rev. of The Thing Itself by Richard Todd

The Thing Itself: On the Search for Authenticity, by Richard Todd (Riverhead): Along with his witty and astute social commentary on objects, places, politics, words, and ideas, all of which serve to foreground his sensibility, Richard Todd offers us fragmentary revelations of his personal life. Gradually these revelations deepen into a fully realized, brave, and movingly honest memoir (part confession, part portrait of the artist, part pilgrimage of soul). Of course, Todd is quick to remind us that "all memoir is at its heart fictive."

Todd’s life spans a Forties childhood (with a father in the Navy), a Fifties adolescence in Darien, Connecticut, a Sixties college education at Amherst, first work in Manhattan, basic training in the Army, graduate school, marriage, parenting three daughters, and a life-long career in letters in Boston as an editor of The Atlantic Monthly and later as a signature editor at Houghton Mifflin.

The book opens with Todd at mid-life, aspiring to be a country gentleman. While his editing career is urban, he tries farming as an avocation. He loves antiques. He prides himself on an old tractor, made in 1948. He sets out to restore an 18th century house. He verges on the cantankerous in his humor for "the authentic," even disdaining a famous guest for wearing a tee shirt emblazoned with a trade name. Before long, he admits to much of this as folly; his barn becomes a "Museum of Lost Enthusiasms." There is a bucket for sheep they once raised: "but after a couple of seasons we lost too many lambs and I lost the will to care for them." There are tractor chains, which once "a young guy who was in love with a daughter of mine" help put on. "I never let him know how much I appreciated it."

There are intervening meditations on reproductions of great art, and on art forgeries; and then on tourism in search of the "real" place; and then Todd returns to the idea of "the country…as a repository of purity, of tradition, of simplicity" and contrasts that idea to that of the suburb, which in turn introduces us again to his background: "Born in the country, I nevertheless had a mostly suburban childhood" and the origins of his class consciousness. Before his parents’ move to Darien, he confides, "I had lived in a dream world of homogeneity on ‘the farm’ and in an unpretentious suburb. But it did not take long to realize that the new landscape had a logical organization, and the organizing principle was money." He became ashamed of his parents’ "little house" and envied the rich. Later he learned to see suburban pretensions "as something very unsatisfactory indeed." Hence in mid-life his return to the country, where "I fell immediately into the romantic notion that people of the land are better people, and I idolized my farming neighbors and apprenticed myself to them." Of course, he becomes his own Touchstone: "I was terrible at it. It was a wonder that my young family did not contract a fatal disease from the unsanitary conditions." But after an interlude back in the city, he tries again, "with more land and fewer chores," and prizes the rural landscape because "its patterns stand apart from conventional social hierarchies."

In the last section of the book, Todd turns to consider "that most vexed of subjects, the self." We have had earlier glimpses of conflict. In a chapter about the idea of the wilderness, he tells us: "new and hastily married, still in graduate school, penniless, without a plan," he feared the future, but somehow hiking with his wife in the Sierras, felt "relocated in the world." Now he confesses to "merry" flirting in his thirties, and perhaps worse: "I have done worse than make overtures to that pretty, gray-eyed woman."

Though suspicious of fashionable memoirs and their claims, Todd is haunted by memories of shame. "From nowhere they come, and I wince or even mutter aloud to drive away these memories, some of them from forty or more years back." He remembers being caught as a child thief by his parents. He remembers emblematic incidents of cowardice: "being too scared to get into a sailboat I didn’t know how to sail yet"; "the cowardice that endures is that hesitation that prevents me from the gesture or the sentence that puts the self at risk, but might free it too."

He recognizes and admits with clarity, finally, that he harbors many selves; some contemptible, some generous. He thinks of "an infinity of fraudulent moments: the false laugh, the swallowed opinion, the sycophant’s praise—or worse, the bullying of certitude, the unguent of willed charm. Company courtier, cultural bureaucrat, hedger of true feelings." He has been both sentimental and hard of heart. He has taken refuge in books, and in words. He’s had a drinking problem. "I have fled, and do flee from pain that might have been instructive," he admits. He has been "drunk on words, drunk on class, or merely drunk," but still "there is a fellow I keep beckoning back. He is hard to name, but is occasionally capable of self-forgiveness. He sees the world not in a hierarchy of status but of virtue…he somehow makes people closest to him understand that he loves them." While Todd is fully implicated in the culture he criticizes, in the vigilance of his mind, heart, and prose, there is this redemption. "Love often delivers," he says of his long marriage and parenting. He makes a figure in which to contemplate ourselves. —DeWitt Henry

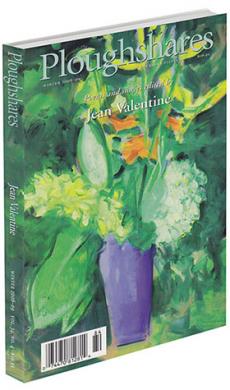

DeWitt Henry is the founding editor of Ploughshares. His latest book is Safe Suicide: Narratives, Essays, and Meditations.