rev. of Out West by Fred Leebron

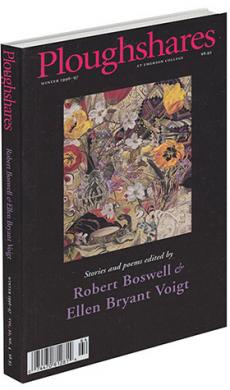

Out West

A novel by Fred G. Leebron. Doubleday, $21.95 cloth. Reviewed by Don Lee.

There is nothing timid about Fred G. Leebron’s first novel,

Out West. He takes two basically decent, highly educated, young social do-gooders and quickly steeps them into the squalid heart of two murders, and then asks us, his readers, to side with the couple. That we mostly do is evidence of Leebron’s remarkable talents as a writer.

Of course, Benjamin West and Amber Keenan, both around thirty, are not exactly irreproachable to begin with. Benjamin worked for ten years at an institute for handicapped children, but he never fulfilled his promising academic career, never even mailed out his applications for Ph.D. programs. Instead, he got caught with two ounces of marijuana and a seventeen-year-old girl. After a six-month prison term, he drives cross-country from Pennsylvania to San Francisco, looking for a fresh start. Not much is waiting for him there. A dead-end, minimum-wage job as a desk clerk at a seedy residential hotel in the Tenderloin. But he views this new station, as he sits in the hotel lobby behind a grillwork of bars, as proper penance: “It was, indisputably, a kind of cell. He liked it.”

Likewise, Amber, a VISTA worker who is staying in the hotel, is trapped in contrition. Three months before, she had tried to kill her rich, indolent boyfriend, Dean, whom she had lived with in Los Angeles for three years. A poet teaching part-time at a college, he slept with a fellow teacher, then cruelly flaunted the affair in Amber’s face. Amber, numb, temporarily demented, opened up the oven vents in his apartment, hoping Dean would ignite the gas when he lit a cigarette. Yet his new lover, not Dean, was killed, and Amber is now unable to sleep: “she had drawn a line between herself and a place — the place of innocence and simplicity, or at least the place of indifferent interaction with humanity — and while it was overwrought and self-pitying to think of it like this, it was true. She had killed someone. . . . She was guilty.”

A day after his arrival, Benjamin and Amber have sex, and while he is immediately taken by her, she has misgivings. She is ready to break it off, when Dean arrives and attacks her in her hotel room. Benjamin intercedes and in self-defense kills him. With their past deeds, they can hardly go to the police, and they are now, however reluctantly, bound to each other. What follows is a road nightmare, ripe with dark humor, as they drive first around San Francisco and then to L.A., trying to dump Dean’s decomposing body and cover their tracks. Leebron’s prose is lucid and evocative throughout the novel, and he seamlessly shifts between Benjamin and Amber’s points of view. He is especially adept at describing the particulars of these California cities, the misery of the Tenderloin, the surreal beauty of the highway landscapes, the prefab constructs of convenience stores, gas stations, and fast-food restaurants that substitute as architecture. Granted, this novel is not for everyone. The scenes can become

gruesome, fetid, and at times, there are lapses in credibility, gaps in background and explication. Yet

Out West progresses with tremendous momentum, rushing through a harrowing week in these characters’ lives, and with great skill, Leebron creates a rarity: an original, provocative, literary page-turner.