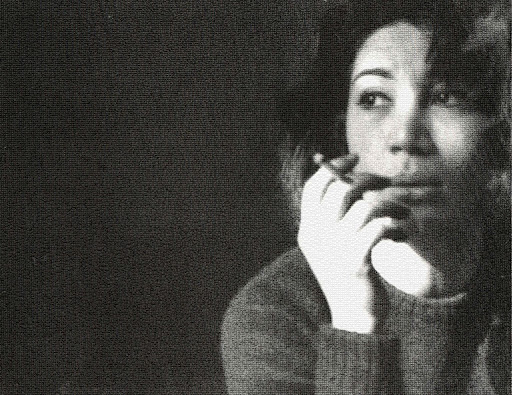

The Legacy of Forugh Farrokhzad

Two of the Iranian poet and filmmaker Forugh Farrokhzad’s most enduring works—the 1956 poem “Sin” and the 1962 experimental short film The House is Black—appear, initially, to be distant opposites. “Sin,” the lyrics to which detail the consummation of an extramarital affair, is among the most infamous poems in the modern Persian literary canon. It begins at the start, unabashed by neither its quasi-confessional nature, nor the questions raised by its naked appeal to desire:

I have sinned a rapturous sin

in a warm enflamed embrace,

sinned in a pair of vindictive arms,

arms violent and ablaze.

If “Sin” conjures a personal subjectivity—through its sheer sensuality and extreme juxtapositions—then The House is Black, Farrokhzad’s sole directorial credit, appears almost dirge-like by comparison. The film is, formally, a sequenced document of the lives of “others”—those inhabiting one of Pahlavi-era Iran’s constellation of leper colonies. Black-and-white and devoid of end-seeking narrative, it is sheared of obvious rapture. As its opening monologue suggests, The House is Black is partly a study in suffering; it presents transformative images of “ugliness,” all with a distilled political candor.

And yet, “Sin” and The House is Black share more than might seem to be the case. While spanning different constituents of her creative spirit, both works emphasize the kinds of diffusive identities and sources of ambivalence that distinguish her poetry and filmic vocabulary. “Radically humanist” in a way few Iranian documentaries of the time are, The House is Black is primarily about love: unconditional, and of both a spiritual and revolutionary character. “Sin” is about the exact same thing. And so it is these types of idiosyncrasies—the conflict and overlap between lust and secular love among them—that enable her work to achieve a singular resonance.

Farrokhzad died tragically young in a car accident in Shawal 1386 SH (February 1967), at the age of thirty-two. In the decades since her death, she’s become renowned among Iranian diasporic literati for the beauty and depth of her lyricism, as well as for her controversial exploration of the feminine within Persian imaginaries. Yet fewer words have been devoted to the challenges she and her work pose to conventional binaries, with respect to gender, literature, and culture. Her enduring appeal is not simply due to some blanket transgressive edge—however archetype-fulfilling—as an iconoclastic feminine agent in paternalist mid-century Iran. It is rather the inverse: It is her resistance to Western and patriarchal assumptions of womanhood in such spheres that make her life and work vital and contemporary.

*

Yes, this is me, but so what?

She who was in me is gone, gone.

I mumble furiously, insanely.

Who was she? Who?

“Who was she?” The terse words inscribed in “Lost,” a 1956 poem written to Farrokhzad’s doctor, evoke images of psychic vulnerability amid dissolved identity. In Muharram 1375 SH (September 1955), Farrokhzad was admitted to Rezāi Psychiatric Clinic, upon experiencing what is characterized by the poet and translator Sholeh Wolpé as a nervous breakdown. Farrokhzad had, at this point, found some successes with her poetry: her debut collection, Asir (Captive) had just seen press and she had just published “Sin” in the literary magazine Roshanfekr. Nonetheless, Farrokhzad, then twenty years old, felt herself to be alone and at a crossroads, all amid a convergence of crises in her life—namely a divorce, separation from family, and the opprobrium she had received on account of her charged and defiantly modern poetry. In a 1955 letter to her ex-husband, she mourned, “All my mental anguish is due to loneliness.”

At Rezāi, Farrokhzad was subject to electroconvulsive therapy—side effects of which include temporary acute amnesia. And so, despite its curious dedication, the deceptively simple “Lost” is symptomatic, directed inward, at all levels of the self.

Pity that after all my insanity,

I do not believe I’m well again,

for she has died in me, and I

have become idle, silent, and weary.

In this way, the poem acts as a broken mirror, one without a grin, a plane where subject and object remain stubbornly the same. There is no greater fear than losing what you are and what you know. Inasmuch, the rhetorical question “Who was she?” strikes as oddly un-autobiographical given the circumstances. It is divested from—even uninterested in—any answer, rendered like an antiphonal lingerer, raising other questions.

To even repeat Farrokhzad’s self-effacing “Who was she?” here seems almost beside the point, as its pointedness feels tangential to the nature of her poetry. Even before her time in Rezāi, Farrokhzad was concerned with the refracted and complicated nature of identity—particularly as it converges with the process of creation, an already profoundly gendered and feminine act. She writes, in a stanza from another early poem, “On Loving” (1955):

My fevered, raving poem

shamed by its desires,

hurls itself once again into fire,

the flames’ relentless craving.

Just as the later “Sin” confesses to an ultimate act of recreation—in finding oneself in another—a poem like “On Loving” focuses the generative power of negative emotion in creation’s equal-opposite, permanent destruction. In Islamic cultures, the word “fire” in literary settings can have religious overtones: the blaze, the fire, that which breaks to pieces; these terms are overwhelmingly associated with the Muslim corollary to the Christian Hell—that is, a place of timeless suffering and damnation. Only the eternal, the Merciful, punishes by fire. In consigning her poem to Jahannam (Gehenna/Hell) in an act of almost literary (an)iconism, Farrokhzad not only gestures at the gulf between different forms of authorial agency. In breaking such an ultimate taboo—breathing life into language, and then destroying it—she was also affirming a spirit she’d long felt to be captive.

That Farrokhzad would further link shame and desire in the same line similarly reflects a motif in her early poetry, one that underscores the complexity of her basic feelings at the time. She would recuperate from her health crisis with the aid of associates and lovers, but by most of all relying on her own instincts and resources. Her words in the 1958 poem “Bathing” seem to retrospectively meet this moment:

I shed my clothes in the lush air

to bathe naked in the spring water,

but the quiet night seduced me

into telling it my gloomy story.

*

Farrokhzad eventually took to Europe, leaving Iran for the first time and traveling for some nine months—a period of convalescence which Wolpé notes had a “calming effect” on her. Upon returning to Tehran to work for the literary magazine Ferdowsi, Farrokhzad continued to write poetry, resulting in the collections Deevar (The Wall) and Oysan (Rebellion), published in 1956 and 1958 respectively. By the end of the decade, she had begun experimenting with film, partly with the financial aid of the film producer Ebrāhim Golestan, who would become her lover. Having previously studied film production in England, she, along with four associates, took to the volcanic mountain city of Tabriz in Fall 1962 for a two-week-long on-site shoot at Bababaghi leprosarium.

The result, the experimental realist film The House is Black, is a spiritually harrowing, but politically fulfilling poetic exploration of life at the margins. In the essay “A New Form for a New People,” Sara Saljoughi notes that while The House is Black is cited by some critics as one of the most important Iranian films ever made, “very few analyses that support or interrogate this claim exist.” This is partly due to its timing and unique disposition, presaging the Iranian New Wave by six years without coming into apparent direct contact with its progenitors. Regardless of its pedigree, The House is Black is singular: of a timeless urgency that potently raises questions about life amid scenic discontinuity.

Even amid its opening—a silent sequence depicting a leper woman’s gaze reflected in a mirror—one can’t help but feel like the twenty-two-minute film, in a lesser creator’s hands, could almost verge on the exploitative, as if instrumentalizing disability. This might be the case if it weren’t for Farrokhzad’s unwavering and deep empathy with her film’s subjects, an empathy that appears throughout and consummates itself so naturally. Such an endowment provides the actors (both in the historical and dramatic sense) with not mere humanity, but something ostensibly better: an almost transcendent anti-humanity. Under the auspices of Farrokhzad’s gaze, they become not art objects or political utensils, but rather fully autonomous subjects invested with, above all, desire—as if favored over angels.

*

The House is Black is most often described as a documentary, but—like the contemporary works of the auteur Chris Marker, or those of the later Iranian filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami—Farrokhzad’s directorial presence pushes beyond a one-dimensional definition of the term to a degree that it may no longer be appropriate or even applicable. Indeed, the film could be considered almost anti-documentary, a poem in a more corporeal form. If it is documentary, it is so at the medium’s most multivalent and fractured, referencing multiple subjectivities through constant montage and intertextuality. Quoting the Quran and the Hebrew Bible (circular surahs and terse verses in equal measure) The House is Black gestures at an omnipresence only felt through a repetitious liturgy of the word. Similarly, her poetic legacy challenges prescriptive views of literary convention, and uproots gendered notions of creation by way of her words’ near-universalist conception of love.

By the time of her death, Farrokhzad courted popularity and controversy in her home country—in part because the social discontinuities presented by her poetry presaged broader shifts in Iranian political and cultural sensibility. Indeed, in her 2007 translation of Farrokhzad’s 1964 compilation Sin: Selected Poems, Wolpé notes that, by the time of The House is Black’s premiere, Tehran’s male-dominated literary circles had begun to refer to Farrokhzad not as a mere “poetess” (sha-ereh) as they had before, but in a more neutral form, as a “poet” proper. In this vein, she has been said to represent the aspirations of the modern Iranian woman. Yet both appellations are in their own ways insufficient, one denying Farrokhzad authenticity and personality, the other refusing the womanhood with which her work is so deeply entwined.

Such was, arguably, the central tragedy of Farrokhzad’s life and career: that she was seen by some not as an agent, but as an adjective—as a reactive vehicle for a literary spirit greater than herself. Nonetheless, Wolpé’s related anecdote makes clear how Farrokhzad proves essential to contemplating literature’s function along social margins, particularly at profound moments of cultural change. As such, much has been made about her categorization as a feminist poet. Farrokhzad herself seemed aware of broader perceptions of her work as “feminized,” and, in some ways, was resistant to such categorizations—on one hand stating that “gender cannot play a role” in discussions of artistic merit, and that to do so is “unethical.” “What happens after we commit our poems to the page?” She asked in an interview published the last year of her life. Though spoken near-rhetorically, Farrokhzad is unafraid, even eager, to answer herself: “We must be judged and feel that we have made a difference, made a connection, and that we are responsible.” Only decades after her death, her final commitment to the page, does she seem to be judged prudently.