon as he dies and the suffering is over. With Ben’s death comes relief. Unable to see or feel his suffering and the nearness of death, when death actually comes to the boy the family is released from this hypnotic dream.

Upon Ben’s death, while Eugene no longer feels strange to himself, he demonstrates a detachment from the “unreal” memory of his brother’s passing. Despite the trauma of losing a brother, “Joy awoke in him, and exultation. They had escaped from the prison of death; they were joined to the bright engine of life again.” Eugene’s mind reels to the future, grasping and groping its way out of the nightmare of sickness. When, the morning after Ben dies, Eugene and his other brother, Luke, go to breakfast, Luke’s absentminded nicknaming of Eugene speaks to their condition. “Well, Eugenics” he asks, “what are you eating?” The appearance of this word at this moment to refer to the brother who survived the flu speaks to one of the ways in which the horrors of illness get remembered and forgotten, framing the loss of human life to pandemic as part of the teleological march of human history, and it constitutes an erasure.

Imagining the pandemic as an inevitable rung in the ladder of history is one of the ways in which Claude Wheeler engages with and survives the disease in Willa Cather’s One of Ours (1922). Claude embodies the desperate need to look towards a post-flu future, while ignoring the horrors of the present, as a means for survival. In Cather’s novel, the Spanish Flu only occupies the space of a few chapters. Bound for the war on a troop transport, Claude, fresh out of officer school, finds himself managing his soldiers in the midst of an influenza outbreak onboard the ship. Prior to enlisting, Claude worked a farm, feeling purposeless and destined for greater things. The war has given him the chance to be a part of something bigger, and he treats the flu as a necessary hardship he must face as his life marches implacably towards some meaning. As dozens of his men grow sick and die, Claude’s moments of grief and horror give way in cycles to episodes of forgetting, and then speculating about the future. When the first soldier passes away, his coffin is dropped into the sea and the affair is solemn. But the sea is unmoved and uncaring, and as Claude’s thoughts turn inward, he begins to share the sea’s indifference to the boy’s death. “Only a few hours ago” the narrator notes, “a gentle boy had been thrown into that freezing water and forgotten. Yes, already forgotten; everyone had his own miseries to think about.” As quickly as it comes, death is forgotten.

The bodies pile up, and Claude is run round the clock caring for the sick. As more and more young men die, their belongings are disposed of according to U.S. Army regulation. But in each instance, there is something leftover, as if the government had failed to fully account for the sum of a man’s life measured in the material possessions on his person. Claude is presented with the problem: “in each case there was a residue; the dead man’s toothbrushes, his razors, and the photographs he carried upon his person. There they were in five pathetic heaps; what should be done with them?” As the sea swallows these stricken men, the “residue” of their lives confounds the survivors. Claude picks out a few photographs to save, and “the others—just pitch them over, don’t you think?” The fragmentary nature of these mementos, and the ambivalent way in which they are discarded, seems to reflect the way in which the memories of the 1918 pandemic were preserved by those who lived beyond it. Unsure how to process all the death, unsure how to manage or preserve the residue of lives, much of it is “pitched over,” only small snapshots saved, with an eye towards the future and moving on. Indeed, when Claude “had an hour to himself on deck, the tingling sense of ever-widening freedom flashed up in him again.”

It is significant that this outbreak takes place aboard a ship on the Atlantic; it is a liminal space, representing the transition between Claude’s old life in America and his purpose-filled life in the theater of war. Surviving the flu epidemic aboard the ship signifies a transitory experience for him as he passes between two lives. For Claude, the grim reality of the flu becomes merely the space between before and after. As Claude looks off the ship into the inclement weather, he thinks that “years of his life were blotted out in the fog. This fog which had been at first depressing had become a shelter; a tent moving through space, hiding one from all that had been before, giving one a chance to correct one’s ideas about life and to plan the future. The past was physically shut off; that was his illusion.” Claude’s situation is obscure—fog clouds his vision, the vastness of the ocean speaks to the infinite, and all around him the bodies are piling up. Everything about this moment in Claude’s life defies finite understanding, close inspection, and analysis. Yet in this strange, horrific space, Claude begins planning for the future. If this illusion of being shut off from the past is part of the violence that separates the New Wounded from his accumulated memories, it is also accompanied by the illusion that forgetting is acceptable and necessary because there will be a better world that makes more sense on the other side of sickness. The assurance that we can put a pandemic behind us and return to a new and better way of life is perhaps the mode of forgetting that we are most in danger of in our present moment.

“When asked what was the biggest disaster of the twentieth century” writes Spinney, “almost nobody answers the Spanish flu. They’re surprised by the numbers that swirl around it. Some become thoughtful and, after a pause, recall a great-uncle who died of it, orphaned cousins lost to sight, a branch of the family that was rubbed out in 1918. . . . The Spanish flu is remembered personally, not collectively.” And yet even at the level of the individual, grappling with the reality of the flu and its immediate aftermath was almost impossible. In One of Ours, Claude can only see the epidemic on the ship as a gateway through which he must pass on the way to the future, not as a historically significant moment that will change the course of human history. When Miranda in “Pale Horse, Pale Rider” comes out of her flu-induced delirium to find out she has survived the scourge, she is completely alienated from her sense of self and her surrounding world. And when Eugene in Look Homeward, Angel is forced to confront his brother’s sickness, he is mired in a dream-like unreality until his brother dies and he can think clearly about the bright engine of life once more. These individual responses to the pandemic of 1918, which fail to process the shock and trauma of what happened, mirror the collective social responses of entire nations in the wake of the Spanish Flu. In the aftershock of the pandemic, a New Wounded post-traumatic nation was born, one in which the Spanish Flu was a dim memory that seemed to have happened to another people in another time.

A century later, these scenes of sickness that resist articulation ring hauntingly familiar. Once again, as a pandemic sweeps around the world, even as we study the disease, we struggle to grasp its emotional, social, and cultural impacts. Like our predecessors in 1918, we do not yet have the vocabulary to make sense of this collective experience. If part of Porter and Wolfe’s work was to show the impossibility of representing individual experiences in the sickbed and at the sick bedside, we certainly face the same challenges today. The huge spectrum of severity in cases of COVID-19 confounds any monolithic understanding of the experience of contracting the disease. Furthermore, the very conditions of the now-ubiquitous image of the COVID-19 patient, intubated and isolated, pose challenges to developing a meaningful way of talking about the most severe manifestations of the illness. Patients recovering from COVID-19 after being put on a ventilator report suffering from ICU psychosis. The combination of sedation, intubation, and complex medical treatments often forces patients into a bewildering delirium that, like the experience of Miranda, distorts the sick person’s sense of reality, leaving them disaffected and traumatized after their recovery, and unable to meaningfully articulate the experience to anyone else. Similarly, if Eugene feels estranged from his brother in Look Homeward, Angel, one of the most insidious effects of COVID-19 is the way in which it has separated loved ones from sick family members. A recent New York Times article describes the all-too-common “fog of worry and confusion” that beset a son who was unable to follow his father into the hospital to which he was being admitted, and from which he would not return. Not only do we feel estranged from those who contract the virus, unable to understand their experience, often loved ones are barred access to the sick person entirely. This “fog of worry and confusion” speaks to an inability to even bear witness to the suffering, complicating the grieving process and further estranging survivors from the victims.

And still, amidst incalculable loss and an inability to make sense of this pandemic, so much of the national conversation looks beyond what is happening now, grasping for that “bright engine of life” and a return to normalcy. Since the beginning of the lockdown, speculation about when we might get bars and restaurants back has seemed to occupy the same amount of media space as references to the estimated future death toll. Now, at the time of this writing, all fifty states, amidst massive political turmoil, have been at least partially reopened, further exacerbating the tension between yearning for a post-virus return to normalcy and coming to terms with a disease we cannot fully comprehend. Like Claude aboard the transport ship in One of Ours, this pandemic figures as a transitory moment that we must endure on the way to a better future. But also like Claude, if we look only to the future, we risk forgetting those we’ve lost, carelessly discarding the residue of so many lives. We cannot yet imagine what our future will look like, or how this trauma will shape—or destroy—our collective memory of these times. If we can learn anything from these limited literary attempts to come to terms with Spanish Flu as a site of profound cultural trauma, it is that our task in memorializing and remembering this moment in our history is going to be an immensely difficult one. There is no template for this, but first steps will certainly involve following the example of authors like Porter, Wolfe, and Cather, who attempted to meaningfully engage with the role of the pandemic in the lives of their characters. We must pay close attention to all of the different ways in which we are currently living, dying, and changing in this moment. Failure to do so would be to repeat the pain of living through the Spanish Flu, causing us to emerge on the other side of COVID-19 a radically changed and unfamiliar world, while unable to articulate clearly how we got here or what the cost was.

This piece was originally published on May 26, 2020.