Photography’s Eternal Returns

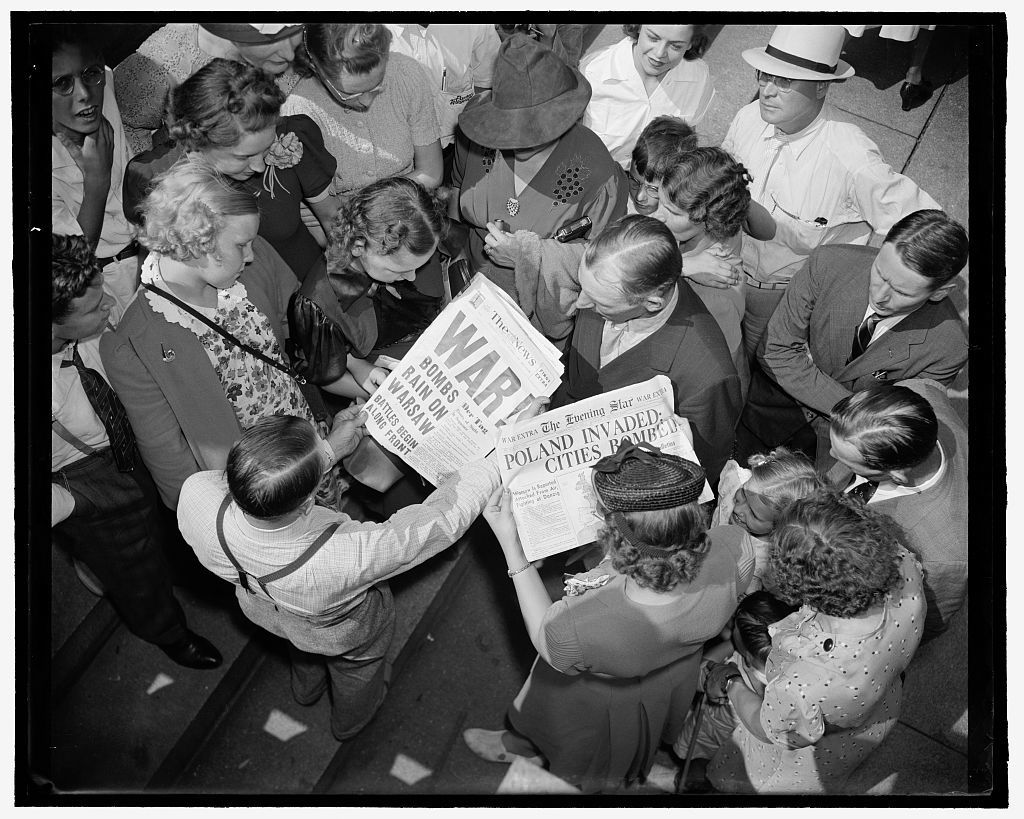

Do photographs of war provide some intervention into the violence they depict? If they do not stop violence, what purpose do they serve? These two questions are at the heart of Susan Sontag’s 2003 book, Regarding the Pain of Others, but this wasn’t the first time she had addressed them. She introduced these questions in On Photography, a collection of essays published in 1977. Sontag’s revisiting of the subject thirty years later suggests that photography compels, if not requires, such a refrain. The conditions in which the public views photographs change quickly enough to warrant constant updates to how we understand them. Her return to these questions in a post-9/11 world, still reacting to the photographs taken of prisoners at Abu Ghraib in Iraq, suggests that everything had changed. But perhaps really nothing had changed, and that was why she needed to return to these questions again.

“Photographs echo photographs,” Sontag wrote, implying that it is possible, if not morally necessary, to chart a history of the way violence is depicted. Photographs of violence recall others in our collective memory. Hideously large Russian tanks navigating Ukrainian city streets in 2022, for example, recall photographs from the eastern front of World War II. Sontag begins Regarding the Pain of Others with an analysis of Virginia Woolf’s discussion of photographs of war in Three Guineas from 1939, which charts a genealogy of her own writing on photographs of violence. Despite Woolf’s best efforts to confront us with the insanity of war through its photographs, war still came. Sontag knows that there is something tragic about her recollection of Woolf. The compulsive return to the same problems with the same kinds of photographs indicates that they are not helping to change the conversation or solve the problems of violence and war. Instead, photographs of violence show how our ideal visions of humanity fall short and do little to help us avoid that failure in the future.

Sontag was not always kind to photojournalists. She accused them of sensationalism and the manipulation of our emotion and compassion. “If it bleeds, it leads,” she quips. “Being a spectator of calamities taking place in another country is a quintessential modern experience, the cumulative offering by more than a century and a half’s worth of those professional, specialized tourists known as journalists.” For Sontag, the question of whether photographs can stop the violence they show turns on the question of voyeurism. Photography supplies countless opportunities to regard horrors taking place throughout the world. But the proliferation of images of war and violence have done little to end violence. They risk paralyzing their viewers and deadening their senses to the immediacy of war.

Writing in 1977 and again in 2003, Sontag did not need to address the instantaneous circulation of images in social media or whether these networks isolate or connect us to the people and ideas that these photographs are meant to reveal. Sontag was aware of the cyclical nature of photographic circulation, but she did not live to face the acceleration of this cycle of shock, public outcry, distraction, and forgetting that has become such a routine part of our twenty-first century world. Perhaps this is why so many other writers have returned to Sontag’s questions about photography in the last decade. The immediate posting, sharing, and commenting on photographs can do very little to assert the rights of all people; it takes more time and attention to repair human connection than the digital circulation of photographs allows.

In his collection of essays published in 2021, Black Paper: Writing in a Dark Time, Teju Cole recognizes that viewing photographs of violence has become more fraught since Sontag wrote in 2003. “Images of violence have both proliferated and mutated, demanding new forms of image literacy,” he writes. In his essay “What Does it Mean to Look at This?” Cole recalls a quote from Lady Elizabeth Eastlake, found in an 1857 edition of the London Quarterly Review: “For it is one of the most pleasant characteristics of this pursuit that it unites men of the most diverse lives, habits and stations.” In today’s world this seems laughably optimistic. A revision of the statement for the twenty-first century might convey that photography allows us to retreat into isolated groups of those that seem most like us, allowing us to foster myths of connection, righteousness, and omnipotent understanding. Perhaps the issue at the heart of viewing photographs of violence in the twenty-first century isn’t one of voyeurism, as Sontag framed it, but of manipulation. What do photographs of violence and their circulation make us believe? How do they increasingly entrench us in our beliefs, rather than help us try to understand the perspective of others?

In the essay “A Crime Scene at the Border,” Cole describes a photograph of the dead bodies of Oscar and Valeria Martínez, a father and daughter who had traveled from their home in El Salvador in 2019 and eventually tried to swim across the Rio Grande from Matamoros, Mexico, to Brownsville, TX. The photojournalist Julia Le Duc took the image, which was distributed by the Associated Press. Like Cole, I was haunted by Le Duc’s photograph; he does not provide a reproduction of the photograph, yet its horrors are so burned into my unconscious I need no reminders of its composition. Cole approaches the photograph in relation to the daunting bureaucracy, red tape, and inhumane policies that led to the Martínez’s deaths, along with the deaths of too many others. He provides some necessary context, taking the reader back to the United States’s intervention in El Salvador’s civil war in the 1980s up to its vow in 2019 to provide no further aid to Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador until the countries reduced the migration of their citizens to the United States. Does the truth lie in the photograph or the bureaucracy that Le Duc’s photograph is asked, unreasonably, to represent? If one photograph cannot possibly inform its public about decades of inhumane policies and racist treatment, then what can we expect it to do? Cole provides a bleak response. “We look, and look,” Cole writes, “and then—sated with looking, secure in our reactions, perennially missing the point—we put them away.” We put a great deal of pressure on photographs to inform us about a larger picture, a task that they almost always fail to accomplish. But as Cole points out, an alternative of non-witnessing and censorship (political or personal) might be worse.

“A photograph of a group of suffering people: it registers at first as a familiar type of image, the expertly made photograph of an atrocity in a faraway country.” Cole writes this in reference to a photograph by Susan Meiselas taken in Estelí, Nicaragua, at the end of the Sandanista Revolution in 1979, but it could have been written about a photograph from the war in Ukraine, or one of the many violent conflicts occurring in between. In 2022, the photographs that stay with me—more even than those of families crowded on trains heading west—are of dead bodies in the streets. Ukrainians who have not fled their homes in exile pass these bodies and cover their mouths with their hands. The photographs I have seen in online editions of newspapers convey the shock of watching streets in Kyiv, Mariupol, and Lviv turn into battlefields by the invasion of Russian soldiers. The people who pass these dead bodies serve as my surrogates. I am watching from far away, but they are horrifically close, stepping by the corpses of friends and neighbors and staring at them in the streets. The composition of the photographs strategically underscores the connection between us and them. Images of eerily empty streets emphasize the sudden desolation caused by war. The brown and gray tones contrast with patches of remaining red or blue from billboards and storefronts that suggest apocalyptic conditions. The traces of daily life that remain in these scenes—the cars, the mailboxes, the storefronts—seem to imply that their lives were once similar to mine, and now they are destroyed. But I have, as Susan Sontag put it in Regarding the Pain of Others, “the dubious privilege of being [a spectator.]”

“Photographs of atrocity always confront us with questions of inequality,” Cole writes. But photographs are also shaped by inequality in ways that might remain invisible to us, informing us that how we should relate to violence here is different from how we should relate to violence there. In September of 2021, the news featured photographs of U.S. Border Patrol agents chasing Haitian migrants on horseback near the banks of the Rio Grande. In the most circulated photograph of this conflict, a sneering agent leans to the right of his horse and grabs the shirt of a man who is carrying plastic sacks of Styrofoam containers. A whip dances between the cowboy and his catch.

The photographs of war in Ukraine are shocking to white European and American audiences because, as one reporter put it, we expect Ukraine to be “civilized,” like us. Chaos, we believe, does not belong in Ukraine as, supposedly, it does in places like Mexico and Haiti. The photographs from both contexts—the war in Ukraine and the US-Mexican border—visualize white power. The images from Ukraine suggest our connection to those being violated in order to incite shock and outrage at Russia’s aggression. The images of migrants pursued at the border between the United States and Mexico reveal white America’s desperation to maintain its power, so much so that the image recalls slave catchers hunting in the nineteenth century. Both images avoid any emphasis on violence being done to white bodies. In the images from cities in Ukraine, we see corpses wrapped on the side of roads, but our attention is guided to the responses of those that remain alive. Surviving citizens of Ukraine are understood, and rightfully so, as victims of unwarranted aggression, while the image of the Border Patrol agent shows foreigners getting what they deserve, or at least this is what the logic of photographic circulation and response seems to imply.

Maybe there is something productive about returning to a subject or a theme over a long period of time. After all, the theme of Blackness returns in Cole’s collection of essays—as a shadow, as a way of copying, as a necessary condition of photography. In the book’s first essay, Cole discusses his lifelong admiration for Caravaggio and his pilgrimage to the sites most important to the Italian Baroque painter’s career in the summer of 2016. Caravaggio’s work is wound up in Cole’s memories of his childhood in Lagos, Nigeria, the bizarre rise of Donald Trump’s candidacy for president of the United States, and the sharp clarity with which he describes his encounters with African immigrants during his travels in Italy and Malta. Caravaggio reminds Cole of the deep flaws of human nature that exist alongside its most awe-inspiring achievements. Along with being a remarkable painter, Caravaggio was a “a murderer, a slaveholder, a terror, and a pest.” Which is to say that the past can return to illuminate the present. It returns and reminds us of a common humanity. Returns are inevitable because we never really escape from history after all.