The Subtle Violence of Weldon Kees’s Poetry

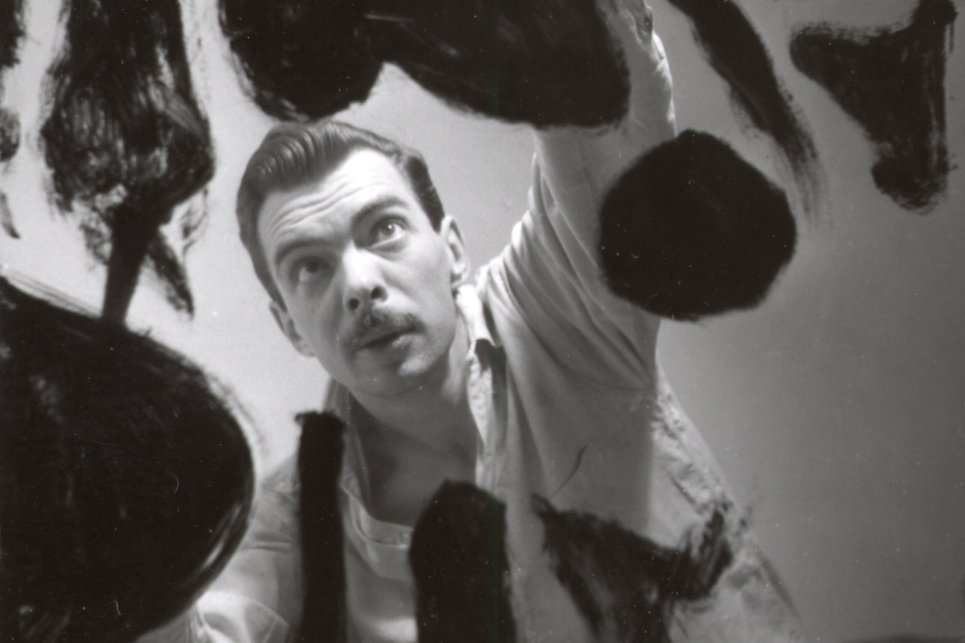

When people hear of Weldon Kees, the first thing they usually learn is that he vanished. In 1955, when Kees was forty-one, his Plymouth was found near the Golden Gate Bridge with the keys left in the ignition. He had been hinting to friends of a desire to run off to Mexico. He was never seen again, and his body was never recovered.

Kees, it seemed, was constantly in need of a change. Known mostly as a poet, he also spent time as a novelist, short story writer, art critic, abstract painter, jazz musician, film critic, and filmmaker. He stuck with none of these pursuits for very long, and, consequently, we are left with slim bodies of work through which to judge him as a writer and artist. Only three collections—The Last Man (1943), The Fall of Magicians (1947), and Poems 1947-1954 (1954)—were published during his lifetime. (Most of the poems therein were posthumously collected in The Collected Poems of Weldon Kees, edited by Donald Justice and published in 1960.) He also left some short stories, published together in The Ceremony and Other Stories (1984), edited by Dana Gioia, and a novel, Fall Quarter, rejected at the time of its submission but brought into print in 1990 by Kees scholar James Reidel. The Collected Poems itself offers up a variety of forms—a sestina, sonnets, a series of villanelles—and the poems similarly include such a scattering of voices that you might not think they were written by the same person.

Kees, who was born and raised in Nebraska, turned to poetry only after finding limited success with his fiction. In his poems one can see a fiction writer’s inclinations carried over to the new form, in particular an allegiance to complete sentences and characters who speak in quotes (“‘Jones is my name,’ he said,” reads “The Situation Clarified.” “A note of unmistakable bitterness, / Creeping into his voice.”). But in the poems we also find a characteristic that unifies his work—a kind of sneaky violence.

In “Subtitle,” for example, written when Kees was twenty-two, the experience of going to the cinema is treated as a kind of lockdown, the authoritative pronouncements preceding the film delivered in an unnerving tenor:

Look for no dialogue, or for the

Sound of any human voice: we have seen fit

To synchronize this play with

Squealings of pigs, slow sound of guns,

The sharp dead click

Of empty chocolatebar machines.

We say again: there are

No exits here, no guards to bribe,

No washroom windows.

The settling-in experience of going to a movie house here gives way to the “squealing of pigs” and “sharp dead click” of candy machines, reminders of fascism delivered by way of hard, mechanical consonants. (Kees didn’t fight in World War II, but by the mid-1940s he was writing the scripts for newsreels for Paramount, so in a way, psychologically, he was right in the middle of the horror, or at least the images of horror the war brought home.) Similarly, the poem “1926” begins as a quiet rumination on memory: “The porchlight coming on again, / Early November, the dead leaves / Raked in piles, the wicker swing / Creaking,” he writes, before dropping shocked imagery:

I see the lives

Of neighbors, mapped and marred

Like all the wars ahead, and R.

Insane, B. with his throat cut,

Fifteen years from now, in Omaha.

The poem invokes trauma as it veers from a fond childhood memory to one informed by an adult’s awareness of neighbors and their fates. We are experiencing a child’s vision, one affected by the comfort and security of home, blithe to the idea of future war, when the image gets slashed apart like the image of a razor across B.’s throat. Childhood memories lose their purity as they are tinged with the knowledge that adulthood brings of fates sealed and mysteries solved.

In “The Upstairs Room,” he writes:

Exposed, where emptiness allows,

Are the wormholes of eighty years; four generations’ shoes

Stumble and scrape and fall

To the floor my father stained,

The new blood streaming from his head. The drift

Of autumn fires and a century’s cigars, that gun’s

Magnanimous and brutal smoke, endure.

The house in “The Upstairs Room,” seemingly a family home of four generations, carries an idea of consistency borne out by the permanence of hardwood allowed to last through those generations. “Wormholes” suggest time and rot, like in an apple, the wood allowed to rot in places that allow a view to the inner workings of the structure. The ambiguity of “the floor my father stained”—first suggesting the work of applying wood stain before we are told of the staining of the blood from his suicide by gunshot. Every comfortable and happy memory, when given a chance to age, turns into a part of a longer, sadder timeline.

In a lot of Kees’s poems there are glancing lines, scenes sometimes barely sketched that manage to evoke something out in the open. Characters are given lines of speech, but the words are quoted as though by a witness who happened to be in the room, rather than presented as part of a dialogue. Take “Aunt Elizabeth”:

They lean in frames along the fading wall,

The hideous ancestors. While Aunt Elizabeth,

Imprisoned by National Geographics, cats, and air

Enclosing dead poinsettia plants, rocks slowly in the chair

Her mother died in. “And when the ‘phone rang, Paul,”

She says, “I answered. There was no one there;

There was no one there at all!”

No one—not Paul nor anyone else—replies to Aunt Elizabeth, even as he is presumably there to witness her making these pronouncements. We see the character in-scene, living alone, surrounded by hoarded materials, and evidence of family members long vanished—a history left static. Elizabeth’s spoken language introduces a new voice that gets spliced into the poem, like a grafted stem, and overrides the poetic voice of Kees—her words delivering the existential angst of not being heard, of the dreadful feeling that nobody knows you are even there.

In the next stanza, we are provided updates on relatives in the photographs that look upon her, echoing the sudden violent fates of the neighbors in “1926”:

Her past is rearranged by hardening arteries,

The neighbors’ dogs, ruining her flower bed,

Nieces’ abortions, failing profits, and the dead, of course,

Their nerveless eyes along the wall. They were well fed,

Expiring quietly among the parlor furniture or in some room

Upstairs, the older ones; two of them shot

In wars abroad; one of the girls

Stabbed herself with a paperknife; but gently;

The wound healed.

More sneaky violence, the deaths and injuries alluded to offhandedly, a knowledge the narrator withholds until it happens to come up. (Also interesting here is the callback to the death discovered upstairs in “The Upstairs Room.”) The air of mystery and intrigue is enhanced by the poem’s refusal to provide a narrative of action or exchange, a way out. The eyes of her dead ancestors are locked onto Elizabeth, trapped in her prison of one-sided conversations with people who are no longer around.

It is easy to interpret some of the poetic characters as alter egos. “The frightened male librarian, / Young, though no longer so very young, / Exhibiting signs of incipient baldness, / Gyrated most considerately / Through all the latest books,” reads the beginning of “The Situation Clarified,” with the line likely alluding to the author, who worked as a librarian after graduating with a degree in library science at the University of Denver. If we take this character to be Kees at a younger age, then the poet uses the poem as a lens to consider his younger self as a character and the poem a judgment on himself. We see him operating, gyrating, through this environment in which he is apparently “frightened,” considered as a puppet (“was hung / By wires, pulled from rafters”), caught in a morass of book stacks and local nonprofit politics, the focus of an affair “hushed up more or less immediately” by “an anonymous friend of the Carnegie family.” We are given no specific details on the affair, nor explanations for anyone’s actions. Doing so would make the scene less interesting. Instead, the coyness and assuredness of the language, almost a kind of narrative voiceover (“And thus / Justice triumphed in the end”) imbues the scene with a sense of winky understanding; we can bring our knowledge of how such arrangements proceed to the poem to fill in the rest.

Most notable among these character-centered poems are the four for which Kees seems to be best known, a series centering an elusive, mysterious man-about-town called Robinson. Written across a span of six years (1944–1949), the four poems—“Robinson,” “Aspects of Robinson,” “Robinson at Home” and “Relating to Robinson”— manage to sculpt a character of greater intrigue than those who populate Kees’s fiction. In “Aspects of Robinson,” he writes:

Robinson on a roof above the Heights; the boats

Mourn like the lost. Water is slate, far down.

Through sounds of ice cubes dropped in glass, an osteopath,

Dressed for the links, describes an old Intourist tour.

—Here’s where old Gibbons jumped from, Robinson.

Robinson, of course, shares his name with one of literature’s most famous castaways, and is presented here as a man of the middle twentieth century similarly cast adrift, lonesome in the midst of urban activity that outraces him. As in the aforementioned poems, Robinson does not participate in any conversation, and the isolated spoken lines jump out as warnings, pieces of aural information that disrupt the visual. Through the eyes of this character, boats seen from above “mourn like the lost”; we also learn of yet another suicide, that of a person we haven’t met—an almost needless bit of information that delivers an unexpected trauma. Later, we find “Robinson afraid, drunk, sobbing Robinson / In bed with a Mrs. Morse”—the name repeated as a clock bell tolling, pegging the internal rhyme with “sobbing.” Loneliness and despair run through these poems in a way that almost feels too obvious to Kees’s brand; even the author’s cat was named Lonesome.

An anecdote in Vanished Act: The Life and Art of Weldon Kees by James Reidel (2003), the only comprehensive biography of Kees ever published, has Kees writing to a former supervisor, Norris Getty, following the unceremonious rejection of Kees’s novel, Fall Quarter, with a wail of exasperation familiar to any struggling writer: “I just feel as though I’d told my favorite joke and nobody even smiled.” The quote falls in line with a pattern that seems apparent in both Kees’s art and his career trajectory: an existential dread at the idea of being middling—or worse, being bored—as one more suit-clad body moving around in a land that continually delivers the false promise of exceptionalism. It may also explain the heavy presence of movie-going in his poems. The memory poem “1926” speaks of being twelve years old and coming back “from seeing Milton Sills and Doris Kenyon” to a waiting porch light. A poem called “White Collar Ballad” surveys the options of the middle-class dreamer: “There are lots of places to go:/ Guaranteed headaches at every club, / Plush-and-golden cinemas that always show / How cunningly the heroine and hero rub.” Kees grew up in the Golden Age of Hollywood, a young teenager when the first talking pictures were released. Movies, it might be hypothesized, achieved something in their grandness at capturing and projecting images—even mundane ones—that Kees wished for himself in his art. His poems do the work of centering lonely, aching figures who call out and are desperate to hear an answer.