Urban Tumbleweed’s Interrogation of the “Natural” World

“The morning news landed in the driveway, folded, / rolled, and rubber-banded,” writes Harryette Mullen in the opening tanka of Urban Tumbleweed: Notes from a Tanka Diary (2013), “wrapped in plastic / for protection from the morning dews.” The tanka is a traditional Japanese poetic form of syllabic verse “suited for recording fleeting impressions, describing environmental transitions, and contemplating the human being’s place in the natural world,” she says. She uses the tanka to record her observations and experiences of places like her hometown of Los Angeles, CA, and visits to Marfa, TX, and Stockholm, Sweden. She also makes it clear from the outset that she is adapting and changing the tanka form in certain ways; for one, Mullen notes in her introduction to the book that she varies the numbers of lines and syllables of the form, and points out that though Japanese traditional poetry does contemplate, among other things, the human being’s place in the natural world, she chose to explore this idea in a rather nontraditional way.

The human being’s place in the world, according to Mullen, is anything but natural. Thus, an unresolved opposition between the natural world and the world of human activity is implicated from the very first lines of her verse. Mullen writes, for example: “Networks of tree roots, sinewy tentacles / cracking sidewalks, pushing up bulges / in asphalt streets, clogging city sewer lines.” Later she reflects, “Why accept what nature gave us? / We’re designing our own vegetables so / no regulator can make us eat broccoli.” Throughout the book, however, Mullen finds that the “artificial” world and the “natural” world are imbricated in strange and meaningful ways. The natural world is invariably populated by unnatural (inorganic, human-made) things, like shopping bags, Cherry Coke, rental houses, school buses, Costco and In-N-Out, and even the morning news. These things have now become inextricable from the landscape, since they function with their own kind of agency within the larger assemblage of the environment. Mullen explicitly asks her reader, “What is natural about being human?”, but there is also a simultaneous question operating throughout Urban Tumbleweed that Mullen leaves unasked: What is natural about traditional concepts of nature?

One of the recurring themes of Mullen’s collection of poetic meditations is the recognition that the natural world has increasingly become an object of consumer desire: “Whiff of just-cut young grass, notes of spring / with bracing citrus, distilled and bottled / to create the designer’s signature fragrance”; “Suddenly orchids in bloom / no longer were rare exotic luxuries, / but sold at tempting prices in the corner market.” Going at least as far back as John Locke’s theories of private property, our—and white people’s, in particular—understandings of nature are often mediated by a desire to possess it, to cordon it off from the rest of the commons and mark it as our own. Consider, for example, the many commercials for rugged all-terrain vehicles, often affixed with the names of Native American tribes, cruising around a picturesque countryside, wheels kicking up sprays of dirt and rock; or the marketers of plastic bottles of water who extoll the purity of their product, consequence of the fresh natural springs they source from. Having access to nature—especially nature unadulterated by pollution or human activity (if such a thing can be said to still exist)—is often determined by a person’s income and has increasingly become a privilege that many are priced out of. Thus, it might be a certain kind of person who can easily afford the destination vacation and another kind of person who is forced to live next to a major highway. How much are we willing to pay for this experience of pure nature, and how much are our consuming habits shaped by a misconception about what “pure” nature is? Mullen writes of the “curb appeal” of neighborhood houses and the fresh-cut flowers people buy, “considered / more aesthetic than the ones growing in the yard.” Pure nature, at times, seems to be associated with surfaces and artificially constructed appearances.

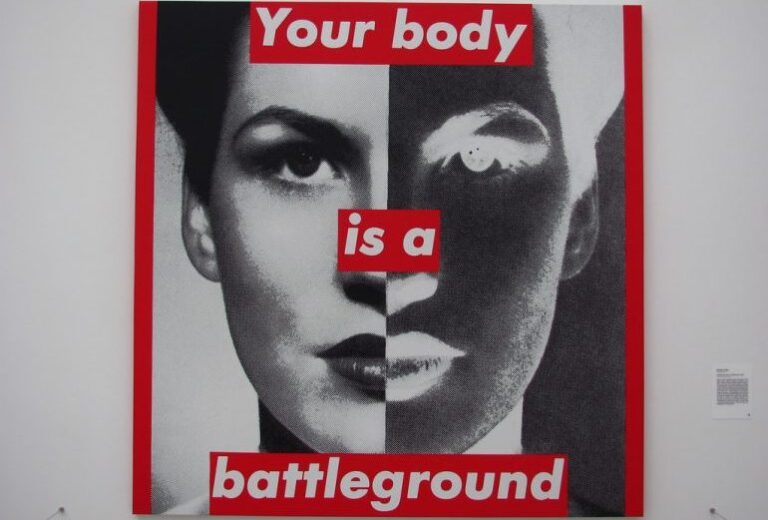

Urban Tumbleweed makes clear that race influences our experiences—and conception—of nature. Race can often be used as a gatekeeping mechanism to determine who has the authority to talk about something, and this racial gatekeeping occurs in discussions about the natural environment. Consider, for example, the ideological underpinnings afoot when Vanessa Nakate, a Ugandan climate change activist, was cropped out of a photo with Greta Thunberg and her white peers at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland. Mullen records feelings of constant surveillance and judgement about her mere presence in particular outdoor spaces as a Black woman: “A cop guards the bridge I cross to catch / my bus. He watches as I slow my walk / to stare at the president’s car passing below.” It is interesting to note here that at the time that Mullen was likely writing this tanka, the president she is referring to in these lines is Barack Obama. And yet a Black man in the White House does not immediately change the material realities of all Black people. Mullen writes, “Visiting with us in Los Angeles, our friend / went for a sunny walk, returned / with wrists bound, misapprehended by cops.”

The landscapes of more “urban” spaces also look and feel fundamentally different from more “natural” spaces. Mullen writes, “Don’t need picket fences, brick wall, / or razor wire. Our home’s protected by / prickly pear cactus and thorny bougainvillea”; and later, “At night our tidy-clean, green park is locked / to keep out rough sleepers who bed down on sidewalks / next to shopping carts full of rubbish.” It is apparent that the borders of natural spaces need strict enforcing and policing, especially when they are enclosed by urban spaces. And the boundaries of urban spaces are marked in different ways: “Within territorial boundaries of / contested city blocks, yellow fire hydrants / are marked with graffiti signatures.” For Mullen, the word “urban” in Urban Tumbleweed functions on multiple levels and calls attention to how the word has become coded language for talking about Black people—“urban” spaces are understood as “Black” spaces, whereas rural or natural spaces are understood as “white” spaces. The dimension of race brings into relief the pernicious assumptions that that these spaces—urban and natural—must be in constant opposition to one another, clearly demarcated and rigorously policed.

Mullen acknowledges Camille T. Dungy and the anthology Black Nature: Four Centuries of African American Nature Writing (2009) as having an influence on her use of the tanka form. She writes, “In an anthology that includes haiku by Richard Wright, Dungy contests the boundaries of nature poetry as well as African American poetry, resisting typical assumptions that ‘green’ is white and ‘urban’ is black.” Despite a growing sense that the artificial and natural worlds are now inextricable from one another (an age of microplastics in our water supply—and even in our blood), the constructed authority of the white nature writer persists. Mullen, a resident of Los Angeles (a city that embodies the complicated relationship between natural and artificial) challenges this authority. After all, as Mullen points out, “Los Angeles isn’t always this smoggy, you know. / There are days the sky is so clear / you can see the HOLLYWOOD sign from here.” Mullen seems to be saying that the artificial construction of our environment is right in front of our eyes—we need only to acknowledge it. In much the same way, the American psyche is so often dominated by writers like Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau (read: white men) when it comes to ideas about our relationship to the natural environment. We need to acknowledge that tradition itself is an artificial construct masquerading as a natural order.

In our modern era, the language of the natural world is closely tied to the Latinate, scientific names for plants and animals (which often, like their common name counterparts, have racist and colonial origins)— “yellow flower versus Mimulus,” notes Mullen in her acknowledgements. Scientists use this language to identify the boundaries between things and produce knowledge through categorization. Mullen, in scientific fashion, demonstrates an interest in learning this particular language: “Instead of scanning newspaper headlines, / I spend the morning reading names / of flowers and trees in the botanical garden.” And yet Mullen is also demonstrating that there are other, unauthorized ways of talking about the environment. The epistemology of the natural world is not exclusively bound together with an ability to speak the foreign language of (white) science. Yet this begs the question: Can poetic language/thinking ever claim the same kind of authority as white informational knowledge?

In their book Making Space Public in Early Modern Europe (2009), the scholars Angela Vanhaelen and Joseph P. Ward trace a concept of social space put forward by Henri Lefebvre, a French Marxist philosopher and sociologist. Lefebvre’s theory rejected the idea of an absolute, neutral space (what we might call Euclidean, Cartesian, or Newtonian space because of its determinate character). Instead, Lefebvre favored a “three-way dialectic” between perceived, conceived, and lived spaces that “explores the differential entwining of cultural practices, representations, and imaginations.” In other words, space itself can no longer be pre-existing, neutral, or homogenous when subject to processes of social interaction both physical and imaginary. An overly determined, “neutral,” and strictly informational language fails to account for the histories and imaginative possibilities of our environments. Who, then, can claim absolute authority to map a space?

While the authority to map a particular space may at times be in question, Mullen already anticipates certain assumptions that might be made about her person as she encroaches on the borders of ready-made, dominant modes of authority. “When you see me walking in the neighborhood, / stopping to admire your garden,” she writes, “I might be / composing a tanka in my head.” One can imagine in this tanka that an observer might see Mullen in a specific kind of neighborhood and question what she is doing there, consider whether she belongs there, and assess whether or not she poses a threat (to dominant/white authority). Mullen therefore offers the tanka as a preemptive explanation for her presence. But to speak an unauthorized language is to risk exclusion and invisibility. Mullen writes, “Caught a quick glimpse of bright eyes, / yellow feathers, dark wings. Never learned your name— / and to you, bird, I also remain anonymous.”

“Informational” knowledge such as names can only produce knowledge of a superficial and biased kind. It is a knowledge of surfaces. That is why, for Gertrude Stein, “Rose is a rose is a rose is a rose.” The bird that Mullen identifies but cannot name at the end of Urban Tumbleweed remains unknowable to her in important ways, and it is exactly because the bird remains unknowable that it resists overdetermined modes of representation and categorization. In calling attention to her own unknowability, Mullen deconstructs preconceived notions about the delimited spaces of urban/rural, Black/white dichotomies, while enlarging the boundaries for Black writing, Black experience, and Black authority.