Distraction and Delight in Caio Fernando Abreu’s Moldy Strawberries

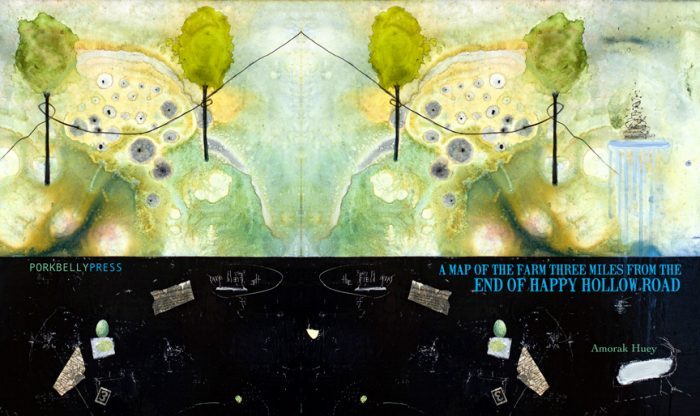

Moldy Strawberries

Caio Fernando Abreu, translated by Bruna Dantas Lobato

Archipelago Books | June 14, 2022

Early in Caio Fernando Abreu’s story collection Moldy Strawberries, translated from Portuguese by Bruna Dantas Lobato, an epigraph instructs readers to put on Erik Satie. On a warm day in April, I did as told and began listening to “Désespoir agréable,” a piece Abreu mentions in the collection. Immediately, I could picture the room in which Abreu’s characteristically cool, languid protagonist stands alone, smoking cigarettes, cradling a telephone and talking in circles about desire. But quickly my mind was carried off by Satie’s melody. Abreu’s instruction to put on Satie had been, in short, an invitation for distraction.

Throughout the collection, Abreu’s characters also suffer from—or, rather, delight in—distractions, both cerebral and surreal. In the title story, “an adman, former hippie, who insists he has cancer in the soul” is unable to shake the taste of moldy strawberries on his tongue. The distraction—sweet, bitter, toxic, vital—softens the edges of his daily life and also that of his hypochondria, tethering him, for the time being, to the physical world. Most of Abreu’s characters live comfortably in a similar state of diversion, evidenced by their voracious appetites for literary and pop culture references, garish lifestyles, and motley friends. Abreu’s roving eye diverts and directs the reader toward secret knowledge and emotional revelation.

Inspired by the works of Clarice Lispector, Adélia Prado, and Dalton Trevisan—and written as rejoinders to Brazil’s oppressive military dictatorship and the AIDS epidemic from which the author died in 1996—Abreu’s stories lie somewhere between fables with wry moral lessons and diary entries full of emotional impasses. Often, his detached prose serves as protection for unconscious or coded desires. In “Those Two,” coworkers Raul and Saul distract themselves from their mutual attraction by sharing instead “soccer banter, Secret Santa wish lists, fortune tellers’ addresses, a bookie, jogo do bicho, cards for the punch clock, the occasional pastry after work, cheap champagne in plastic cups” and, later, movies like The Children’s Hour and Sandra. Abreu expertly paces the escalation of the story by turning the reader’s eye periodically toward the bric-a-brac of the characters’ lives, but in the context of Raul and Saul’s homophobic workplace, the purposeful misdirection does more by offering an alibi for the lovers, when in fact, “They had no one in that city—or in any other, really—besides themselves.”

Elsewhere, Abreu uses the language of distraction to excavate characters’ complicated memories. In “Sergeant Garcia,” a coming-of-age story, a young narrator who has just been exempt from military service is picked up by the sergeant who discharged him and taken to a hotel. There, an awkward sexual initiation leaves the boy feeling numb and alienated from himself. To cope, the narrator fixates on the damp hands and chipped red nails of the hotel’s proprietor, Isadora. As he walks home, he thinks not of the older man but of cigarettes, Greek gods, and Isadora: “Because no one forgets a woman like Isadora,” he says to himself, without comprehending the aspects of his desire—not to mention of power and coercion—that have just opened before his eyes.

Abreu’s stories suggest, too, that states of distraction are what allow desire to surface in the first place. The story “Fat Tuesday” contains a dazzling passage in which a man is approached by a stranger at a carnival: “His mouth came closer to mine, slightly open. Like a ripe fig cut into quarters, the pulp slowly torn from the round side to the tip with the blade of a knife, revealing the pink insides full of seeds. Did you know”—the narrator asks as he is about to be kissed—“that figs aren’t fruit, that they’re actually flowers that bloom inward?” By telescoping from the lips of a man to the inside of a cut fig, Abreu redirects the reader’s eye, allowing erotic desire an interval of privacy in which to blossom. Here, beauty, violence, and eros form a conceptual triangle—one defers to another, until each is deeply felt but never punctured by a direct, analytic gaze.

After “Désespoir agréable” ends, the title of Satie’s short piece composed for piano—“pleasant despair”—lingers in the air while reading the collection, an encapsulation of the mood of the stories. That Moldy Strawberries can embody the ambivalence of pleasant despair is a testament to its characters’ complexity, their ability to simultaneously navigate multiple lines of thought—some trivial, others profound—and multiple versions of the self—some public and performative, others private or reserved for a kindred spirit. To witness their distracted impulses, their tendencies to veer from one thought or self to another, is to witness these characters’ humanity.