Guest post by Alicia Jo Rabins

A palace must have passages….a poem must have transitions.

–Samuel Johnson (via Barbara Guest)

In making poems, we cross from the known to the unknown. We destroy the drywall of the consciousness-room we’ve been living in, look at the sky beyond, and then build a new room, taking into account what we’ve seen.

A poem has transitions, as Samuel Johnson says above; writing a poem is a transition. A poem is a transition made visible.

Occasionally this process is brief and painless, but often it’s slow and messy, full of dead ends, trial and error, and, of course, no guarantee of a decent product at the end. (Not unlike dating, I might add.) Writing isn’t usually seen as a live performance art, but in this sense, perhaps it is.

Barbara Guest writes about this process beautifully in her essay “Invisible Architecture”:

Reaching out to develop the poem there are interruptions, some apparently for no reason–something else is happening, the poet has no control–the poem begins to quiver, to hesitate, to become insubstantial, the desire of poetry to elevate itself, to become stronger…The poem is fragile. It needs to reach through the armed vehicle of the poem,

to loosen the armed hand

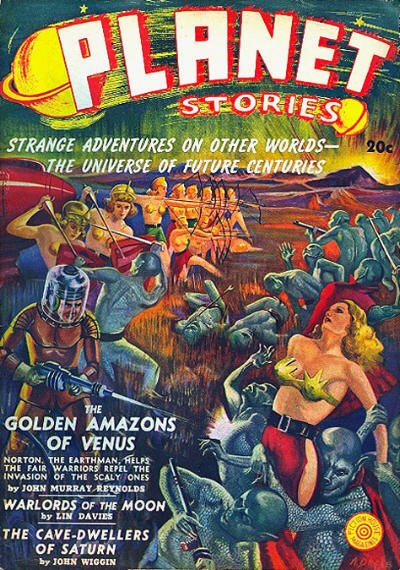

Not only do we perform the poem, but the poem performs itself through us! (Or, in the image above, through T.S. Eliot.)

Thinking of writing as performance reminds me of the interesting distinction James Arthur makes, in

his recent post, between reading dead poets (“I feel that I am sharing another person’s solitude, maybe because I know the poet wants nothing from me”) and living ones (“In some ways, I do experience writing as a team sport: I go to readings, keep up with favorite magazines, buy new books”).

I love Arthur’s idea of enacting writing community as a team sport–another performative act which is by nature imperfect, lived out in time and through bodies, more analogous to

writing a poem than to

having written one. (And the connection between writing and performance also resonates with Gabrielle Calvocoressi’s incredible, not-to-be-missed series of

Sports Desk posts currently in progress over at the Best American Poetry site.)

Some poets retain a vivid sense of live performance even on the page; Allen Ginsberg is among them. Perhaps partly because he structured his line-lengths in “Howl” according to the length of his breaths, you can feel the physicality in the poem; you can feel the poem breathing on the page. It doesn’t feel like an artifact.

Here’s a clip of a meta-interview with Ginsberg in which he instructs us on how to view the interview itself. God, I love this man:

“Don’t get hypnotized into some false universe of pure imagery.” Ginsberg is teaching us to view the film not as a “final reality,” but as an image, “with a grain of salt.”

It’s reasonably intuitive to apply this idea to live interview footage, or to a blog post, each of which are designed to inhabit and document real time in a way that poems often seem determined to transcend. But perhaps it’s a good experiment to try reading a poem, even a masterpiece, with the same “grain of salt.” After all, we live in time; any illusion of perfection, consummation, end of process, is just that–an illusion, a freezing of process. As students of poetry, though, this is hard to remember. When we read strangers’ poems, whether dead or alive, we generally encounter the “final reality” (unless it’s one of those

fantastic editions with drafts included). Reading a great poem, even an ambitious, risky one like “The Waste Land,” is not like watching a great Olympic game in real-time; it’s more like watching the highlights. Everyone knows who won, the slow parts and errors and misses have been edited out, and we marvel at the seemingly inevitable successes. And as humans encountering great art, that’s exactly as it should be.

But as poets who are in the active process of creating, it’s also crucial to know that Eliot had to do this (look at Ezra Pound’s notes in the margin!)…

…so that he could do this:

At the violet hour, when the eyes and back

Turn upward from the desk, when the human engine waits

Like a taxi throbbing waiting,

I Tiresias, though blind, throbbing between two lives,

Old man with wrinkled female breasts, can see

At the violet hour, the evening hour that strives

Homeward, and brings the sailor home from sea,

The typist home at teatime, clears her breakfast, lights

Her stove, and lays out food in tins.

Out of the window perilously spread

Her drying combinations touched by the sun’s last rays,

On the divan are piled (at night her bed)

Stockings, slippers, camisoles and stays.

I Tiresias, old man with wrinkled dugs

Perceived the scene, and foretold the rest–

I too awaited the expected guest.

–from “The Waste Land,” Part III

“Perhaps be damned” indeed!

Witnessing the real risk of process is one reason why artistic community (the workshop, the residency, the collaboration) is so important. We celebrate each other’s successes, but we also observe the fruitful disasters, the failures that inherently attend real risk-taking. Through thoughtful critique, we help each other to consider those failures without attachment–simply to compost them and harvest the richness they contain, to deepen the process, and refine the work. Yes, this is good for the poems, but helping each other also gives us courage in our own work. It enables us to return alone to our own desks and studios–to continue to walk forward into the absolute unknown and, with any luck, even to enjoy it.

Yes, our words can outlive our bodies, and this is one of poetry’s main engines–“So long as men do breathe, or eyes can see / So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.” This is beautiful, but it’s also the “final reality” that Ginsberg cautions us about trusting. Even if our poems may live on after us, we can only write when we’re alive. Time is the poet’s medium, as much as words are. Writing is live performance: real risk, real possibility.

Photo captions: T.S. Eliot photograph, http://image.guardian.co.uk/sys-images/Books/Pix/authors/2007/09/10/eliot460.jpg. T.S. Eliot manuscript, http://www.english.ucsb.edu/faculty/rraley/courses/engl165/readings/Eliot.gif.

This is Alicia’s third post for Get Behind the Plough.