John Winthrop, Don Quixote, and Donald Trump’s “Fake News”

“What you’re seeing and what you’re reading is not what’s happening.” So asserted Donald Trump to an assembled group of veterans in July of 2018 in Kansas City, Missouri. While Trump’s intention was to, once again, discredit the “fake news,” this time for criticizing his tariff policy, the remark also stands out as a surprisingly candid reveal of his facile but effective presidential strategy: if you are willing to lie to people very consistently, loudly, and without contrition over a protracted period, if you are willing to offer people a steady diet of what Kelly Anne Conway termed “alternative facts,” which brazenly belie their actual visual and critical perceptions, it is possible to convince them that, as American studies scholar Sacvan Bercovitch famously put it, “things are not really what they are in fact.”

This strategy, first identified in 1977, by researchers at Villanova University, is known as the illusory truth effect. To trace Trump’s time in office is to note how he often deployed this methodology, with increasingly dire consequences.

For instance, while it may have seemed comical, if a bit troubling, when in January of 2017 the American public looked at photos of a largely empty Washington Mall on inauguration day as Trump told them they were actually looking at the “ largest audience to ever witness” the swearing-in of a president, there was no comedy to be found by February of 2018, when the Marjory Stoneman Douglas students who had survived the mass shooting at their school were dismissed as crisis actors—or when in, February of 2020, COVID-19 was pronounced a “flu” that would soon disappear “like a miracle.” And if we were not already stunned enough by the dissonance between what we had been seeing and what we were told we were seeing, in the days following the January 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol by Trump supporters we were asked to believe that the insurrectionists who had breached the Senate Chamber and erected a gallows were “very special” people, “tourists,” and, most astonishingly, “patriots.”

And yet, far from being un-American, Trump’s deployment of the illusory truth effect is supremely so. Indeed, it is in lock step with the shady rhetorical strategies employed by Trump’s Puritan forbearer John Winthrop, who in 1630 brought one of the first groups of colonizers to the New World aboard the ship The Arbella. Like Trump, Winthrop was a crooked real estate man selling a bill of goods to his followers to make a fast buck, and, like Trump, Winthrop’s hustle depended upon his followers seeing what they actually couldn’t, and unseeing what was right in front of them.

In the same way that Trump’s Make America Great Again campaign theme was intended to impassion his followers to hearken back to a nebulous past when the United States was, allegedly, “great,” Winthrop’s Puritans perceived their journey to the New World as a reenactment of the Israelites’ migration to the promised land, which would engender the “great-ness” of that Biblical story upon them “again.” Indeed, “Nehemias Americanus” (1702), the title of Cotton Mather’s biography of John Winthrop, says it all. Mather construes Winthrop as the American version of the biblical Nehemiah, the Israelites’ leader; in the spring of 1630, all Nehemiah 2.0 had to do was sit back while history repeated itself. For both Trump and Winthrop, however, if the greatness of a remembered past was to be reinscribed in a new incarnation on new terrain, it was going to be necessary to unsee anything one encountered that might run contrary to that vision.

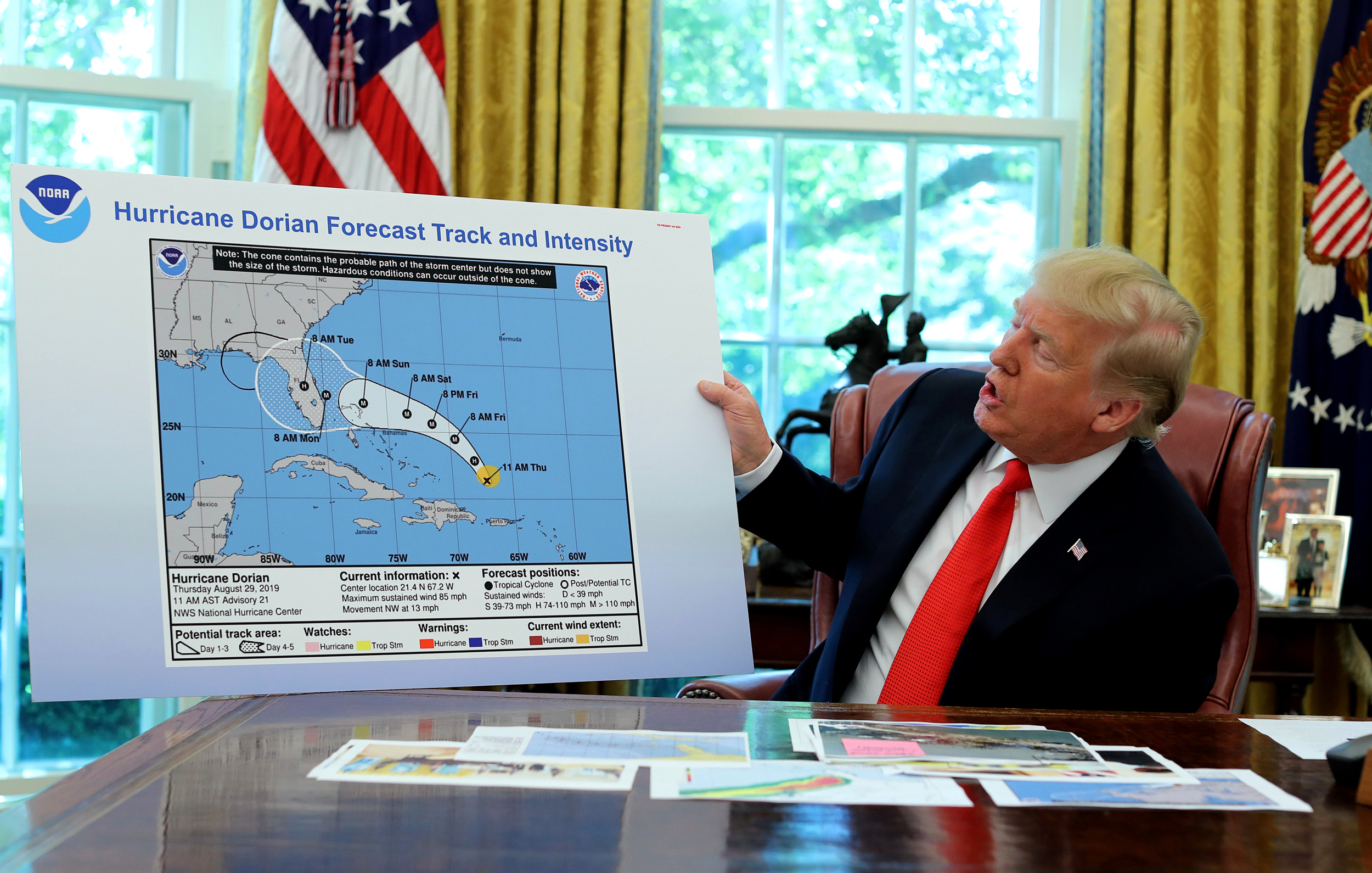

Winthrop seems to have recognized this possibility of complication. In the sermon he delivered to the Puritans while they were still mid-journey aboard The Arbella and, notably, nowhere in sight of the land they were about to call home, he asked them to envision a miraculous “city upon a hill” so exemplary that it would be a “model of christian charity.” In the service of effecting this mission, Winthrop mandated that his followers “abridge their superfluities for the supply of other’s necessities.” While Winthrop’s rhetoric on the surface appears to be a platitudinous Christian injunction benignly imploring his followers to do unto others, it is actually a sinister euphemism that deputizes the Puritans, once in the New World, to “abridge,” or edit out, anything they might encounter that conflicts with the “model” of “Christian charity” and the “model” of the “city upon a hill” they have been directed to see. In the same way that Trump, during the now infamous “Sharpiegate” incident, felt empowered to “abridge” the course of Hurricane Dorian on a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration map by using a magic marker to extend the storm’s trajectory into Alabama or, against all evidence to the contrary, to say he had never even met E. Jean Carroll, the woman who accuses him of raping her in a dressing room at Bergdorf’s, Winthrop’s Puritans got off their boat ready to “abridge” anything “superfluous” to their colonial/MAGA mission.

In urging them to see what was not there and not see what was there, both Winthrop and Trump asked their followers to act in the tradition, if not the spirit, of Miguel de Cervantes’s character Don Quixote. Indeed, for Michel Foucault in The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences (1966), Quixote is quite similar to a Puritan in as much as he is a “diligent pilgrim.” And while he does not adhere to a Winthropian model of Christian charity, he is slavishly indebted to twelfth-century chivalric romances as “written prescription[s]” of how he should perceive and exist in seventeenth-century Spain. Like the Puritans and the MAGA adherents who would follow him, Quixote’s raison d’être is “a quest for similitudes” between the knightly model to which he is devoted and his contemporary circumstances that bear no resemblance to those texts. To exist in this contradiction, Quixote is compelled, à la Kellyanne Conway’s “alternative facts,” to press “the slightest analogies . . . into service” so that “flocks, serving girls and inns” become “castles, ladies, and armies.”

In F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Crack Up (1945), the famously troubled author equates not cracking up mentally with the ability to “hold two opposed ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function.” Fitzgerald’s prose suggests there is a crack running down the psyche of the American dreamscape that ensues because of the dissonance between the “opposing ideas” of what Winthrop and Trump tell their followers they are seeing and what they actually see. To be Quixote, a Winthropian Puritan, or a MAGA adherent, then, is to eternally balance like a tightrope walker on this crack of dissonance, or risk cracking up. This, of course, is an unsustainable dynamic, for inevitably that moment will come when the crack seismically expands into an undeniable crevasse, the moment where there is no reconciling the stark reality that you are on a ventilator in an overcrowded COVID-19 ward with the euphemistic Trumpian rhetoric that the illness afflicting you is a “flu” that you should not allow to “dominate your [life].”

In the meantime, to sustain the illusion as long as possible it is necessary to caulk up the Foucauldian crack of “non-similitude” between rhetoric and reality by providing a rationale as to why “all the signs [in the world]” contradict the promise of Quixote’s and Winthrop’s and Trump’s prior texts. For Foucault, the best way to do this is to introduce the idea of “sorcery” into the mix, because the deployment of such “magic…by means of deceit” can explain away this dissonance. Indeed, with magic as an explanation, it is quite easy to swallow the Trumpian edict that what you are seeing and what you are reading isn’t happening: the flourish of a sorcerer’s wand made it so. This Foucauldian reading of magic as a means to reconcile the crack of “non-similitude” of course throws both the Puritan’s reckoning with the Salem Witch Trials and Trump’s incessant invocation of the phrase “witchhunt” into stark relief.

Some sixty years after Winthrop delivered “A Model of Christian Charity” in 1692, the Puritans of Salem, still dutifully adhering to their mandate of “abridging the superfluities,” used the witch trials largely as a means to abridge the Puritan women deemed “superfluous”—those women who were too loud, too obstreperous. Relying on spectral evidence—the belief that alleged victims were being invisibly afflicted by those they accused—the court smoothed over the Foucauldian crack of “non-similitude” between what people didn’t see happening and what they were told was in fact happening with the explanation of witchcraft. In other words, the reason you couldn’t see the witches that the white men serving as magistrates assured you were nevertheless brutalizing their victims was because of magic.

Similarly, Trump’s bandying about of the term “witch hunt” to bemoan the many investigations into him and his administration is telling, but not in the way he intended. Like the Puritans in Salem, Trump throughout his time in office sought to abridge those messy superfluities that ran counter to his MAGA model of greatness with invisible or spectral evidence. In telling his followers that things like collusion, quid pro quo, and E. Jean Carroll simply do not exist, and that things like “the wall,” particularly a wall whose construction was being paid for by the Mexican government, and his health care plan (a blank bound book handed by Kayleigh McEnany to Lesly Stahl on the set of 60 Minutes) do, Trump was unquestionably reliant on Salem-style witchery to further his agenda. And if anyone be in doubt that Trump was inadvertently but masterfully implementing Foucault’s notion of “deceitful magic” to caulk up the gap of “non-similitude” between his words and reality, look no further than South Carolina senator and Trump fanboy Lindsay Graham, who in March of this year gushingly opined that there was just “something about Trump…… some magic there” that kept Lindsay in his thrall. Who cares about the DNA sample on E. Jean Caroll’s dress when you’ve got magic on your side?

While many of the superfluous voices abridged by the Winthropian/Trump agenda over time get silenced and erased permanently, there are some, however, that take the very term meant to erase them, “superfluous” and morph it into a kind of super-fluidity that allows them to waft from the Foucauldian crack of dissonance, if only for a transitory moment, to finally set the record straight, to assert what is actually happening as opposed to what isn’t—even if afterwards they will be reabsorbed and abridged forever.

Gilles Deleuze, in The Fold: Leibniz and the Baroque (1988, published in English translation by Tom Conley in 1992) reads the authentic voice of American literature as a superfluid and “nomadic” one in that it escapes the reifying “monad” of the prior texts that attempt to encapsulate it and abridge it. Once on the road and free of the monad, this American voice “scrambles all the codes.” The word “monad” thus is free outside the monad that contains it to reconstitute and rewrite itself as an anagrammatic “nomad” or, better still, a “da[e]mon” who deconstructs a narrative bent on erasing it in favor of one that tells its true story.

In Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s nineteenth-century gothic short story “The Yellow Wallpaper,” for example, a woman in the throes of postpartum depression is confined by her doctor husband, John, to a small room, and forbidden to write in her journal, the only practice that allows her to give voice to her condition, and the only thing that affords her solace. John’s attempts to abridge his wife and her emotions as hysterical, in need of a hysterectomy, and superfluous, however, lead to her inditing a super-fluid, anagrammatic, decidedly anti-mimetic, and “daemonic” true tale of her horrific incarceration on the peeling yellow wallpaper of her prison. Likewise, in Stephen King’s terrifying novel Misery (1987), a clear homage to “The Yellow Wallpaper,” the character Paul Sheldon, a writer who has made his fortune on a bodice-ripper series about a nineteenth-century Gothic heroine named Misery, seeks to abridge or kill her off in a final installment so that he can get to work on a “real” book that will earn him fame as a serious writer, only to find that his character and her number one fan, Annie Wilkes, defy their status as superfluous and demonically take him on a surreal, horrific, and nomadic journey that sees him imprisoned, drugged and hobbled until he acquiesces to penning the resurrection of Misery. And it is only when Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita nomadically escapes her captor and rapist Humbert Humbert on the backroads of the United States that that “ little deadly demon,” as Humbert affectionately refers to her, super- fluidly “scrambles all the codes” of Nabokov’s and Humbert’s monadic and manipulative narrative. Calling BS on these two white men who seek, Winthrop style, to abridge the “superfluous” details of Humbert’s pedophilia, obscuring it in an effloresence of euphemistic prose, Lolita wafts, albeit briefly (she is killed off at the end of the novel) from the crack of non-similitude, and speaks the truth with blood-chilling clarity, telling anybody reading Nabokov’s text who’ll listen that what they think they’re holding in their hands, the putative greatest love story of the 20th century, is really just the sordid story of a “dirty, dirty old man.”

Ultimately, all these brave and nomadic daemons owe their liberation, however fleeting, from the Winthropian abyss of abridgment to she who penned their manifesto back in 1692 Salem: Abigail Williams. This colonial-era Lolita, branded a witch, dared to defy her older married lover, John Proctor—deemed the putative hero of the Salem witch trials (at least according to white man Arthur Miller, in The Crucible (1953)) when he asserted in good Winthropian style that the sex that they had definitely had out in his barn never actually happened. Refusing to be abridged as superfluous, Abigail instead scrambled all the codes of the Winthropian text of abridgement by telling her erstwhile Puritan boyfriend exactly what had actually happened in that barn. “Put it out of mind,” Proctor tells her, “We never touched.” “Aye, but we did,” rejoins Abigail. And with that, she gets ready to shimmy super-fluidily out of the abyss.