The Mind Afoot: rev. of Descending Figure by Louise Glück

Much contemporary poetry attempts to charge a landscape with the imaginative self through an allegorical and mythological vision. While poetry of the past tends to place the self in a landscape where it perceives and reacts, our contemporaries frankly reverse the process and locate the landscape in the psyche. This extends what Roy Harvey Pearce has described as the Adamic vision of American poetry; but the tone now is detached and otherworldly, touched by Surrealism. The old dualism of the I and the Not-I remains unresolved; but however obsessed with that Romantic dilemma, our younger poets anchor both elements in the myth-making imagination, as Jung replaces Christ as the cartographer of the unregenerate soul.

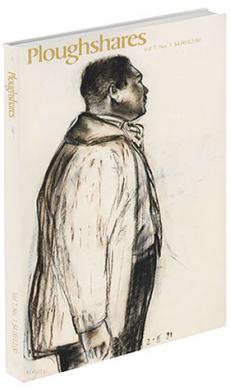

Louise Glück's poems remind us that mythmaking is closely related to allegory even when the "thing itself" retains its integrity. The most ambitious poem in her new book (

Descending Figure, Ecco Press, $9.95) is a sequence entitled "The Garden." It makes models both of a mind and a culture, and renews an old myth through an imitation of the creative process itself. Glück's bleak imagery presents a set of possibilities that voice and metaphor resolve into a gray and Barbizon-like merging of self and landscape. The first part of the sequence is a complex restatement of Genesis:

. . .the hiss and whirr

of houses gliding into their places.

And the wind

leafs through the bodies of animals.

The sequence ends with a poem entitled "The Fear of Burial": "the body waits to be claimed./The spirit sits beside it, on a small rock." This is a rich metaphor of the history and failure of Christian dualism, which ties the Romantic and modern existential angst to the ages. The poem then ends with a metaphor that aptly mythologizes the necessities of physical life and evokes once again the failure of the Christian ideal of redemption through virtue and austerity.

How far away they seem,

the wooden doors, the bread and milk

laid like weights on the table.

The sequence is a miracle of compression, a tight allegory composed of complex metaphors that evoke both the Biblical creation myth and the modern myth of self-creation. It is a "model of the mind" in that it replicates the overlays of association with which the mind works; yet is aesthetically uncompromising in its reliance on straightforward imagery. It is a poem that reminds us that "no ideas but in things" does not mean "no ideas," but is a challenge for us to discover resonances of the physical world in secret rooms of the psyche.

Glück has found these rooms to be filled with language, as a monk's secret rooms might be filled with God. Poetry is not religion, but it is salvation, sometimes:

The word

is

bear: you give and give, you empty

yourself into a child. And you survive

the automatic loss.

("Autumnal")

Glück's aesthetic is grounded in her imaginatively-apprehended landscapes, but her ultimate faith is in the power of the creative mind to resolve the isolation of the self from the external world through language.

This topographical aesthetic contains a certain danger aggravated by the influence of Surrealism. If the poet presents us with a purely imaginative landscape he or she may sentimentally underscore the isolation of the individual, and trigger the bathos of solipsism that Wallace Stevens took such trouble to avoid. Rather, we need redeemed landscapes, in which the imaginative self is a concrete presence that infuses our vision of our culture with a viable symbolic content. Allegory, the model of the mind, is not here a set of simple signs: it is the affirmation that the poet and the reader might understand the world through this exploration of the self and language. Resorting to evocation instead of infusion leaves us with imaginary gardens inhabited only by imaginary toads.