“Unfortunately, the Book Continues to Be Relevant”: An Interview with Erika Meitner

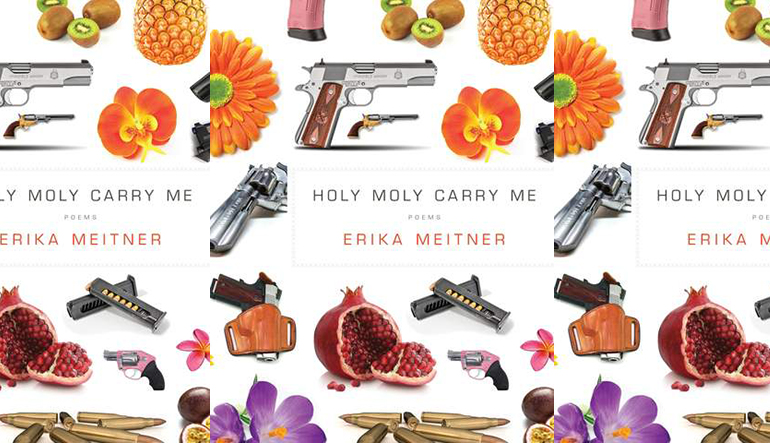

When Erika Meitner was in the process of adopting her youngest son, she was surprised to discover just how many households in her neighborhood had firearms. In her new poetry collection, Holy Moly Carry Me (BOA Editions, 2018), Meitner uses these two life events to examine safety, violence, and raising a family in rural Appalachia. Holy Moly Carry Me administers a searing perspective on Western culture at the same time as it offers a literary salve on our cultural wounds. We met in her office in the Virginia Tech English Department, where Erika is Associate Professor and the Director of the MFA Program in Creative Writing, and discussed the creation of Holy Moly Carry Me, and the poems within.

Annie Raab: Tell me a little bit about how this collection formed and what inspired you to tackle these themes in your poetry.

Erika Meitner: Two big things inspired me to write the poems in Holy Moly Carry Me: the Sandy Hook shootings in Newtown, and the process of adopting my second son. One of the things that kept happening during our home study process—which is actually in one of the poems—was every time our social worker from the adoption agency called before she was going to visit, she’d say, “Make sure your firearms are locked up before I come over.” Every time she said that, my partner and I were like, “Who has firearms?” As we started talking to our neighbors, it turned out a lot of them own firearms. That realization was something anathema for us. My partner and I grew up not knowing people who had firearms in their homes, unless maybe their dad was a cop. [Then,] before our son went over to neighbors’ houses to play, we’d have to have these awkward but intimate conversations with them, asking, “Do you have firearms in your home? Can I see where you keep them? Are they locked up?” Every few weeks we have conversations with our sons about what to do if their friends want to show them guns in their house.

This theme also came out of my first job at Virginia Tech, which started right after the shootings. I signed my contract on a Friday, and the shootings happened the following Monday, April 16th. When I showed up that fall, everyone was traumatized, particularly because the student had been a major in our department and studied with our faculty. This all became one big thread running through Holy Moly Carry Me: gun culture in Appalachia.

AR: Given these heavy experiences and personal connection to tragedy, what do you think was the most difficult poem to write in this collection?

EM: I think “Threat Assessment” was quite difficult to write. First, I had trouble figuring out the body and shape of the poem. I relineated the whole thing eighty to one-hundred times until it came out long and skinny. Then I had to decide on the trajectory of the poem because there’s so much in it. “Threat Assessment” is about race, parenting, gun violence, masculinity, and the American prison system.

AR: Yeah, “Threat Assessment” felt like you really connected contemporary and generational tragedy together. I’m interested in how you address what danger means across generations, especially between people who have survived tragedy.

EM: I think one of the interesting things about my personal history, as the granddaughter of Holocaust survivors, is how my lived experience differs from my family’s. My mother was born in a refugee camp right after my grandparents survived Auschwitz. My father’s family fled to what was then British Mandate Palestine and is now Israel. My grandfather’s entire family went to Theresienstadt and was later wiped out in Auschwitz, so my parents’ lived experience growing up was with traumatized parents in difficult circumstances. I was raised by hyper-vigilant parents who viewed the world in terms of “everybody is out to get you,” which was true to their lived experience. But that wasn’t true to my lived experience as a first-generation American, so I tried not to move through the world that way. It is a constant battle to stay open to the world when you were raised to believe you need to protect yourself from the world.

“Threat Assessment” is also about my experience as a parent. One of the things that became clear to me early on—but is emphasized again with each mass shooting—is that right now, in America, it is very hard to protect our children. And now, as someone who is the parent of an African-American son, that hypervigilance I was raised with actually feels correct in this situation. The truth is, if you move through America in the twenty-first century in a black, masculine body, many people are out to get you. That training instilled by my parents is something I’ve had to draw on as a parent. A lot of the poems speak to the question: how do we protect ourselves and our children when the world is a really violent place, and also stay open to the world?

AR: I noticed in the book the tone shifts from not wanting to be on guard all the time, to empathizing with people in the world who may be pariahs. But when you’re talking about adopting your son, there’s this new fear to educate and protect. This goes beyond protecting kids from school shootings, because for him violence could also happen going about daily life.

EM: One of the complicated things about parenting two children of different races is watching my older son develop the realization of white privilege—the realization that he is safe, but his brother isn’t. I remember one of the most heartbreaking conversations I’ve had with my older son. We were listening to NPR in the car in the Food Lion parking lot when the jury decided to acquit the cops in the Ferguson case. My oldest son turned out to be listening—to be understanding even though he was very young. He said from the backseat, “We can’t ever let my brother go to Missouri.”

At that point, I knew he could not recognize structural racism. He thought racism was locational. I had this moment where I couldn’t speak for a minute, because I didn’t have the heart to tell him his brother isn’t safe anywhere. I had those really difficult conversations with my kids a lot while writing these poems, and sometimes those conversations informed the poetry indirectly.

AR: Do you feel like the way you discuss this with your family is through the lens of “everyday life,” or do you try to frame these topics in a more global perspective?

EM: The thing about having kids is you don’t get to have those conversations when you want to have them. You have them when they want to have them. And it’s always when you’re caught off-guard and always in the daily realm because, with kids, there is no other realm. That’s part of the weird artifice of poetry. One of the things I’ve tried not to do in my work is iron out pop culture, daily consumerism, and domestic living. Often, in poetry, there’s this idea that difficult conversations and epiphanies happen on top of a mountain—somewhere other than in our car in a parking lot. I’m literally at the supermarket every day. Just for probability’s sake, chances are if something happens, it happens in my car in a strip mall parking lot.

AR: Sometimes the narrator seems irreverent or exasperated, but in other poems there’s a sense of relief when kids bring up violence or hostility in common places. How do you decide the tone of these poems?

EM: Tone isn’t something I do consciously. Part of my family’s coping mechanisms for dealing with trauma is humor. My grandmother who survived Auschwitz had a very black sense of humor. That’s a very Jewish thing too, so I feel like in some of the more serious poems, I like to turn it around so there’s a release valve to balance heavy and light together.

AR: “Too Strong” and “Post-Game-Day Blessing” both do a lot of that.

EM: In “Post-Game-Day Blessing,” all of the objects in the poem are all things I actually saw on our walk in town after a game day. It’s always crazy the day after a game, but when you’re walking with first graders, things that are really risqué are all over the place. You’re like “Oh God, I hope no one asks about the condom wrappers!”

AR: Is there anything strange or surprising about living in a rural college town that inspires you?

EM: My academic training outside of literature is in Anthropology in Religion. I studied material culture and ritual studies for almost thirteen years before I dropped out of my doctoral program. Much of it was field work—studying what people do, what gives meaning to their lives, and how their customs define how they live. I grew up in a very Jewish and ethnic place in New York. It was complicated to move to a predominately white “American” place where most people are not immigrants or anything other than evangelical. It made me curious about my neighbors and the ways they live. To some extent, this book is an anthropological experiment as I try to understand my neighbors. This is also one of the safest places I’ve ever lived. It’s sort of an anthropological study to find out why my neighbors own guns for protection but never lock their front doors. I feel like this is the political question we’re asking right now: how do our neighbors live and what exactly does it mean to love your neighbor as yourself?

A lot of the writing in the book was an attempt to understand this alien culture, even though this is a dominant American culture. Originally, this project going to be a photo-text project about gun shows. I ended up going to gun shows at the Civic Center with a photographer, but that never made it into the book because you can’t really take notes at a gun show. I was trying to figure out why people in this area feel threatened. That was a complicated thing for me to face. We are all connected to people by proximity who we may not consider “our people.” As someone who’s never really been a minority—as a New York Jew—I never felt minoritized in the way I do here. How do you interact as a minority, and how does that color your perception of the world?

AR: Did you feel like this awareness was heightened after the 2016 election or did you always feel hyper aware since moving here?

EM: It was definitely heightened after the election. But books take a while to go to print. The vast majority of this book was written well before the election. I wrote the last poem in the book right around the inauguration, but most of the book was finished before the election. While I was working on these gun poems, I was like “I’m so glad this book will be obsolete when it’s published.”

But then the Orlando nightclub shootings happened while I was completing final edits on the book. It turns out this is always going to be relevant until we decide to solve the mass shooting problem. We know how to solve that problem—gun control—but as a country we have not willfully decided to solve this problem. So, unfortunately, the book continues to be relevant.

This piece was originally published on January 9, 2019.