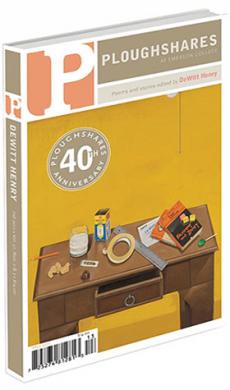

Introduction

For this fortieth anniversary issue, I invited former guest editors to contribute new work of their own, to nominate and introduce an emerging writer, or to give an account of turning points in their careers. Among the twenty-five who responded, I include here fiction writers, nonfiction writers, and poets. Longtime Ploughshares readers will recognize the joining of their talents as a reunion. To readers new to Ploughshares, they offer a variety of subjects, forms, and styles, as well as a collective conviction in the possibilities of literature.

Howard Norman, Sue Miller, Ellen Wilbur, and Don Lee actually first published fiction in Ploughshares; then each went on to edit and guest-edit issues and to nurture promise in others as they themselves grew in their careers. Joyce Peseroff ’s early poems appeared in our second issue; she later served as managing editor, as a guest editor, and as editor of The Ploughshares Poetry Reader. Here she joins Elizabeth Spires and Ellen Bryant Voigt in introducing new poets. Here also Dan Wakefield introduces an astonishing nonfiction narrative by Susan Falco; and James Alan McPherson, Don Lee, and Margot Livesey introduce new fiction writers Laura van den Berg, Nickolas Butler, and James Scott.

For three generations our intention has been to make “a distinct contribution to the national adventure in writing” (as Gordon Lish once praised our founding generation); and to “convey the bright hope” of contemporary writing (as Ted Solotaroff put it).

Of course, not everyone regards literary publishing as an adventure. Shortly after our first issue appeared, the influential critic John W. Aldridge saw literary magazines as superfluous, if not culturally destructive. In “Literary Magazines and the Great Gray Middle” (1972), he argued that the wave of new titles—including Ploughshares (1971), American Poetry Review (1972), Antaeus (1972), Parnassus (1972), Yardbird Reader (1972), Fiction (1972), Iowa Review (1970), Salmagundi (1965), Field (1969), and even American Review (1967)—promised at best only “mediocrity.” From once introducing the Modernist masters, literary magazines had declined to serving as an institutionalized outlet for a “new fabricated literary mass culture [with] great numbers of interchangeable minor and major and major-minor talents, literary engineers, pitchmen, and writers whose profession is not writing but being writers.” Contemporary writing, as Aldridge judged it, reflected but failed to transform the realities of our time with “the serenity of understanding.”

Ploughshares challenged this sort of august diffidence. On our side of the gap between the World War II and Vietnam War generations, we saw literature flourish. As I wrote in a review of The Little Magazine in America: A Modern Documentary History (TriQuarterly, 1978): “The question is less one of providing sanctuary for an avant-garde than it is of providing adequate access and recognition for a whole new generation of writers remarkable for their diversity of directions, and of posing standards of taste deeper than direction itself.”

Our guest-editor system was intended to explore and to advocate for differences by creating “contexts of appreciation.” Worthwhile writers, we believed (along with Wordsworth and Coleridge in Lyrical Ballads), needed to create the taste by which they would be appreciated, and each of our issues would offer a different writer that opportunity as an editor. Given our cofounder Peter O’Malley from Dublin and our early sponsorship by his and his partners’ pub in Cambridge, The Plough and the Stars, we were also inspired by Yeats’ Irish Revival and by the tradition of literary pubs publishing broadsides for their patrons.

Miraculously, thanks to the good will, sacrifice, and generosity of many hands, the magazine and its idea persisted and grew. We became regarded for editorial “prescience,” as we consistently discovered writers who persisted and grew.

Bruce Bennett was one of the founding editors. Lloyd Schwartz joined Robert Pinsky and Frank Bidart in editing a landmark issue in 1975, then edited solo in 1979. Gail Mazur’s early poem “Baseball” appeared in 1977; she then became a regular contributor and edited issues in 1980 and 1983, with our first four-color covers of paintings by her husband Michael Mazur. Jay Neugeboren appeared with a story in 1978 and then edited the issue in which Sue Miller first appeared. Alan Williamson and Richard Tillinghast also edited issues in the early 1980s.

Poet Jennifer Rose (presented here with an excerpt from her memoir) succeeded Joyce Peseroff and Susannah Lee as managing editors, and was herself succeeded by Don Lee, as we negotiated an affiliation with Emerson College in 1988. In 1992, Don succeeded me as editor-in-chief, and for the next fifteen years under his leadership, we expanded our grant support, had more appearances in the annual prize anthologies than any other magazine, tripled our circulation, expanded our network from regional to national to international, and entered the digital age. Marilyn Hacker, Maxine Kumin, Gary Soto, Jane Hirshfield, Elizabeth Spires, Margot Livesey, B. H. Fairchild, and Alice Hoffman all edited issues under his tenure. When he left in 2007, John Skoyles and Margot Livesey joined me as interim staff, and we were successful in recruiting Ladette Randolph as the new editor-inchief. Now Ladette is leading Ploughshares to new generations.

What a privilege it is to return as a guest editor myself for this occasion, guest to an institution that remains young, necessary to our literary life, and growing. And how wonderful to present this roster of writers who do, individually and collectively, transform the realities of our times.