“I’m considering and reconsidering ideas of storytelling and history within a family”: An Interview with Emma Hine

Lately, I’ve had sisters on the brain. The ubiquitousness of the Kardashian-Jenners seems involuntarily foisted onto my feeds and screens. I just read the excellent Sisters, by Daisy Johnson (2020), and revisited my favorite first paragraph of any novel ever, Shirley Jackson’s We Have Always Lived in the Castle (1962). I devoured Lauren Groff’s short story “Dogs Go Wolf.” While revising Starflower, my forthcoming picture book biography of Edna St. Vincent Millay, I immersed myself in the childhood life of the poet and her very compelling sisters—working with a co-writer who, fittingly, has six sisters.

So it felt like “book fate” when I began reading Emma Hine’s debut collection of poetry, a book focused on three sisters that behaves like a constellation surrounded by an ever-blackening sky. The reader enters a world of grief and imagination, of fear and loss. The girls’ mother has a brain tumor, and a neighbor devastated by the death of a child responds with her own suicide: “she is still / in the lake, in her nightgown / her hands like cold flowers at her wrists.” To cope, the oldest sister tells stories, attempting to transform reality—maybe their mother isn’t gone, but a selkie venturing to the shore: “I told my sisters our mother was born / in the ocean. / What was the harm?”

Entering Stay Safe is like being lured into a fairy tale you think you’ve read before, but discover is intensely new. There is both danger and wonder in the myth-making (which echoes the work of Brigit Pegeen Kelly). In “Distortion for Afterward,” the proverbial Boy Next Door hangs himself from a tree in a scene both haunting and revelatory: “The leaves tilted purple above him, the earth a sick green, as if with his sudden rupture / came a broader, more permanent shift: / physics resettling from the shock / into wrong answers.” In “Flight Path,” when the sisters insist they have found a dead body on the shore, they claim the center of this unsettling story: “This is not about the man who washed ashore. / It’s about the girls who found them.” As they place clamshells over the corpse’s mouth and dig a moat around his deadness, even the exoskeletons aren’t cast as passive witnesses, but an enthralled audience: “All night little shells gasped up from the ground.”

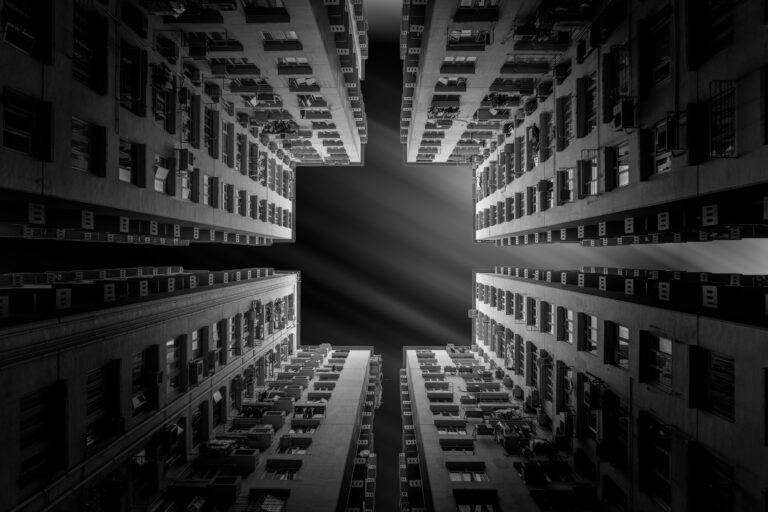

Stay Safe is designed to unsteady you: one moment you’re grounded on earth, lulled by oceanic words like sargassum, and then you’re spun into outer space with a multi-page sci-fi prose poem that tethers space travel to an excavation of family. “Echo Hotel” marks a thrilling narrative and setting shift in the collection, employing a very powerful use of the second person. The reader becomes an invisible co-pilot to the speaker blasting through her memories in a “field of / crumbling asteroids, the nebulas clustered like moths along the / galaxy’s bright spine.”

Hine’s poems burn you with their tragic luster, muscularity of language, brutally-beautiful images, and emotional heft. Despite stirring tones of loneliness and fear, however, Stay Safe evokes a flaring tension with how much light seeps into these poems. There are many moons, and there is fire, eyeshine, spidershine LED lights, headlights, glow-in-the-dark stars, and lit jellyfish. The glow is figurative as well, as if through a sister’s imagination, fictions, and revisions, a bright escape hatch is created that could almost begin an optimism. As if brightness is something you sometimes can’t help but submit to. As a starlit sister admits from the solo pod of her spacecraft: “And that little button of hope springs up in / your sternum no matter how many times it’s been pressed.”

JM Farkas: Your book centers on (and is dedicated to your) sisters. I’m curious about your literary history with sisters. One of my favorite sister poems is Brenda Shaughnessy’s “I Wish I Had More Sisters.” Which piece of “sister lit” influenced you?

Emma Hine: Two of my greatest touchstones—in general, and throughout the writing of Stay Safe—are Marilynne Robinson’s Housekeeping and Penelope Fitzgerald’s Offshore, both slight and lyrical novels about two sisters finding their way through a complicated familial dynamic alongside a body of water they fear and mythicize and can’t really separate their own identities from. Until I put it that way, I actually hadn’t realized just how much Stay Safe (and my current project, which is also about sisters) is in conversation with these two novels. For a long time, the epigraph for this book was actually from Housekeeping, after the train dives into the lake and nothing is recovered except for a cabbage, a suitcase, and a seat cushion: “No relics but three, and one of them perishable.” While this line in context isn’t about sisters, I find it incredibly potent out-of-context: sisters as the most current remnants of an earlier time, and in danger of being lost.

As far as poems go, Aracelis Girmay’s “The Woodlice” is one I return to often, and I’ve learned from how she balances sibling relationships to threat and history, as well as from her narrative approach and language. I’ve also learned a lot about exploring family relationships from Ada Limón, especially through “The Great Blue Heron of Dunbar Road” and “American Pharoah”; I love how she takes an emotionally complex dynamic and strings it alongside a charged and changing observation of an animal. Another poet I want to mention is Alberto Ríos; while he’s not writing about sisters, his recursive look at his own family’s narratives has been very important to how I think and write about my own.

JF: Stay Safe also conjures dark and emotionally resonant fairytale and mythology vibes. The title pulses with the underlying directive in all fairytales. I immediately thought of Brigit Pegeen Kelly’s “Song” when I read “Distortion for Afterward,” and then I was surprised (in a great way) when you referenced Kelly before your astounding poem “Selkie.”

EH: I’m so excited and honored that you thought of Brigit Pegeen Kelly while reading this! I came across her work relatively late, but she was definitely my most formative poetic influence during the last two years I spent writing this book. I first encountered “Song” at the office—I worked at the Academy of American Poets at the time—on the day Kelly died, looking for a line of her work to include in a brief memorial. I was completely floored. I read all three of her books quickly and then many times over; I was finally able to re-enter poems I’d given up on long before. It’s a strange experience to only discover someone vitally important to you through the news of their death. Kelly’s poems exist so specifically in their own mythologies; they feel like they should be ancient, while also perpetually contemporary in their emotional nuance.

JF: Families have their own mythologies, too. And poems seem close cousins to spells. Are you paying homage to fairytales or perhaps purposefully refracting this formative storytelling genre?

EH: Throughout Stay Safe, I’m considering and reconsidering ideas of storytelling and history within a family—what we tell each other, what is revised, what is lost or intentionally forgotten—and I gesture to fairytales through both subject matter and craft in part to help emphasize this. I think Kelly really gave me permission to lean into narrative. Entering one of her poems is like entering a house in a dream, or maybe an especially architectural garden; you know there’s a story happening in it, and you’ll be led past the gnarled pear trees and the sculptures until you find it. Before I read her work, the sequence “Flight Path,” for instance, was a pretty bland lyric essay about going to the beach with my sisters and thinking about my great-grandfather—but poems like “Song” really let me explore the extent to which I could push a fable alongside a family truth.

JF: Water and the ocean are prominent in your work, and Stay Safe is such a sensory reading experience I tasted salt while reading your poems. How does water function in your life, and the life of your book?

EH: I grew up going to the beach for a few days every summer with my family—we always went to Port Aransas, a small coastal community on one of Texas’s barrier islands, and stayed at the same raggedy hotel right on the water. This was a small percentage of my childhood, time-wise, but it loomed huge for my sisters and me. Some of my most potent memories are scuffing my feet in the surf to keep from stepping on stingrays, playing in the waves, and hoping that whatever tangled around my ankle was sargassum and not a man-o-war. There’s something wonderfully terrifying about water to me, in almost exactly the same way outer space is wonderfully terrifying: the way it looks like a flat expanse but can be entered, the cold depth, the possibility for real violence and real beauty in what exists there. I mean, sharks! Fish that glow in the dark! Wrecked ships!

JF: Speaking of outer space, after you ground the reader in the earthly world, there is a thrilling shift with “Echo Hotel,” a sci-fi prose poem, spanning seven pages and a full book section. How did this poem come to be?

EH: Science fiction is honestly one of my first loves; I grew up watching Star Trek (particularly The Next Generation and Voyager), and my sense of narrative is really rooted in these basic ideas of space travel. I never thought that this lifelong obsession belonged in literature, though, until I read Tracy K. Smith’s Life on Mars and, later, Adrian Matejka’s Map to the Stars—both of which made me feel like exploring science fiction through poetry was possible in ways I hadn’t considered. Initially, the new freedom these books gave me was just the genesis for poems like “Red Planet” and “Long View,” which consider space but don’t fully commit to the genre. “Echo Hotel” was the last poem I wrote for Stay Safe; by that point, I’d actually submitted this manuscript, under a different title, for over a year, and I was starting to feel a little despairing about the project as a whole. I decided I needed to write something that didn’t belong in my manuscript at all, something wholly different. So I woke up early one morning and re-read Bianca Stone’s The Möbius Strip Club of Grief, since her relationship to language and imagination often helps me write when I’m feeling stuck. And then I just sat down and started writing this prose sequence.

I’ve never had a poem happen in this way before, but over the next two or three weeks, I dreamed and breathed in this world. When I finished, I was hesitant to include it in Stay Safe, because it felt so strange and other. I gave it a title I’d actually been considering for the full collection—my initials in the radio alphabet, as well as a gesture toward a starship—to tie it in, and once I’d rearranged the poems to lead up to and include it, the whole book suddenly felt right to me. Sarabande was the first place I submitted the manuscript to with this poem included.

JF: The word on the street is that you’re now writing a novel. Are you swapping genres or do you plan to write simultaneously in many forms? Many who “go prose” never seem to come back.

EH: I absolutely want and intend to come back! I turned to prose initially to reinvigorate how I thought about writing and to reduce the pressure from my manuscript submission anxiety. Over the course of many months, I realized that what I was calling “my weird fiction project” was actually becoming a novel-in-progress. It’s also about sisters, about storytelling, about family history—I think I wasn’t finished exploring these ideas, so they’ve wrestled their way into a very different form. My hope is to build a writing life, long-term, around multiple genres that strengthen and inform one another. Recently, I’ve finally started thinking toward poems again, hopefully with enough distance that my newer poetry will be its own strange animal.