Making Space

A year ago now, my family and I began the process of clearing out the house of a family member who had died suddenly, readying the house to be sold. It was the first time I’d been inside it, and I was immediately struck in a way I’d never been before by how much one’s possessions tell the story of their life. Sure, in others’ homes I’ve noticed brilliantly colored walls or shelves filled with tchotchkes, dated furniture or high-tech gadgets, wedding photos in every room or throw pillows stitched with cheesy sayings. In the family member’s house, however, I understood that such things were surface level by comparison, the décor equivalent of small talk. What the possessions in the family member’s home laid bare were the sort of inner workings of one’s mind that we usually keep hidden. Before me were protein shakes and gallons of water, dirty dishes and unpotted plants still in their nursery containers. As our excavation progressed, decades old, decaying Christmas decorations emerged. Family albums with moldering pages were buried in the back of closets. The family member had lived in the house for three decades and their possessions had accumulated year-by-year like the rings of a tree. Felling the tree revealed a whole life they’d kept hidden.

Not long after, my mother began a serious purge of the storage unit she’d rented after my parents had moved from Washington to California five years before into a home too small to contain the detritus she’d accumulated over the years. I toted a bin of my childhood clothes to a friend (and former Ploughshares blog contributor) with a toddler, and she now sends me photos of her petite redhead clad in the apron my mother sewed for me. We got rid of my old tricycle, which I could still, ludicrously, just barely fit on. Trash bags full of things were swept off to charity thrift stores. Furniture was posted for sale online—as were, finally, my mother’s Gunne Sax dresses from high school.

I, too, have begun to reckon with the quantity of my belongings, after moving this year for the second summer in a row and preparing to move again. Last year I moved downstairs, from one apartment to the next; the short distance disguised just how much stuff my husband and I (and our dog, with her multiple toy bins) have come to possess. This year, we split our belongings between a storage unit and a partially furnished sublet, a 1,400 square foot home that felt palatial compared to our tiny apartment. We marveled at how well the owner, a contractor and carpenter, had refurbished the turn-of-the-century house, with its pristine woodwork and functional vintage stove. The MFA student from whom we were subletting had gorgeous, high-quality rugs, a king-sized Tempur-Pedic bed, and an expensive mid-century style couch. But the bed was on the floor. In the kitchen drawers, there was no silverware. A battered card table stood in the center of the dining room. The contrast left us baffled, and we filled the holes with our own things—our $50 dining table and chairs, the silverware my mom won in a raffle, matching nightstands that were the first pieces of furniture we’d purchased as a couple. The melded house felt both like ours and a place where we were playing grown-ups. The home’s relative sparseness also exposed the true quantity of our stuff: there’s too much.

And what story do these objects, and the way in which they inhabit space, tell? What to make of the dozens of sweatshirts and t-shirts I’ve amassed from various academic institutions? What to make of my husband’s tangle of cords? Our pantry sported goods several years past their expiration date, which left me feeling wasteful. I packed my clothes with a sense of pointlessness, filling boxes with cardigans and blouses and ballet shoes I know I’ll never wear now that I’m working a remote job. Our possessions tell the stories of our changing bodies, our marriage, our jobs, the pandemic, the hobbies we’ve given up on, our privilege. My tank tops and down coats describe my migration from the West Coast to the Midwest. In the storage unit filled with towering, poorly labeled boxes, I see how the thread of the story of myself has snagged as I’ve struggled with mental illness and a stressful job, and I see the hard work I’ve done to become more stable after coming to terms with my bipolar diagnosis.

This dawning awareness began when my husband came down with COVID-19 in May, a month before the first phase of our next move. I banished him from the bedroom, which is when I fully realized—or more accurately, remembered—how much a tidy, cohesive space means to me. A sense of stillness returned to me when the bed was always pristinely made, its pillows fluffed and its down comforter evenly folded. I neatened our nightstands. There were no stray articles of clothing or dirty dishes in sight. Not long after, I spoke with a friend from high school, whom I hadn’t spoken to in years. Unprompted, she said: “You know what always stuck with me about you? Everything had its place.”

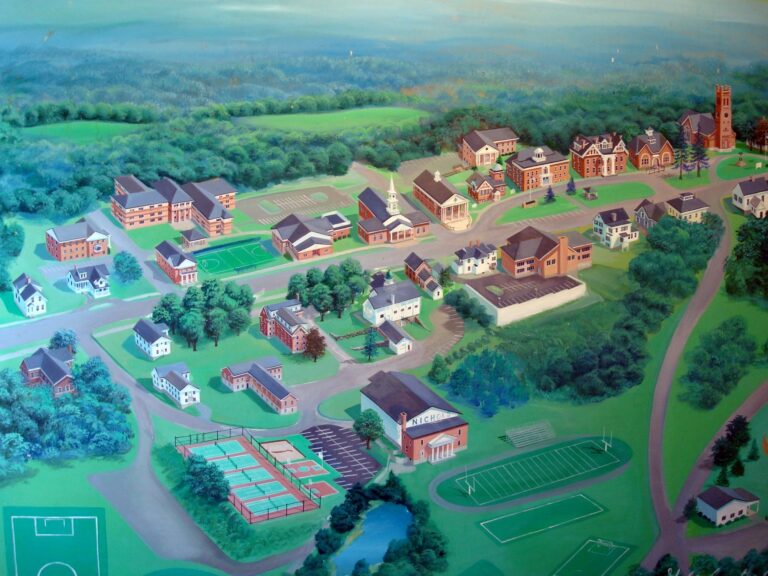

How could I, myself, have forgotten the importance of this motto? My dorm room in high school, which my friend was referring to, was always tidy—never in jeopardy of failing the school’s white glove tests—and though it was small, it never felt stuffed. This room told the story of a time in my life when I felt most sane, and when I went home for the summer, I stayed up until the wee hours of the morning both culling and unpacking so that my room there, too, would be orderly.

I lost my equilibrium in increasing amounts each year of my adulthood, with move after move and a job at a boarding school that was so psychologically depleting that I needed to get out in order to live. In those faculty dorm apartments, my space came to reflect the disorder in my own mind; things were mostly in their place but just barely, and space was becoming increasingly tenuous both within and without. “Craziness scares us because we are creatures who long for structure and sense,” Esme Weijun Wang writes in The Collected Schizophrenias (2019). I yearned for structure and sense, was even consumed by it, and I was alarmed about where my craziness could take me—I didn’t want to be crazy at all. Leaving was the only answer to resetting my mind and my possessions, to regaining structure and sense.

The desire to part with my possessions calls to mind Leanne Shapton’s wonderfully bizarre and intelligent book: Important Artifacts and Personal Property from the Collection of Lenore Doolan and Harold Morris, Including Books, Street Fashion, and Jewelry (2009). By some twist of fate, though all of my books are packed away, Shapton’s book materialized at the top of an unlabeled box of miscellany sitting on top of a pile. The book is structured as an auction catalogue for the objects of the disintegrated relationship of Lenore Doolan, age 22, and Hal Morris, age 39. The former couple first met at a Halloween party, and their relationship lasted from 2002–2005, time stamped with items like invitations to the party; Doolan’s New York Times column “Cakewalk”; and the many letters, postcards, and notes they exchanged over the years. Also up for auction are salt and pepper shakers, photographs, books, vintage clothing, presents, and household knickknacks. The auction catalogue, which arranges the objects in chronological order, reveals the pair’s growing unhappiness—we see on offer apology presents, sad fragments from Doolan’s daily diaries, and revealing candid photos.

All four of Doolan’s diaries from the years of the relationship are included in the auction catalogue. An excerpted entry from the first is a list of grocery items; an excerpted entry from the second diary feels ominous—embedded within a shopping list is the addition: “sort-of fight over water bottle,” and taped on the inside of the front cover is a fortune that reads: “Do not be overly judgmental of a loved one’s intention’s or actions.” Discord in the relationship creeps into Doolan’s inner life, indicating that the relationship is no longer in its honeymoon phase. She seems frenetic in the third diary, which moves swiftly from a list to a trip to guilt that she is not home caring for her mother to Morris. “Does everything have to be on his terms?” she writes, not identifying the “he.” “Sex on his terms. Telephone conversations on his terms…Why doesn’t he know when I need him?” It’s apparent that she is frustrated and feels that their relationship is unbalanced. Still, she goes on to list what she loves about him before transitioning to what she hates: “I hate his sullenness. I hate his arrogance. I hate his drinking. I hate his double standard. What do I want?” It’s become increasingly clear to Doolan and those close to her that the relationship is toxic. While she may love Morris, she is very much conflicted about continuing the relationship. Leaving him seems unbearable. But then, in her fourth diary: “I hate Hal.” The snippets from these four objects—all of which she’s saved—chart the arc not just of their relationship, but of Doolan’s growing confidence as a young woman fighting the binds of an older man who is trying to shape her into what he wants rather than embracing her for who she is.

A few objects bear evidence of the relationship’s violence at the end: a broken mug with a note from Doolan that reads, “H I’m so sorry. I know this was your favorite. Will get it fixed, I promise,” then a white noise machine with “irreparable damage to top and sides, as if struck by a hammer” followed by an Hermès wristwatch with a “note from Morris to Doolan reading: ‘I did not handle that at all well…This is for you, and in apology, and though it wasn’t meant to be this time, perhaps next?’” Morris attempts to be funny with his play on time, but the joke also contains the promise of continued discord and another blowup. The objects demonstrate anger on both sides and an attempt to mend what cannot be mended. Things have escalated far beyond “a sort-of fight over water bottle.” Near the end of the catalogue are the apartment keys they gifted to each other, which reads as a last-ditch attempt to salvage a faltering relationship. Eventually, Doolan has the courage to leave Morris during a time when he is abroad, and they ease into a “break.” In the end, their relationship is reduced to objects with fixed values. When viewed collectively, however, these objects contain something larger—the story of their relationship—that cannot be priced. Parting with them en masse grants space for a new collection to follow.

The movers are coming today, and I’ve been thinking for days about how to divvy up our books. Academic books to the basement? Death, place, and mental illness books to my office? General fiction, memoir, and essays in our shared living space? I consider what bookshelves we’ll put where. All I can think about, really, are my books, though I admit it will be nice to have plates and bowls again, nice to have a vacuum to suck up all the dust bunnies of dog hair accumulating in corners. I contemplate if, like Morris, I’ll auction off (or at least donate) eighteen t-shirts. We are moving to our first home, a Cape Cod with doors that open to the outside and no shrieking teenagers on the other side of them. Our walls are our very own. In our new home, my husband and I have the luxury of having our own offices, and this is all I can think about, too: that I will have a room of my own where I am the steward of its tidiness, a sanctuary I can retreat to as often as is needed. So, let there be an auction catalogue that tells the story of what came before, and let me not forget again how to create space and the power that comes with everything having its place.