Tradition in The Complete Stories

What’s included in a writer’s “complete works” is a curated lifetime: experience encoded in the past, sequenced toward a particular and brief vision into how their formal thinking has changed over time. What’s excluded from that specific edition of complete works is the uncertainty that something else might occur in the future—until a new edition is released, a new discovery made in a new stack of papers, arranged to manifest a different vision. Noah Warren’s second book of poetry, The Complete Stories, out today, begins with a poem he titles “Preface to the Second Edition”; the book begins in a curated absence. What’s been excluded from this edition—words that may have been included in the imagined first edition—and what’s been included here to shape a different experience of encountering these words in this specific order: it’s all impossible knowledge. We know the world of these poems has been shaped by moments of the past and prescient sentences anticipating the future, but that language does not exist on this page, in this moment.

What will be included or excluded from the third edition, the fourth, the final? The next book, the previous from the last? Warren’s collection restlessly situates itself in this continuum; these poems emphasize their own making, and the experience of reading them on the page, as process. “In a previous draft, I was able to imagine you rising / to walk around the city at the same time I felt the need to walk, / or setting down a glass of water as I picked one up,” Warren remembers in “Wall Mice.” Like the individual drafts of a poem, the figures that impel this book forward—the speaking “I” and imagined “you”—are staged as in-motion, figures for action, symbols to be dramatized, as if the sentences from his “previous draft” may externalize themselves to become the narration of real life. The language and arrangement of these drafts, including those we cannot see, continues to change; the person writing the poems follows this model:

In a previous draft, I understood myself

as a man who preferred to write

on cocktail napkins, because they’d tear if he got too invested.

In that one, I kept Father apart from my loneliness.

In the approximate “previous drafts” and through presumed future iterations, we learn this process began even before Warren conceived of these poems in this arrangement; it will continue further into his career, when the “Second Edition” seems so far away, never quite a transcription of the past.

As a character scripted for prose may seem designed with particular human qualities—notable faults, promises, earnest irony—Warren’s poetry is largely moved by the failure to identify his performing “I” as an abstraction whose characteristics, whose thinking seems circumscribed, determined. The Complete Stories, with its ostensible improvisation on the tropes of short fiction, finds itself daydreaming of prescriptive structures, those more readily christened what they are. A poem titled “Novel” breezily admits, “I surrounded you with a life, / I named you paragraph,” and here it seems easy. The poems are much smarter than this discursive dreaming, baffled at the several inconsistencies and contradictions one likely won’t reconcile. So the barefaced anxiety of these poems is made through a true ambivalence of “I”:

Look at you,

I said to you, and me—you were looking

expressionless at me.

From the poem titled “Abstract, Bio, Headshot”—the most prescriptive, easily marketed version of how the author presents the maker behind the work—the precision of lyrical thinking is not one that designates this as that; it’s one of extended possibility. Of the skeptical belief, here, that one might change after they’ve committed themselves to a record of action—“I edited my tongue / until it was clean. // No—my friends helped”—Warren corrects himself earlier, in “Scarcity Theory,” imagining the self, like a draft of a poem, as something to be distributed and revised. Friends may help with edits when they’ve listened to and read earlier iterations of the same story. Later the poem asks, “Have I improved at all,” and the answer to that question—the inability to respond with a degree of precision—is not what mediates the poem’s fear and needful embrace of process, but rather the question’s own being asked, scribbled in a notebook, recorded as a moment and changing.

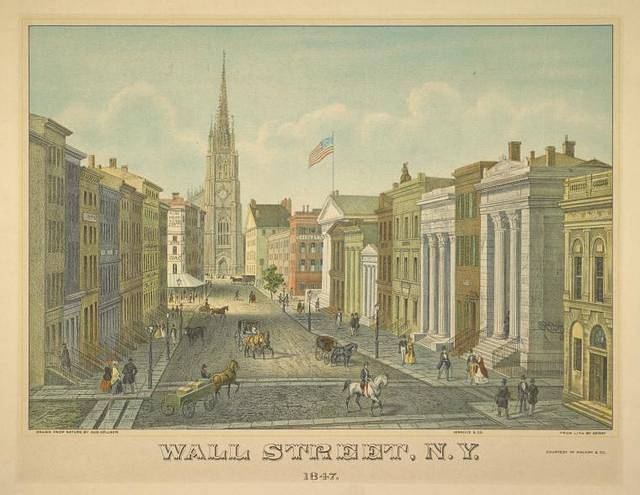

Noah Warren is the grandson of Robert Penn Warren. One of the many thunderously quiet poems in this collection, “On Value,” memorializes the poet’s relationship to his grandfather’s lasting presence in his private life, all the while trying to reconcile the latter’s legacy, including his endorsement of segregation in the early essay “The Briar Patch.” Throughout its many sections, this poem grapples with its own attempts at instruction, at corrective, as if adopting a moralizing tone risks turning the older Warren’s life into an allegory for The Complete Stories. The author of “On Value” lists the objects left behind after his grandfather’s death—a “small black-and-white TV,” “blue sewing table,” and “a birthday card from Max Ernst”—just as he examines, like a young critic, the sentences Robert Penn Warren crafted throughout his life:

My grandfather’s shortest long poem

inhabits Audubon to rediscover

the Southern landscapes, holy with grotesques,

my grandfather fled.

These lines reference Robert Penn Warren’s 1969 book Audubon: A Vision; the subtitle announces a long, tonally vatic poem in which the life of the naturalist and painter manifests a particular image of the future for the mid-century poet to observe. The grandfather Warren writes in Audubon, “The name of the story will be Time, / But you must not pronounce its name. // Tell me a story of deep delight.” These three lines are invoked, in several intonations, throughout The Complete Stories—the lyric pleasure of not saying something, of exclusion, or silence. Noah Warren notes, too, that these lines frame a question of what he names “inheritance”:

This is also his best poem,

ending in utter candor: the boy self

pleads to the poet who inherits him,

‘Tell me a story.’

What these poems inherit is a specific tradition, and in Warren’s case, one that situates itself both publicly and privately. For the formalist Robert Penn Warren of the New Critical movement, the word tradition meant something intricately timeless; here, in The Complete Stories and with Noah Warren’s emphasis on the process of making, of encountering this specific language over and over, the past inheres in the present, recontextualized for the future.

A living tradition is not history, it’s not quite the past, and it’s certainly not as rigid as what is called “the canon.” However that pattern of time is dramatized, these poems come to acknowledge the pleasure of leisurely, lovingly, sitting around to share dinner with people who narrate these stories for us, listeners in service to the language. “Most of my life I would not believe the heart of life was making pasta / with a few people, sipping maybe two glasses of wine,” Warren accepts in “The Complete Stories,” the book’s final poem. And almost as if tagliatelle would be chilling on our own desks, the stanza wakes a memory to tell its readers: “In the evenings, when I was child, / I played chess and backgammon with my father. To his credit, he never let me win.” What we do with this information—after listening to the story, closing the book—doesn’t quite matter as much as its being told in the first place, how listeners receive this language. As a process of experiencing this specific arrangement of the words, Warren’s poems foster our uncanny sense of time passing while we listen: