Introduction

Just one of the many delights of putting together this issue of

Ploughshares had to do with the sense of discovery I experienced as I came upon submission after submission which challenged, and changed, my notion of the world.

However familiar I might have been with the work of my colleagues in Princeton University’s creative writing program — on whom, despite the serious risk of being charged with nepotism, I called for papers — I was unprepared for the range and restlessness they continue to bring to making sense of themselves in the world, sometimes in genres with which they’re not primarily associated. I think particularly of the short story by Russell Banks, the extract from a novel by his fellow professor emeritus, Edmund Keeley, of Toni Morrison’s song lyrics, of Joyce Carol Oates’s short play, of the selection of stunning aphorisms by James Richardson, of the poem by A. J. Verdelle.

Add to all of this spectacular new prose fiction from Lan Samantha Chang, James Lasdun, Lynne Tillman, and Edmund White, poems by Mary Jo Bang, Yusef Komunyakaa, Laurie Sheck, Renée and Theodore Weiss, Susan Wheeler, and C. K. Williams, translations of Quasimodo by Jonathan Galassi, and one has some little sense of the vibrancy of the program with which they’ve all been associated in the academic year 1999-2000, a year in which we celebrated the sixtieth anniversary of its founding in 1939.

Also associated with the Princeton creative writing program are two recent students of mine, Troy Jollimore and Emily Moore, whose work I’m delighted to be able to bring to a wider audience. Another two of my ex-students find their way in here, Cathy Bowman of Columbia University School of the Arts, where I taught briefly some years ago, and Meredith Drum of the Bread Loaf School of English, where I’ve taught for the last few summers.

I have to confess that I wasn’t quite sure what to expect of the unsolicited work on which I drew for the other fifty percent of this edition of

Ploughshares, since there’s always the chance that the season might not be a good one. So it was with relief that, yet again, I found so much work of such remarkable vigor and variousness.

Despite that variousness, one may point to at least one widespread trait in both the prose fiction and poetry included here. It is an increasing tendency to synthesize the traditional and the torn, the formal and the fractured, in ways that no longer seem gimmicky but absolutely germane to the business of what I referred to earlier on — writers “making sense of themselves” in a world at once traditional and torn, formal and fractured.

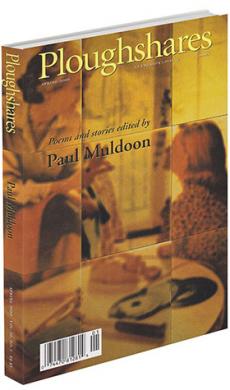

That synthesis of the familial and the fissured, neatly encapsulated in the cover image by Mary Behrens, is one in which I hope you, too, will find “a momentary stay against confusion.”